Pope Manufacturing Company

[2] Though Pope Manufacturing had filed for incorporation in Connecticut, it continued to base its offices and many of its operations in Boston.

[3] Albert and Edward Pope operated a factory at 87 Summer Street in Boston as early as 1874 for the production of hand-held cigarette rolling machines.

Pope had ridden an imported Excelsior Duplex model penny farthing to the meeting, which Fairfield inspected.

[8] George Bidwell, an independent salesman from Buffalo, New York, purchased an imported Excelsior Duplex high-wheeler from Pope.

Learning in a correspondence from Pope that he would be producing his own bicycle, Bidwell started taking orders for the Columbias.

The Special Columbia offered "a closed Stanley-style head," a "built-in" ball-bearing assembly, and full nickel-plating for $132.50.

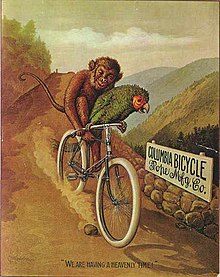

[12] He used the latest technologies in his bicycles—inventions such as ball bearings in all moving parts, and hollow steel tubes for the frame, and he spent a great deal of money promoting bicycle clubs, journals, and races.

[12] Ordinaries (high-wheelers or penny farthings) were driven by cranks and pedals attached directly to an oversized front wheel.

Many mishaps included the projection of the rider head-first over the handle bars: an event occurring with enough frequency to earn the name, header.

In 1886, after seeing some Rovers and touring a Rover-factory, Alfred Pope claimed that the safety bicycle was nothing more than a fad, and made no plans at that time to produce his own version.

[13] He urged Pope to design its own safety bicycle while predicting "the old high wheel was doomed.

At a time when Pope charged $125 for a Columbia, Overman Wheel Company was marketing a bicycle for wage workers, who might earn $1 per day.

Instead of reducing cost and price on the Columbias, Pope decided to produce a separate line to compete with Overman.

[16] Around 1890, Pope started another manufacturer, Hartford Cycle Company in order to create a new line with a mid-price niche.

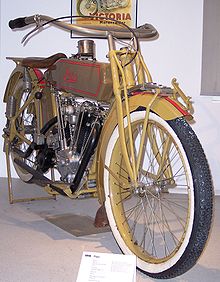

[17] Ordinaries had used a heavy pipe, but the safeties used twenty-seven feet of tubing: solid round bar would weigh down the machine.

[18] Two Pope employees, Henry Souther and Harold Hayden Eames, collaborated on a new process for producing bicycle tubing.

Souther had been experimenting with stress tolerances of different metals, and concluded that steel with five-percent nickel alloy would be ideal for bicycle tubing.

Eames devised a process for converting metal sheets into billets, which could be cold-drawn through dies with methods and equipment already in use at the Pope tube works.

Founded by John Gray in 1885, Hartford Rubber Works imported raw material from Sumatra and produced solid tires.

The tubular frames, seats, fenders, wheels, hubs, brakes, front fork assembly, headlight, and wiring harnesses were made in the United States.

This company produced the tubular frames, long seats, fenders, wheels, hubs, brakes, front fork assembly, headlight, and wiring harnesses in the United States.

[23] Pope tried to re-enter the automobile manufacturing market in 1901 by acquiring a number of small firms, but the process was expensive and competition in the industry was heating up.