Poetry

Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such as assonance, alliteration, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia, rhythm (via metre), and sound symbolism, to produce musical or other artistic effects.

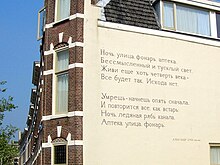

Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter.

Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition,[4] testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.

Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme, and emphasized aesthetics which distinguish poetry from the format of more objectively-informative, academic, or typical writing, which is known as prose.

Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor, simile, and metonymy[8] establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived.

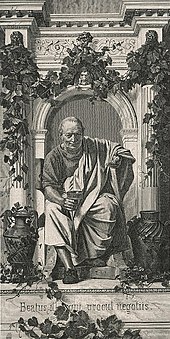

A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse (either classical or contemporary), or through other (often canonised) poets' work which sets some kind of example or challenge.

Thus if, for example, a poem asserts, "I killed my enemy in Reno", it is the speaker, not the poet, who is the killer (unless this "confession" is a form of metaphor which needs to be considered in closer context – via close reading).

[12] The Istanbul tablet#2461, dating to c. 2000 BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem.

[28] Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition to prose, which they generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure.

[31] During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was also substantially more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part due to the spread of European colonialism and the attendant rise in global trade.

Numerous modernist poets have written in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm and tone established by non-metrical means.

[37] Today, throughout the world, poetry often incorporates poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that once made sense within a tradition such as the Western canon.

The literary critic Geoffrey Hartman (1929–2016) used the phrase "the anxiety of demand" to describe the contemporary response to older poetic traditions as "being fearful that the fact no longer has a form",[39] building on a trope introduced by Emerson.

[41] A 2024 study found that AI-generated poems were rated by non-expert readers as more rhythmic, beautiful, and human-like than those written by well-known human authors.

[57] Languages which use vowel length or intonation rather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such as Ottoman Turkish or Vedic, often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.

"[107] Since the rise of Modernism, some poets have opted for a poetic diction that de-emphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting instead the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration of tone.

[109] Allegorical stories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the West during classical times, the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Aesop's Fables, repeatedly rendered in both verse and prose since first being recorded about 500 BCE, are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages.

Among the most common forms of poetry, popular from the Late Middle Ages on, is the sonnet, which by the 13th century had become standardized as fourteen lines following a set rhyme scheme and logical structure.

[131] Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry (which was generally referred to as "waka"), and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes.

This was likely derived from when the Thai language had three tones (as opposed to today's five, a split which occurred during the Ayutthaya Kingdom period), two of which corresponded directly to the aforementioned marks.

The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues.

Hafez uses the ghazal to expose hypocrisy and the pitfalls of worldliness, but also expertly exploits the form to express the divine depths and secular subtleties of love; creating translations that meaningfully capture such complexities of content and form is immensely challenging, but lauded attempts to do so in English include Gertrude Bell's Poems from the Divan of Hafiz[146] and Beloved: 81 poems from Hafez (Bloodaxe Books) whose Preface addresses in detail the problematic nature of translating ghazals and whose versions (according to Fatemeh Keshavarz, Roshan Institute for Persian Studies) preserve "that audacious and multilayered richness one finds in the originals".

It has been speculated that some features that distinguish poetry from prose, such as meter, alliteration and kennings, once served as memory aids for bards who recited traditional tales.

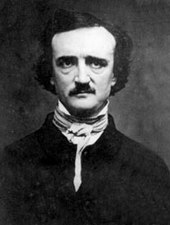

[155] Notable narrative poets have included Ovid, Dante, Juan Ruiz, William Langland, Chaucer, Fernando de Rojas, Luís de Camões, Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, Robert Burns, Adam Mickiewicz, Alexander Pushkin, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Tennyson, and Anne Carson.

[156] Notable poets in this genre include Christine de Pizan, John Donne, Charles Baudelaire, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Antonio Machado, and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

[160] Satirical poets outside England include Poland's Ignacy Krasicki, Azerbaijan's Sabir, Portugal's Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage, and Korea's Kim Kirim, especially noted for his Gisangdo.

[161][162] Notable practitioners of elegiac poetry have included Propertius, Jorge Manrique, Jan Kochanowski, Chidiock Tichborne, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, John Milton, Thomas Gray, Charlotte Smith, William Cullen Bryant, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Evgeny Baratynsky, Alfred Tennyson, Walt Whitman, Antonio Machado, Juan Ramón Jiménez, William Butler Yeats, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Virginia Woolf.

[172] Independently of the European poetic tradition, Sanskrit prose-poetry (gadyakāvya) has existed from around the seventh century, with notable works including Kadambari.

Notable writers of light poetry include Lewis Carroll, Ogden Nash, X. J. Kennedy, Willard R. Espy, Shel Silverstein, Gavin Ewart and Wendy Cope.