Political history of the Philippines

Early polities in what is now the Philippines were small entities known as barangays, although some larger states were established following the arrival of Hinduism and Islam through regional trade networks.

Despite strengthening Communist and Islamic separatist rebellions, Marcos retained firm control of the country until economic issues and disenchantment with corruption led to greater opposition.

Since then, an unstable multi-party system has emerged on the national level, which has been challenged by a series of crises including several attempted coups, a presidential impeachment, and two more public mass movements.

Before the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, the Philippines was split into numerous barangays, small states that were linked through region-wide trade networks.

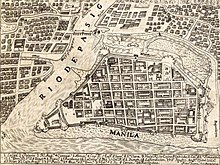

Spain gradually conquered the majority of the modern Philippines, although full control was never established over some Muslim areas in the south and in the Cordillera highlands.

[13] In a process beginning in the late 18th century that would continue for the remainder of Spanish rule, the government tried to shift power from the friars of independent religious orders towards the "secular clergy" of Catholic priests.

[11]: 41 Spanish served as a common language for the growing local elite, who shared a Western educational background despite varied ethnolinguistic origins.

[6]: 137, 145 This revolution gained the support of the municipal elite outside of the major cities, who found themselves with significantly greater control as Spanish administrative and religious authorities were forced out by the revolutionaries.

[7]: 1076 While they rejected proposals for a federal system or autonomy in favor of a more easily controlled centralized system,[27]: 179 [28]: 48 the Americans gave Filipinos limited self-government at the local level by 1901,[32]: 150–151 holding the first municipal elections,[33] and passed the Philippine Organic Act in 1902 to introduce a national government[34]: 110–111 and regularize civilian rule, designating the Philippine Commission as a legislative body, with membership consisting of Americans appointed by the U.S.

[36]: 11–12 U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt ended U.S. hostilities and proclaimed a full and complete pardon and amnesty to revolutionaries on July 4, 1902, and abolished the office of U.S. Military Governor in the Philippines.

[1]: 126–127 These individuals were considered traitors by the ongoing Philippine revolution, but their alliance with the American military led members of the party to be placed in positions of power at all levels and branches of government.

[36]: 15 In rural areas, a sudden vacuum of elite power led to the formation of new local governments by the remaining populace, beginning the Hukbalahap Rebellion.

[10]: 145 A left-wing political movement that spawned from the Hukbalahap fight against the Japanese was suppressed by the former elite with American support, leading to the continuation of the rebellion against the new government.

[56]: 41 The impact of the war led to a weaker civil service and a reduction in the dominance of Manila, with provincial politicians gaining political power and in some cases de facto autonomy.

Despite the landed elite continuing to dominate the legislature,[46]: 14–15 a diversifying post-war economy saw politicians who were not primarily from agricultural backgrounds come to executive power.

[35]: 80 Marcos' infrastructure projects were the feature policy of his term,[70] he was the first president to be re-elected, in 1969, although the election was tainted by violence and allegations of fraud and vote buying.

[62]: 64 Communist rebellion strengthened during Marcos' rule,[1]: 219–220 and a Moro insurgency emerged in Mindanao as tensions surrounding Christian immigration combined with a more empowered national government.

[46]: 46–47 Military training also shifted, with an increasing emphasis on humanities, in order to allow officers to more effectively handle civilian administrative roles.

[67]: 70 The changes implemented by Marcos sought to eliminate regional power centers and instead strengthen links between his national government and the general public.

[61]: 437 Marcos ended martial law in 1981, shortly before a visit to the country by Pope John Paul II, although he retained immense executive powers.

As elements of the military became more involved in governing, including abetting Marcos in increasing his control, morale decreased among those continuing to fight the rebellion.

[26]: 125 [22]: 6 This "freedom constitution" declared the Aquino Government to have been installed through a direct exercise of the power of the Filipino people assisted by units of the New Armed Forces of the Philippines.

[62]: 67 The practice of recruiting retired military officers for some executive branch roles, such as ambassadorships, or within cabinet, that was started by Marcos and continued after the restoration of democracy.

[85]: 28 [87]: 282 [88]: 91 Aquino's government was mired by coup attempts,[59] high inflation and unemployment,[89] and natural calamities,[89][90] but introduced limited land reform[1]: 235 [91][92][93] and market liberalization.

[117] The administration launched an "all-out war" against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front that saw the government retaking Camp Abubakar, the main rebel encampment.

[115]: 257–258 [118] Despite the popular anti-rebel stance, the administration was embroiled in charges of cronyism and corruption; a scandal involving jueteng gambling led to his impeachment by the House of Representatives.

[138]: 42–43 However, natural calamities,[139] along with scams on the use of pork barrel and other discretionary funds coming to light, led to rising opposition in the final years of the administration.

[138]: 45 In 2016, Aquino's handpicked successor, Mar Roxas, was decisively defeated by Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte in the 2016 Presidential Election.

[137]: 18 His election victory was propelled by growing public frustration over the tumultuous post-EDSA democratic governance, which favored political and economic elite over ordinary Filipinos.

[154][155] The administration made peace with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, agreeing to expand and empower autonomy in Muslim areas, replacing the ARMM with the more powerful Bangsamoro region.