Population bottleneck

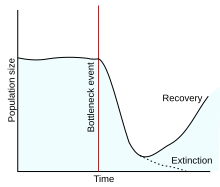

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as genocide, speciocide, widespread violence or intentional culling.

A slightly different form of bottleneck can occur if a small group becomes reproductively (e.g., geographically) separated from the main population, such as through a founder event, e.g., if a few members of a species successfully colonize a new isolated island, or from small captive breeding programs such as animals at a zoo.

Alternatively, invasive species can undergo population bottlenecks through founder events when introduced into their invaded range.

[7] According to a 1999 model, a severe population bottleneck, or more specifically a full-fledged speciation, occurred among a group of Australopithecina as they transitioned into the species known as Homo erectus two million years ago.

The controversial Toba catastrophe theory, presented in the late 1990s to early 2000s, suggested that a bottleneck of the human population occurred approximately 75,000 years ago, proposing that the human population was reduced to perhaps 10,000–30,000 individuals[14] when the Toba supervolcano in Indonesia erupted and triggered a major environmental change.

[17] In 2000, a Molecular Biology and Evolution paper suggested a transplanting model or a 'long bottleneck' to account for the limited genetic variation, rather than a catastrophic environmental change.

The animals living today are all descended from 12 individuals and they have extremely low genetic variation, which may be beginning to affect the reproductive ability of bulls.

An extreme example of a population bottleneck is the New Zealand black robin, of which every specimen today is a descendant of a single female, called Old Blue.

[22] These declines in population were the result of hunting and habitat destruction, but the random consequences have also caused a great loss in species diversity.

DNA analysis comparing the birds from 1990 and mid-century shows a steep genetic decline in recent decades.

[24][25] Bottlenecks also exist among pure-bred animals (e.g., dogs and cats: pugs, Persian) because breeders limit their gene pools to a few (show-winning) individuals for their looks and behaviors.

[28] This reduced genetic diversity in many crops could lead to broader susceptibility to new diseases or pests, which threatens global food security.

[29] Research showed that there is incredibly low, nearly undetectable amounts of genetic diversity in the genome of the Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis).

A population bottleneck was created in the 1970s through the conservation efforts of the endangered Mauna Kea silversword (Argyroxiphium sandwicense ssp.