Stuart period

The vast land holdings seized from the monasteries under Henry VIII of England in the 1530s were sold mostly to local gentry, greatly expanding the wealth of that class of gentlemen.

On his return, Cromwell tried to galvanise the Rump into setting dates for new elections, uniting the three kingdoms under one polity, and to put in place a broad-brush, tolerant national church.

However, the Rump vacillated in setting election dates, and although it put in place a basic liberty of conscience, it failed to produce an alternative for tithes or dismantle other aspects of the existing religious settlement.

Although Cromwell did not subscribe to Harrison's apocalyptic, Fifth Monarchist beliefs – which saw a sanhedrin as the precondition of Christ's rule on earth – he was attracted by the idea of an assembly made up of a cross-section of sects.

Their position was further harmed by a tax proposal by Major General John Desborough to provide financial backing for their work, which Parliament voted down for fear of a permanent military state.

The Whig model, dominant in the 19th century, saw an inherent conflict between irresistible, truly English ideals of liberty and individualism represented by The Puritans and Roundheads, overcoming the medieval concept of the king as the unquestionable voice of God.

Meanwhile, in the late 19th century, the remarkably high quality scholarship of archivally oriented historians, especially Samuel Rawson Gardiner and Charles Harding Firth had provided the rich details on national politics, practically on a day-by-day basis.

It fought back against its exclusion from the power, patronage and payoff by an extravagant court, by the king's swelling state bureaucracy and by the nouveau riche financiers in London.

"Revisionists" came to the fore, rejecting both Whig and Marxist approaches because they assumed historical events were the automatic playing out of mysterious forces such as "liberty"and "class conflict.

The current scholarly solution is to emphasise what historians call the "British problem", involving the impossible tensions occurring when a single person tried to hold together his three kingdoms with their entirely different geographical, ethnic, political, and religious values and traditions.

Parliament watched Charles' ministers closely for any signs of defiance, and was ready to use the impeachment procedure to remove offenders and even to pass bills of attainder to execute them without a trial.

Harris says, "At the center of this world was a libertine court – a society of Restoration rakes given more to drinking, gambling, swearing and whoring than to godliness – presided over by the King himself and his equally rakish brother James, Duke of York.

[50] Cromwell changed all that with his New Model Army of 50,000 men, that proved vastly more effective than untrained militia, and enabled him to exert a powerful control at the local level over all of England.

What they got instead was the vision of William of Orange, shared by most leading Englishmen, that emphasised consent of all the elites, religious toleration of all Protestant sects, free debate in Parliament and aggressive promotion of commerce.

[59][60] The primary reason the English elite called on William to invade England in 1688 was to overthrow the king James II, and stop his efforts to reestablish Catholicism and tolerate Puritanism.

Private investors created the Bank of England in 1694; it provided a sound system that made financing wars much easier by encouraging bankers to loan money.

Louis XIV tried to undermine this strategy by refusing to recognise William as king of England, and by giving diplomatic, military and financial support to a series of pretenders to the English throne, all based in France.

[71][72] For practically her entire reign, the central issue was the War of the Spanish Succession in which Britain played a major role in the European-wide alliance against Louis XIV of France.

The Duchess took revenge in an unflattering description of the Queen in her memoirs as ignorant and easily led, which was a theme widely accepted by historians until Anne was re-assessed in the late 20th-century.

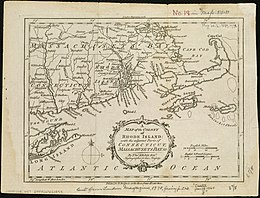

The new Britain used its power to undermine the clanship system in the Scottish Highlands[80] Ambitious Scots now had major career opportunities in the fast-growing overseas British colonies, and in the rapidly growing industrial and financial communities of England.

[85] Historians have recently placed stress on how people at the time dealt with the supernatural, not just in formal religious practice and theology, but in everyday life through magic and witchcraft.

Judges across England sharply increased their investigation of accused 'witches', thus generating a body of highly detailed local documentation that has provided the main basis for recent historical research on the topic.

[90] Historian Peter Homer has emphasised the political basis of the witchcraft issue in the 17th century, with the Puritans taking the lead in rooting out the Devil's work in their attempt to depaganise England and build a godly community.

Historian Mark Pendergast observes: Lloyd's Coffee House opened in 1686 and specialised in providing shipping news for a clientele of merchants, insurers, and shipowners.

Numerous architects worked on the decorative arts, designing intricate wainscoted rooms, dramatic staircases, lush carpets, furniture, and clocks in country houses open to tourism.

In the Tudor and Stuart periods the main foreign policy goal (besides protecting the homeland from invasion) was the building a worldwide trading network for its merchants, manufacturers, shippers and financiers.

")[126] At the time, Europe was deeply polarised, and on the verge of the massive Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), with the smaller established Protestant states facing the aggression of the larger Catholic empires.

The marriage of James' daughter Princess Elizabeth to Frederick V, Elector Palatine on 14 February 1613 was more than the social event of the era; the couple's union had important political and military implications.

[129] Frederick's election as King of Bohemia in 1619 deepened the Thirty Years' War—a conflagration that destroyed millions of lives in central Europe, but only barely touched Britain.

In the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–74), the British counted on a new alliance with France but the outnumbered Dutch outsailed both of them, and King Charles II ran short of money and political support.