Plotinus

[1][2][3][4] Historians of the 19th century invented the term "neoplatonism"[3] and applied it to refer to Plotinus and his philosophy, which was vastly influential during late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance.

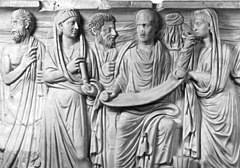

[13][14] Plotinus had an inherent distrust of materiality (an attitude common to Platonism), holding to the view that phenomena were a poor image or mimicry (mimesis) of something "higher and intelligible" (VI.I) which was the "truer part of genuine Being".

This distrust extended to the body, including his own; it is reported by Porphyry that at one point he refused to have his portrait painted, presumably for much the same reasons of dislike.

[2][3][4] Upon hearing Ammonius' lecture, Plotinus declared to his friend: "this is the man I was looking for",[2] began to study intently under his new instructor, and remained with him as his student for eleven years.

[2][17] In the pursuit of this endeavor he left Alexandria and joined the army of the Roman emperor Gordian III as it marched on Persia (242–243).

His innermost circle included Porphyry, Amelius Gentilianus of Tuscany, the Senator Castricius Firmus, and Eustochius of Alexandria, a doctor who devoted himself to learning from Plotinus and attending to him until his death.

Other students included: Zethos, an Arab by ancestry who died before Plotinus, leaving him a legacy and some land; Zoticus, a critic and poet; Paulinus, a doctor of Scythopolis; and Serapion from Alexandria.

At one point Plotinus attempted to interest Gallienus in rebuilding an abandoned settlement in Campania, known as the 'City of Philosophers', where the inhabitants would live under the constitution set out in Plato's Laws.

"[19] Eustochius records that a snake crept under the bed where Plotinus lay, and slipped away through a hole in the wall; at the same moment the philosopher died.

Plotinus was unable to revise his own work due to his poor eyesight, yet his writings required extensive editing, according to Porphyry: his master's handwriting was atrocious, he did not properly separate his words, and he cared little for niceties of spelling.

Plotinus intensely disliked the editorial process, and turned the task to Porphyry, who polished and edited them into their modern form.

[22] The first emanation is Nous (Divine Mind, Logos, Order, Thought, Reason), identified metaphorically with the Demiurge in Plato's Timaeus.

(I.6.6 and I.6.9) The essentially devotional nature of Plotinus' philosophy may be further illustrated by his concept of attaining ecstatic union with the One (henosis).

[23] The philosophy of Plotinus has always exerted a peculiar fascination upon those whose discontent with things as they are has led them to seek the realities behind what they took to be merely the appearances of the sense.

In Platonism, and especially neoplatonism, the goal of henosis is union with what is fundamental in reality: the One (τὸ Ἕν), the Source, or Monad.

[27] Henosis for Plotinus was defined in his works as a reversing of the ontological process of consciousness via meditation (in the Western mind to uncontemplate) toward no thought (Nous or demiurge) and no division (dyad) within the individual (being).

In a 1929 essay, E. R. Dodds showed that key conceptions of neoplatonism could be traced from their origin in Plato's dialogues, through his immediate followers (e.g., Speusippus) and the neopythagoreans, to Plotinus and the neoplatonists.

'[30] Further research reinforced this view and by 1954 Merlan could say 'The present tendency is toward bridging rather than widening the gap separating Platonism from neoplatonism.

According to A. H. Armstrong, Plotinus and the neoplatonists viewed Gnosticism[clarification needed] as a form of heresy or sectarianism to the Pythagorean and Platonic philosophy of the Mediterranean and Middle East.

[note 2] Also according to Armstrong, Plotinus accused them of using senseless jargon and being overly dramatic and insolent in their distortion of Plato's ontology.

[note 6] Armstrong believed that Plotinus also attacks them as elitist and blasphemous to Plato for the Gnostics despising the material world and its maker.

Some of these are directed at very specific tenets of Gnosticism, e.g. the introduction of a ‘new earth’ or a principle of ‘Wisdom’, but the general thrust of this treatise has a much broader scope.

However, Plotinus attempted to clarify how the philosophers of the academy had not arrived at the same conclusions (such as misotheism or dystheism of the creator God as an answer to the problem of evil[36]) as the targets of his criticism.

", Plotinus makes the argument that specific stars influencing one's fortune (a common Hellenistic theme) attributes irrationality to a perfect universe, and invites moral depravity.

Plotinian concepts have been discussed in a cinematic context and relate Plotinus' theory of time as a transitory intelligible movement of the soul to Bergson’s and Deleuze’s time-image.

As with Islam and Christianity, apophatic theology and the privative nature of evil are two prominent themes that such thinkers picked up from either Plotinus or his successors.

In the Renaissance the philosopher Marsilio Ficino set up an Academy under the patronage of Cosimo de Medici in Florence, mirroring that of Plato.

In Great Britain, Plotinus was the cardinal influence on the 17th-century school of the Cambridge Platonists, and on numerous writers from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to W. B. Yeats and Kathleen Raine.

[47][48][49][50] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Ananda Coomaraswamy used the writing of Plotinus in their own texts as a superlative elaboration upon Indian monism, specifically Upanishadic and Advaita Vedantic thought.

"[52] Advaita Vedanta and neoplatonism have been compared by J. F. Staal,[53] Frederick Copleston,[54] Aldo Magris and Mario Piantelli,[55] Radhakrishnan,[56] Gwen Griffith-Dickson,[57] and John Y.