History of the Jews in Poland

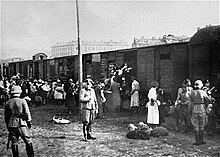

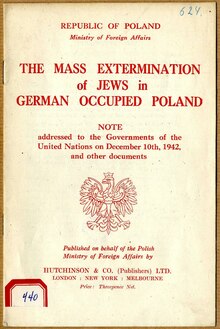

During World War II there was a nearly complete genocidal destruction of the Polish Jewish community by Nazi Germany and its collaborators of various nationalities,[5] during the German occupation of Poland between 1939 and 1945, called the Holocaust.

Polish attitudes to the Holocaust varied widely, from actively risking death in order to save Jewish lives,[20] and passive refusal to inform on them, to indifference, blackmail,[21] and in extreme cases, committing premeditated murders such as in the Jedwabne pogrom.

One of them, a diplomat and merchant from the Moorish town of Tortosa in Spanish Al-Andalus, known by his Arabic name, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, was the first chronicler to mention the Polish state ruled by Prince Mieszko I.

[35] As elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, the principal activity of Jews in medieval Poland was commerce and trade, including the export and import of goods such as cloth, linen, furs, hides, wax, metal objects, and slaves.

With the consent of the class representatives and higher officials, in 1264 he issued a General Charter of Jewish Liberties (commonly called the Statute of Kalisz), which granted all Jews the freedom to worship, trade, and travel.

[41] The Councils of Wrocław (1267), Buda (1279), and Łęczyca (1285) each segregated Jews, ordered them to wear a special emblem, banned them from holding offices where Christians would be subordinated to them, and forbade them from building more than one prayer house in each town.

Indeed, with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Poland became the recognized haven for exiles from Western Europe; and the resulting accession to the ranks of Polish Jewry made it the cultural and spiritual center of the Jewish people.

[54] After the childless death of Sigismund II Augustus, the last king of the Jagiellon dynasty, nobles (szlachta) gathered at Warsaw in 1573 and signed a document in which representatives of all major religions pledged mutual support and tolerance.

The following eight or nine decades of material prosperity and relative security experienced by Polish Jews – wrote Professor Gershon Hundert – witnessed the appearance of "a virtual galaxy of sparkling intellectual figures."

[citation needed] In this time of mysticism and overly formal Rabbinism came the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, or BeShT, (1698–1760), which had a profound effect on the Jews of Eastern Europe and Poland in particular.

[74] Eight years later, triggered by the Confederation of Bar against Russian influence and the pro-Russian king, the outlying provinces of Poland were overrun from all sides by different military forces and divided for the first time by the three neighboring empires, Russia, Austria, and Prussia.

[citation needed] The permanent council established at the instance of the Russian government (1773–1788) served as the highest administrative tribunal, and occupied itself with the elaboration of a plan that would make practicable the reorganization of Poland on a more rational basis.

One of the members of the commission, kanclerz Andrzej Zamoyski, along with others, demanded that the inviolability of their persons and property should be guaranteed and that religious toleration should be to a certain extent granted them; but he insisted that Jews living in the cities should be separated from the Christians, that those of them having no definite occupation should be banished from the kingdom, and that even those engaged in agriculture should not be allowed to possess land.

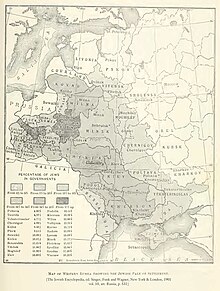

The territories which included the great bulk of the Jewish population was transferred to Russia, and thus they became subjects of that empire, although in the first half of the 19th century some semblance of a vastly smaller Polish state was preserved, especially in the form of the Congress Poland (1815–1831).

By the late 19th century, Haskalah and the debates it caused created a growing number of political movements within the Jewish community itself, covering a wide range of views and vying for votes in local and regional elections.

Other Jewish authors of the period, such as Bruno Schulz, Julian Tuwim, Marian Hemar, Emanuel Schlechter and Bolesław Leśmian, as well as Konrad Tom and Jerzy Jurandot, were less well known internationally, but made important contributions to Polish literature.

Other Polish Jews who gained international recognition are Moses Schorr, Ludwik Zamenhof (the creator of Esperanto), Georges Charpak, Samuel Eilenberg, Emanuel Ringelblum, and Artur Rubinstein, just to name a few from the long list.

[130] With the influence of the Endecja (National Democracy) party growing, antisemitism gathered new momentum in Poland and was most felt in smaller towns and in spheres in which Jews came into direct contact with Poles, such as in Polish schools or on the sports field.

[146][147] The 32% of Jewish inhabitants of Radom enjoyed considerable prominence also,[148] with 90% of small businesses in the city owned and operated by the Jews including tinsmiths, locksmiths, jewellers, tailors, hat makers, hairdressers, carpenters, house painters and wallpaper installers, shoemakers, as well as most of the artisan bakers and clock repairers.

[193][194] Following Jan Karski's report written in 1940, historian Norman Davies claimed that among the informers and collaborators, the percentage of Jews was striking; likewise, General Władysław Sikorski estimated that 30% of them identified with the communists whilst engaging in provocations; they prepared lists of Polish "class enemies".

As a result of these factors they found it easy after 1939 to participate in the Soviet occupation administration in Eastern Poland, and briefly occupied prominent positions in industry, schools, local government, police and other Soviet-installed institutions.

Some of these German-inspired massacres were carried out with help from, or active participation of Poles themselves: for example, the Jedwabne pogrom, in which between 300 (Institute of National Remembrance's Final Findings[220]) and 1,600 Jews (Jan T. Gross) were tortured and beaten to death by members of the local population.

[226] In spite of the introduction of death penalty extending to the entire families of rescuers, the number of Polish Righteous among the Nations testifies to the fact that Poles were willing to take risks in order to save Jews.

When we invaded the Ghetto for the first time – wrote SS commander Jürgen Stroop – the Jews and the Polish bandits succeeded in repelling the participating units, including tanks and armored cars, by a well-prepared concentration of fire.

With the decision of Nazi Germany to begin the Final Solution, the destruction of the Jews of Europe, Aktion Reinhard began in 1942, with the opening of the extermination camps of Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka, followed by Auschwitz-Birkenau where people were killed in gas chambers and mass executions (death wall).

At its postwar peak, up to 240,000 returning Jews might have resided in Poland mostly in Warsaw, Łódź, Kraków, Wrocław and Lower Silesia, e.g., Dzierżoniów (where there was a significant Jewish community initially consisting of local concentration camp survivors), Legnica, and Bielawa.

After 1967's Six-Day War, in which the Soviet Union supported the Arab side, the Polish communist party adopted an anti-Jewish course of action which in the years 1968–1969 provoked the last mass migration of Jews from Poland.

Hand-picked by Joseph Stalin, prominent Jews held posts in the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party including Jakub Berman, head of state security apparatus Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (UB),[301] and Hilary Minc responsible for establishing a Communist-style economy.

Helena Wolińska-Brus, a former Stalinist prosecutor who emigrated to England in the late 1960s, fought being extradited to Poland on charges related to the execution of a Second World War resistance hero Emil Fieldorf.

[314] On 17 June 2009 the future Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw launched a bilingual Polish-English website called "The Virtual Shtetl",[315] providing information about Jewish life in Poland.

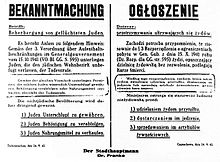

Concerning:

the Sheltering of Escaping Jews .

....There is a need for a reminder, that in accordance with paragraph 3 of the decree of 15 October 1941, on the Limitation of Residence in General Government (page 595 of the GG Register) Jews leaving the Jewish Quarter without permission will incur the death penalty .

....According to this decree, those knowingly helping these Jews by providing shelter, supplying food, or selling them foodstuffs are also subject to the death penalty

....This is a categorical warning to the non-Jewish population against:

......... 1) Providing shelter to Jews,

......... 2) Supplying them with Food,

......... 3) Selling them Foodstuffs.

Dr. Franke – Town Commander – Częstochowa 9/24/42