Po Valley

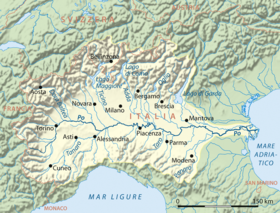

It extends approximately 650 km (400 mi) in an east-west direction, with an area of 46,000 km2 (18,000 square miles) including its Venetic extension not actually related to the Po basin; it runs from the Western Alps to the Adriatic Sea.

The flatlands of Veneto and Friuli are often considered apart since they do not drain into the Po, but they effectively combine into an unbroken plain, making it the largest in Southern Europe.

183/89 to oversee "protection of lands, water rehabilitation, the use and management of hydro resources for the national economic and social development, and protection of related environment" within the Po basin, has authority in several administrative regions of north Italy, including the plain north of the Adriatic and the territory south of the lower Po, as shown in the regional depiction included with this article.

The law defines the Po basin as "the territory from which rainwater or snow and glacier melt flows on the surface, gathers in streams of water either directly or via tributaries...".

After that time due to human alteration of geologic factors, such as the sedimentation rate, the delta has been degrading and the coastline subsiding, resulting in ongoing contemporaneous crises in the city of Venice.

Regardless of whether this concept accurately describes its geology, the valley is manifestly a sediment-filled trough, or virtual syncline, continuous with the deeps of the Adriatic Sea.

[6] The valley is broadly divided into an upper, drier part, often not particularly suited for agriculture, and a lower, very fertile, and well-irrigated section, known in Lombardy and western Emilia as la Bassa, 'the low (plain)'.

So we have the Piedmontese vaude and baragge, the Lombard brughiere and Groane, or, exiting from the Po valley proper, the Friulian magredi, areas remote from easily reachable water tables and covered with dense woods or dry soils.

This specific meaning for 'lower plain' derive from a geologic feature called the fontanili line or zone, a band of springs around the Val Po, heaviest on the north, on the lowermost slopes of the anticline.

Surface runoff water (the Po and its affluents) is not of much value to the valley's dense population for drinking and other immediate uses, being unreliable, often destructive, and heavily polluted by sewage and fertilizers.

According to historical-archaeological data, indeed, the wetlands were exploited for fishing as well as for transport by boat while the early medieval sites settled on the fluvial ridges, in topographically higher and strategic position[13] in the surrounding swampy meadows.

The Po Valley has been completely turned to agriculture since the Middle Ages, when efforts from monastic orders, feudal lords and free communes converged.

Both winter and summer are less mild in the lower parts along the Po, while the Adriatic Sea and the great lakes moderate the local climate in their proximity.

The almost enclosed nature of the Padan basin with much road traffic, makes it prone to a high level of pollution in winter, when cold air clings to the soil.

The natural potential vegetation of the Po basin is a mixed broadleaf forest of pedunculate oak, poplars, European hornbeam, alders, elderberry, elms, willows, maples, ash, and other central-European trees.

Sites such as Monte Poggiolo may have served as refuges of human populations fleeing the terribly cold conditions of Northern Europe during the subsequent glaciations along pleistocene.

[17] Once the long Pax Romana showed signs of weakening, and after enduring the passage of several Germanic invaders, and even that of Attila and his Huns, the Po valley was to found no peace.

The Lombards divided their domain in duchies, often contending for the throne; Turin and Friuli, in the extreme west and east end respectively, seem to have been the most powerful, whereas the capital soon shifted from Verona to Pavia.

Soon Milan became the most powerful city of the central plain of Lombardy proper, and despite being razed in 1162, it was a Milan-driven Lombard League with Papal benediction that defeated emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

Cereals became a more significant constituent in the average diet and in the agrarian regime compared to the centuries before, leading populations to reconfigure the medieval natural landscape for agricultural purposes.

In creating new land for cultivation and settlement, the European communities triggered a massive landscape transformation through woodland clearance, arable intensification, the development of irrigation systems and the drainage of wetlands.

With Venice's expansion on the eastern mainland in the first half of the 15th century and Milan's supremacy in the center and west the region (not significantly diminished by the Black Death of 1348) reached unprecedented peaks of prosperity.

Even Switzerland received some Italian-speaking lands in the north (Canton Ticino, not technically a part of the Padan region), and the Venetian domain was invaded, forcing Venice into neutrality as an independent power.

When Napoleon I entered the Po Valley during some of his brightest campaigns (1796 and 1800, culminating in the historical Battle of Marengo), he found an advanced country and made it into his Kingdom of Italy.

The World Wars did not significantly damage the area, despite the destruction caused by Allied aerial bombing of many cities and heavy frontline fighting in Romagna.

The Resistance protected the main industries, which the Third Reich was using for war production, preventing their destruction: on 25 April 1945 a general insurrection in the wake of the German defeat was a huge success.

Turin and Milan are also at the top of the European ranking—3rd and 5th respectively—in terms of increased mortality from nitrogen dioxide, a gas that is produced mainly from traffic and in particular from diesel vehicles, while Verona, Treviso, Padova, Como and Venice rank eleventh, fourteenth, fifteenth, seventeenth and twenty-third respectively.