Plum pudding model

Based on experimental studies of alpha particle scattering (in the gold foil experiment), Ernest Rutherford developed an alternative model for the atom featuring a compact nucleus where the positive charge is concentrated.

The analogy is perhaps misleading because Thomson likened the positive sphere to a liquid rather than a solid since he thought the electrons moved around in it.

Thomson hypothesized that the quantity, arrangement, and motions of electrons in the atom could explain its physical and chemical properties, such as emission spectra, valencies, reactivity, and ionization.

Heavier and slower than beta particles, these were the key tool used by Rutherford to find evidence against Thomson's model.

Part of the attraction of the vortex model was its possible role in describing the spectral data as vibrational responses to electromagnetic radiation.

Thomson's model was the first to assign a specific inner structure to an atom,[9]: 9 though his earliest descriptions did not include mathematical formulas.

Thomson attempted unsuccessfully to reshape his model to account for some of the major spectral lines experimentally known for several elements.

[12] In 1899 Thomson reiterated his atomic model in a paper that showed that negative electricity created by ultraviolet light landing on a metal (known now as the photoelectric effect) has the same mass-to-charge ratio as cathode rays; then he applied his previous method for determining the charge on ions to the negative electric particles created by ultraviolet light.

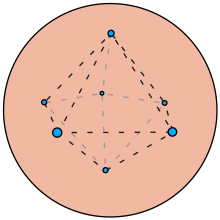

[14] Thomson starts with a short description of his model ... the atoms of the elements consist of a number of negatively electrified corpuscles enclosed in a sphere of uniform positive electrification, ...[14]Primarily focused on the electrons, Thomson adopted the positive sphere from Kelvin's atom model proposed a year earlier.

After discussing his many formulae for stability he turned to analysing patterns in the number of electrons in various concentric rings of stable configurations.

[18] In a lecture delivered to the Royal Institution of Great Britain in 1905,[19] Thomson explained that it was too computationally difficult for him to calculate the movements of large numbers of electrons in the positive sphere, so he proposed a practical experiment.

This involved magnetised pins pushed into cork discs and set afloat in a basin of water.

Before 1906 Thomson considered the atomic weight to be due to the mass of the electrons (which he continued to call "corpuscles").

In 1906 he used three different methods, X-ray scattering, beta ray absorption, or optical properties of gases, to estimate that "number of corpuscles is not greatly different from the atomic weight".

[20][21] This reduced the number of electrons to tens or at most a couple of hundred and that in turn meant that the positive sphere in Thomson's model contained most of the mass of the atom.

This meant that Thomson's mechanical stability work from 1904 and the comparison to the periodic table were no longer valid.

[21]: 269 In 1907, Thomson published The Corpuscular Theory of Matter[22] which reviewed his ideas on the atom's structure and proposed further avenues of research.

He included one important correction: he replaced the beta-particle analysis with one based on the cathode ray experiments of August Becker, giving a result in better agreement with other approaches to the problem.

[21]: 273 Experiments by other scientists in this field had shown that atoms contain far fewer electrons than Thomson previously thought.

[26] Thomson refused to jump to the conclusion that the basic unit of positive charge has a mass equal to that of the hydrogen ion, arguing that scientists first had to know how many electrons an atom contains.

Thomson typically assumed the positive charge in the atom was uniformly distributed throughout its volume, encapsulating the electrons.

Thomson did not explain how this equation was developed, but the historian John L. Heilbron provided an educated guess he called a "straight-line" approximation.

[32] Consider a beta particle passing through the positive sphere with its initial trajectory at a lateral distance b from the centre.

To find the combined effect of the positive charge and the electrons on the beta particle's path, Thomson provided the following equation:

[36] The Thomson models simply could not produce electrostatic forces of sufficient strength to cause such large deflection.

This led Rutherford to discard the Thomson for a new model where the positive charge of the atom is concentrated in a tiny nucleus.

Thomson hypothesised that the arrangement of the electrons in the atom somehow determined the spectral lines of a chemical element.

Niels Bohr and Erwin Schroedinger later incorporated quantum mechanics into the atomic model.

The Thomson problem in mathematics seeks the optimal distribution of equal point charges on the surface of a sphere.

[37][38] The first known writer to compare Thomson's model to a plum pudding was an anonymous reporter in an article for the British pharmaceutical magazine The Chemist and Druggist in August 1906.

Left: Had Thomson's model been correct, all the alpha particles should have passed through the foil with minimal scattering.

Right: What Geiger and Marsden observed was that a small fraction of the alpha particles experienced strong deflection.