Richard II of England

[3] This anecdote, and the fact that his birth fell on the feast of Epiphany, was later used in the religious imagery of the Wilton Diptych, where Richard is one of three kings paying homage to the Virgin and Child.

[3] The rebellion started in Kent and Essex in late May, and on 12 June, bands of peasants gathered at Blackheath near London under the leaders Wat Tyler, John Ball, and Jack Straw.

[3] The King set out by the River Thames on 13 June, but the large number of people thronging the banks at Greenwich made it impossible for him to land, forcing him to return to the Tower.

The King's men grew restive, an altercation broke out, and William Walworth, the Lord Mayor of London, pulled Tyler down from his horse and killed him.

It is likely, though, that the events impressed upon him the dangers of disobedience and threats to royal authority, and helped shape the absolutist attitudes to kingship that would later prove fatal to his reign.

[22] It had diplomatic significance; in the division of Europe caused by the Western Schism, Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire were seen as potential allies against France in the ongoing Hundred Years' War.

[24] Michael de la Pole had been instrumental in the marriage negotiations;[3] he had the King's confidence and gradually became more involved at court and in government as Richard came of age.

[3] With Gaunt gone, the unofficial leadership of the growing dissent against the King and his courtiers passed to Buckingham – who had by now been created Duke of Gloucester – and Richard Fitzalan, 4th Earl of Arundel.

[3] At the parliament of October that year, Michael de la Pole – in his capacity of chancellor – requested taxation of an unprecedented level for the defence of the realm.

The aggressive foreign policy of the Lords Appellant failed when their efforts to build a wide, anti-French coalition came to nothing, and the north of England fell victim to a Scottish incursion.

He outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly.

[3] These actions were made possible primarily through the collusion of John of Gaunt, but with the support of a large group of other magnates, many of whom were rewarded with new titles, and were disparagingly referred to as Richard's "duketti".

[68] A threat to Richard's authority still existed, however, in the form of the House of Lancaster, represented by John of Gaunt and his son Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Hereford.

[66] A parliamentary committee decided that the two should settle the matter by battle, but at the last moment Richard exiled the two dukes instead: Mowbray for life, Bolingbroke for ten years.

It delegated all parliamentary power to a committee of twelve lords and six commoners chosen from the King's friends, making Richard an absolute ruler unbound by the necessity of gathering a Parliament again.

[74] In the last years of Richard's reign, and particularly in the months after the suppression of the appellants in 1397, the King enjoyed a virtual monopoly on power in the country, a relatively uncommon situation in medieval England.

[77] Richard's approach to kingship was rooted in his strong belief in the royal prerogative, the inspiration of which can be found in his early youth, when his authority was challenged first by the Peasants' Revolts and then by the Lords Appellant.

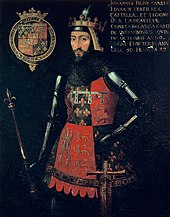

Unlike any other English king before him, he had himself portrayed in panel paintings of elevated majesty,[83] of which two survive: an over life-size Westminster Abbey portrait (c. 1390), and the Wilton Diptych (1394–1399), a portable work probably intended to accompany Richard on his Irish campaign.

[85] Richard's expenditure on jewellery, rich textiles and metalwork was far higher than on paintings, but as with his illuminated manuscripts, there are hardly any surviving works that can be connected with him, except for a crown, "one of the finest achievements of the Gothic goldsmith", that probably belonged to his wife Anne.

Fifteen life-size statues of kings were placed in niches on the walls, and the hammer-beam roof by the royal carpenter Hugh Herland, "the greatest creation of medieval timber architecture", allowed the original three Romanesque aisles to be replaced with a single huge open space, with a dais at the end for Richard to sit in solitary state.

[94] Richard was interested in occult topics such as geomancy, which he viewed as a greater discipline that included philosophy, science, and alchemic elements and commissioned a book on,[95] and sponsored writing and discussion of them in his court.

[105] However, Bolingbroke was not next in line to the throne; the heir presumptive was Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, great-grandson of Edward III's second surviving son, Lionel, Duke of Clarence.

[j] According to the official record, read by the Archbishop of Canterbury during an assembly of lords and commons at Westminster Hall on Tuesday 30 September, Richard gave up his crown willingly and ratified his deposition citing as a reason his own unworthiness as a monarch.

The King succumbed to blind rage, ordered his own release from the Tower, called his cousin a traitor, demanded to see his wife, and swore revenge, throwing down his bonnet, while Henry refused to do anything without parliamentary approval.

[108] When parliament met to discuss Richard's fate, John Trevor, Bishop of St Asaph, read thirty-three articles of deposition that were unanimously accepted by lords and commons.

Henry IV's government dismissed him as an impostor, and several sources from both sides of the border suggest the man had a mental illness, one also describing him as a "beggar" by the time of his death in 1419, but he was buried as a king in Blackfriars, Stirling, the local Dominican friary.

Meanwhile, Henry V – in an effort both to atone for his father's act of murder and to silence the rumours of Richard's survival – had decided to have the body at King's Langley reinterred in Westminster Abbey on 4 December 1413.

[114] While the Westminster Abbey portrait probably shows a good similarity of the King, the Wilton Diptych portrays him as significantly younger than he was at the time; it must be assumed that he had a beard by this point.

However, this promise was never fulfilled, as the cost of the royal retinue, the opulence of court and Richard's lavish patronage of his favourites proved as expensive as war had been, without offering commensurate benefits.

[80] As for his policy of military retaining, this was later emulated by Edward IV and Henry VII, but Richard II's exclusive reliance on the county of Cheshire hurt his support from the rest of the country.