Ungulate protoparvovirus 1

The disease develops mainly when seronegative dams are exposed oronasally to the virus anytime during about the first half of gestation, and conceptuses are subsequently infected transplacentally before they become immunocompetent.

[4][5][6][7][8] In addition to its direct causal role in reproductive failure, PPV can potentiate the effects of porcine circovirus type II (PCV2) infection in the clinical course of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS).

[9][10] Acute infection of postnatal pigs, including pregnant dams that subsequently develop reproductive failure, is usually subclinical.

[11][12][13][14][15][16] However, in young pigs and probably in older breeding stock as well, the virus replicates extensively and is found in many tissues and organs with a high mitotic index.

Many pigs, irrespective of age or sex, have a transient, usually mild, leukopenia sometime within 10 days after initial exposure to the virus.

[18][19] However, there is no experimental evidence to suggest that PPV either replicates extensively in the intestinal crypt epithelium or causes enteric disease as do parvoviruses of several other species.

A mature virion has cubic symmetry, two or three capsid proteins, a diameter of approximately 20 nm, 32 capsomeres, no envelope or essential lipids, and a weight of 5.3 × 106 daltons.

Viral infectivity, hemagglutinating activity, and antigenicity are remarkably resistant to heat, a wide range of hydrogen ion concentrations, and enzymes.

[46][47][48] If either fetal or adult bovine serum is incorporated in the nutrient medium of cell cultures used to propagate PPV, it should be pretested for viral inhibitors.

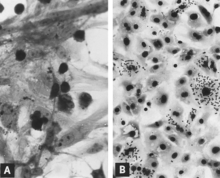

Infected cells commonly seen in the lung of fetuses that develop a high titer of antibody for PPV probably represent this stage of replication (see Fig.

In major swine-producing areas such as the midwestern United States, infection is enzootic in most herds, and with few exceptions sows are immune.

In addition, a large proportion of gilts are naturally infected with PPV before they conceive, and as a result they develop an active immunity that probably persists throughout life.

The virus is thermostable, is resistant to many common disinfectants,[78] and may remain infectious for months in secretions and excretions from acutely infected pigs.

It was shown experimentally that although pigs transmitted PPV for only about 2 weeks after exposure, the pens in which they were initially kept remained infectious for at least 4 months.

After day 8, isolation was accomplished by cocultivating lymph node fragments with fetal porcine kidney cells (Mengeling, unpublished data 1976).

Transplacental infection also follows maternal exposure after midgestation, but fetuses usually survive without obvious clinical effects in utero.

The virus adheres tenaciously to the external surface of the zona pellucida of the fertilized porcine ovum,[92][93] and although it apparently cannot penetrate this layer, speculation is that it could pose a threat to the embryo after hatching.

With the possible exception of the uterine changes alluded to in the preceding paragraph, PPV-induced reproductive failure is caused by the direct effect of the virus on the conceptus.

Damage to the fetal circulatory system is indicated by edema, hemorrhage, and the accumulation of large amounts of serosanguineous fluids in body cavities.

These include a variable degree of stunting and sometimes an obvious loss of condition before other external changes are apparent; occasionally, an increased prominence of blood vessels over the surface of the fetus due to congestion and leakage of blood into contiguous tissues; congestion, edema, and hemorrhage with accumulation of serosanguineous fluids in body cavities; hemorrhagic discoloration becoming progressively darker after death; and dehydration (mummification).

Microscopic lesions consist primarily of extensive cellular necrosis in a wide variety of tissues and organs[95][98] (Fig.

Both general types of microscopic lesions (i.e., necrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration) may develop in fetuses infected near midgestation[95] when the immune response is insufficient to provide protection.

If gilts but not sows are affected, maternal illness is not seen during gestation, there are few or no abortions or fetal developmental anomalies, and other evidence suggests an infectious disease, then a tentative diagnosis of PPV-induced reproductive failure can be made.

The relative lack of maternal illness, abortions, and fetal developmental anomalies differentiates PPV from most other infectious causes of reproductive failure.

When all embryos of a litter die and are completely resorbed after the first few weeks of gestation, the dam may remain endocrinologically pregnant and not return to estrus until after the expected time of farrowing.

[5] Moreover, the procedure is time-consuming, and contamination is a constant threat because of the stability of PPV in the laboratory[31] and because cell cultures are sometimes unknowingly prepared from infected tissues.

[11][60][17][80][104] When serum is not available, body fluids collected from fetuses or their viscera that have been kept in a plastic bag overnight at 4?C have been used successfully to demonstrate antibody.

Although inactivated vaccine provides maximum safety, there is experimental evidence that PPV can be sufficiently attenuated so that it is unlikely to cause reproductive failure even if inadvertently administered during gestation.

[113] The apparent safety of MLV vaccine may be due to its reduced ability to replicate in tissues of the intact host and cause the level of viremia needed for transplacental infection.

Vaccines are used extensively in the United States and in several other countries where PPV has been recognized as an economically important cause of reproductive failure.