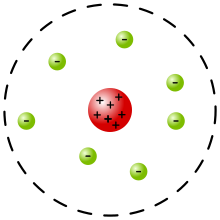

Rutherford model

Rutherford directed the Geiger–Marsden experiment in 1909, which showed much more alpha particle recoil than J. J. Thomson's plum pudding model of the atom could explain.

[1]: 13 Between 1904 and 1910 Thomson developed formulae for the deflection of fast beta particles from his atomic model for comparison to experiment.

Similar work by Rutherford using alpha particles would eventually show Thomson's model could not be correct.

[1]: 35 In a 1901 paper,[3] Jean Baptiste Perrin used Thomson's discovery in a proposed a Solar System like model for atoms, with very strongly charged "positive suns" surrounded by "corpuscles, a kind of small negative planets", where the word "corpuscles" refers to what we now call electrons.

Perrin discussed how this hypothesis might related to important then unexplained phenomena like the photoelectric effect, emission spectra, and radioactivity.

These experiments demonstrated that alpha particles "scattered" or bounced off atoms in ways unlike Thomson's model predicted.

In 1908 and 1910, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in Rutherford's lab showed that alpha particles could occasionally be reflected from gold foils.

[6] In a May 1911 paper,[7] Rutherford presented his own physical model for subatomic structure, as an interpretation for the unexpected experimental results.

Rutherford only committed himself to a small central region of very high positive or negative charge in the atom.

Eventually Bohr incorporated early ideas of quantum mechanics into the model of the atom, allowing prediction of electronic spectra and concepts of chemistry.