Portraiture of Elizabeth I

The portraiture of Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) spans the evolution of English royal portraits in the early modern period (1400/1500-1800), from the earliest representations of simple likenesses to the later complex imagery used to convey the power and aspirations of the state, as well as of the monarch at its head.

Later portraits of Elizabeth layer the iconography of empire—globes, crowns, swords and columns—and representations of virginity and purity, such as moons and pearls, with classical allusions, to present a complex "story" that conveyed to Elizabethan era viewers the majesty and significance of the 'Virgin Queen'.

Unlike her contemporaries in France, Elizabeth never granted rights to produce her portrait to a single artist, although Nicholas Hilliard was appointed her official limner, or miniaturist and goldsmith.

[2] Elizabeth sat for a number of artists over the years, including Hilliard, Cornelis Ketel, Federico Zuccaro or Zuccari, Isaac Oliver, and most likely to Gower and Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger.

Courtiers commissioned heavily symbolic paintings to demonstrate their devotion to the queen, and the fashionable long galleries of later Elizabethan country houses were filled with sets of portraits.

By his second visit, Holbein had already begun to move away from a strictly realist depiction; in his Jane Seymour, "the figure is no longer seen as displacing with its bulk a recognizable section of space: it approaches rather to a flat pattern, made alive by a bounding and vital outline".

Mor, who had risen rapidly to prominence in 1540s, worked across Europe for the Habsburgs in a tighter and more rigid version of Titian's compositional manner, drawing also on the North Italian style of Moretto.

He wrote, "The painter...is unknown, but in a competently Flemish style he depicts the daughter of Anne Boleyn as quiet and studious-looking, ornament in her attire as secondary to the plainness of line that emphasizes her youth.

Great is the contrast with the awesome fantasy of the later portraits: the pallid, mask-like features, the extravagance of headdress and ruff, the padded ornateness that seemed to exclude all humanity.

In the Art of Limming, Hilliard cautioned against all but the minimal use of chiaroscuro modelling seen in his works, reflecting the views of his patron: "seeing that best to show oneself needeth no shadow of place but rather the open light...Her Majesty..chose her place to sit for that purpose in the open alley of a goodly garden, where no tree was near, nor any shadow at all..."[16] From the 1570s, the government sought to manipulate the image of the queen as an object of devotion and veneration.

In this image, Catholic Mary and her husband Philip II of Spain are accompanied by Mars, the god of War, on the left, while Protestant Elizabeth on the right ushers in the goddesses Peace and Plenty.

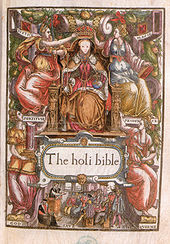

Hilliard's appointment as miniaturist to the Crown included the old sense of a painter of illuminated manuscripts and he was commissioned to decorate important documents, such as the founding charter of Emmanuel College, Cambridge (1584), which has an enthroned Elizabeth under a canopy of estate within an elaborate framework of Flemish-style Renaissance strapwork and grotesque ornament.

[35] Recent conservation work has revealed that Elizabeth's now-iconic pale complexion in this portrait is the result of deterioration of red lake pigments, which has also altered the coloring of her dress.

It is against this backdrop that the first of a long series of portraits appears, depicting Elizabeth with heavy symbolic overlays of the possession of an empire based on mastery of the seas.

[citation needed] Strong points out that there is no trace of this iconography in portraits of Elizabeth prior to 1579, and identifies its source as the conscious image-making of John Dee, whose 1577 General and Rare Memorials Pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation encouraged the establishment of English colonies in the New World supported by a strong navy, asserting Elizabeth's claims to an empire via her supposed descent from Brutus of Troy and King Arthur.

This painting's patron was likely Sir Christopher Hatton, as his heraldic badge of the white hind appears on the sleeve of one of the courtiers in the background, and the work may have expressed opposition to the proposed marriage of Elizabeth to François, Duke of Anjou.

[55][56] The Queen is flanked by two columns behind, probably a reference to the famous impresa of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, Philip II of Spain's father, which represented the pillars of Hercules, gateway to the Atlantic Ocean and the New World.

[57] In the background view on the left, English fireships threaten the Spanish fleet, and on the right the ships are driven onto a rocky coast amid stormy seas by the "Protestant Wind".

[58] The various threads of mythology and symbolism that created the iconography of Elizabeth I combined into a tapestry of immense complexity in the years following the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

Sir Walter Raleigh had begun to use Diana, and later Cynthia, as aliases for the queen in his poetry around 1580, and images of Elizabeth with jewels in the shape of crescent moons or the huntress's arrows begin to appear in portraiture around 1586 and multiply through the remainder of the reign.

Many versions of this painting were made, likely in Gheeraerts' workshop, with the allegorical items removed and Elizabeth's features "softened" from the stark realism of her face in the original.

Only a single finished miniature from this pattern survives, with the queen's features softened, and Strong concludes that this realistic image from life of the aging Elizabeth was not deemed a success.

In 1596, the Privy Council ordered that unseemly portraits of the queen which had caused her "great offence" should be sought out and burnt, and Strong suggest that these prints, of which comparatively few survive, may be the offending images.

Strong writes "It must have been exposure to the searching realism of both Gheeraerts and Oliver that provoked the decision to suppress all likenesses of the queen that depicted her as being in any way old and hence subject to mortality.

Faithful resemblance to the original is only to be found in the accounts of contemporaries, as in the report written in 1597 by André Hurault de Maisse, Ambassador Extraordinary from Henry IV of France, after an audience with the 64-year-old queen, during which he noted, "her teeth are very yellow and unequal ... and on the left side less than on the right.

"[64] All subsequent images rely on a face pattern devised by Nicholas Hilliard sometime in the 1590s called by art historians the "Mask of Youth", portraying Elizabeth as ever-young.

[63][65] Some 16 miniatures by Hilliard and his studio are known based on this face pattern, with different combinations of costume and jewels likely painted from life, and it was also adopted by (or enforced on) other artists associated with the Court.

In this painting, an ageless Elizabeth appears dressed as if for a masque, in a linen bodice embroidered with spring flowers and a mantle draped over one shoulder, her hair loose beneath a fantastical headdress.

[74] The many portraits of Elizabeth I constitute a tradition of image highly steeped in classical mythology and the Renaissance understanding of English history and destiny, filtered by allusions to Petrarch's sonnets and, late in her reign, to Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene.

There are no better examples of this than the quite extraordinary portraits of the queen herself, which increasingly, as the reign progressed, took on the form of collections of abstract pattern and symbols disposed in an unnaturalistic manner for the viewer to unravel, and by doing so enter into an inner vision of the idea of monarchy.