Marco Polo

Marco was appointed to serve as Kublai's foreign emissary, and he was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout the empire and Southeast Asia, visiting present-day Burma, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

His account provided the Europeans with a clear picture of the East's geography and ethnic customs, and it included the first Western record of porcelain, gunpowder, paper money, and some Asian plants and exotic animals.

[18] In contrast to the general consensus, there are theories suggesting that Marco Polo's birthplace was the island of Korčula[19][20][10][12][21][22] or Constantinople[10][23] but such hypotheses failed to gain acceptance among most scholars and have been countered by other studies.

According to the 15th-century humanist Giovanni Battista Ramusio, his fellow citizens awarded him this nickname when he came back to Venice because he kept on saying that Kublai Khan's wealth was counted in millions.

He was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout his empire and in Southeast Asia, (such as in present-day Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Vietnam),[5][6] but also entertained the Khan with stories and observations about the lands he saw.

[citation needed] However, around 1291, he finally granted permission, entrusting the Polos with his last duty: accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin, who was to become the consort of Arghun Khan, in Persia.

He spent several months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to a fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa,[31] who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes and current affairs from China.

[50] Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299,[31] and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle in the meantime had purchased a large palazzo in the zone named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo (Corte del Milion).

Marco told him that during his return trip to the South China Sea, he had spotted what he describes in a drawing as a star "shaped like a sack" (in Latin: ut sacco) with a big tail (magna habens caudam); most likely a comet.

[38] Polo is clearly mentioned again after 1305 in Maffeo's testament from 1309 to 1310, in a 1319 document according to which he became owner of some estates of his deceased father, and in 1321, when he bought part of the family property of his wife Donata.

[63] An authoritative version of Marco Polo's book does not and cannot exist, for the early manuscripts differ significantly, and the reconstruction of the original text is a matter of textual criticism.

[70] One of the early manuscripts Iter Marci Pauli Veneti was a translation into Latin made by the Dominican brother Francesco Pipino [it] in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice.

[72] The published editions of Polo's book rely on single manuscripts, blend multiple versions together, or add notes to clarify, for example in the English translation by Henry Yule.

[74] Sharon Kinoshita's 2016 version takes as its source the Franco-Italian 'F' manuscript,[75] and invites readers to "focus on the text as the product of a larger European (and Eurasian) literary and commercial culture", rather than questions of veracity of the account.

[80] After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy).

They followed the suggestion of Theobald Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt, and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at the age of fifteen or sixteen.

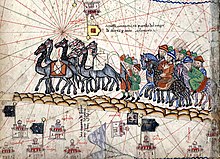

The Polos wanted to sail straight into China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland through the Silk Road, until reaching Kublai's summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou.

The Dominican father Francesco Pipino was the author of a translation into Latin, Iter Marci Pauli Veneti in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice.

[99] Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as 'barbarians' who appeared to belong to 'some other world'.

It is also largely free of the gross errors found in other accounts such as those given by the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta who had confused the Yellow River with the Grand Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain was made from coal.

While Polo describes paper money and the burning of coal, he fails to mention the Great Wall of China, tea, Chinese characters, chopsticks, or footbinding.

[109] Wood maintains that it is more probable that Polo went only to Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) and some of the Italian merchant colonies around the Black Sea, picking hearsay from those travellers who had been farther east.

[41] The book has been criticised by figures including Igor de Rachewiltz (translator and annotator of The Secret History of the Mongols) and Morris Rossabi (author of Kublai Khan: his life and times).

[120] Igor de Rachewiltz's review, which refutes Wood's points, concludes with a strongly-worded condemnation: "I regret to say that F. W.'s book falls short of the standard of scholarship that one would expect in a work of this kind.

[108] In the 2010s the Chinese scholar Peng Hai claimed to have identified Marco Polo with a certain "Boluo" (孛罗; 孛羅; Bóluō), a courtier of the emperor, who is mentioned in Volume 119 of the History of Yuan (Yuánshǐ) commissioned by the succeeding Ming dynasty.

These conjectures seem to be supported by the fact that in addition to the imperial dignitary Saman (the one who had arrested the official named "Boluo"), the documents mention his brother, Xiangwei (相威; Xiāngwēi).

[129][126] Stephen G. Haw challenges this idea that Polo exaggerated his own importance, writing that, "contrary to what has often been said ... Marco does not claim any very exalted position for himself in the Yuan empire.

[131] Another contradictory claim is at chapter 145 when the Book of Marvels states that the three Polos provided the Mongols with technical advice on building mangonels during the Siege of Xiangyang, Adonc distrent les .II.

Elvin concludes that "those who doubted, although mistaken, were not always being casual or foolish", but "the case as a whole had now been closed": the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not always final, witness.

Benjamin B. Olshin a historian who wrote for the University of Chicago Press has been unable to "establish the authenticity" of these maps once owned by Marcian Rossi, an Italian immigrant living in California during the 1930s known for peddaling hoaxes.