Nadir of American race relations

[3][4][5] Loewen chooses later dates, arguing that the post-Reconstruction era was in fact one of widespread hope for racial equity due to idealistic Northern support for civil rights.

In Loewen's view, the true nadir only began when Northern Republicans ceased supporting Southern Blacks' rights around 1890, and it lasted until the United States entered World War II in 1941.

[7] In the early part of the 20th century, some white historians put forth the claim that Reconstruction was a tragic period, when Republicans who were motivated by revenge and profit used troops to force Southerners to accept corrupt governments that were run by unscrupulous Northerners and unqualified Blacks.

Another Columbia professor, John Burgess, was notorious for writing that "black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself... created any civilization of any kind.

[10] The text discusses the revisionist perspective on the history of Reconstruction in the United States, which contrasts with the traditional view that depicted it negatively as an imposition by Northern Radicals.

While Du Bois aimed to present a straightforward narrative highlighting the experiences of Black individuals, his work is criticized for lacking rigorous historical methodology and relying on limited sources, raising questions about its scholarly validity.

The text emphasizes the importance of critically evaluating historical accounts, noting that some interpretations, like Du Bois’s dismissal of certain evidence, may oversimplify complex realities, such as the violent repercussions faced by Southern whites during this period.

Throughout most of the 20th century, Reconstruction was viewed as a dismal and disgraceful aftermath of the Civil War, characterized by Northern Radicals and carpetbaggers imposing their harshest fantasies on a defeated South.

Despite its ambition, the work is critiqued for its reliance on limited sources and lack of original archival research, raising concerns regarding its scholarly validity.

The text emphasizes the significance of the Reconstruction period, which established a long-lasting system of racial hierarchy and injustice in America, yet remains poorly understood by many.

The Equal Justice Initiative’s 2015 report reveals over 4,400 documented lynchings of Black individuals from 1877 to 1950, with at least 2,000 victims during Reconstruction alone, underscoring the era’s brutal racial violence.

[14] For several years after the Civil War, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed that it was willing to intervene to protect the rights of Black Americans.

More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Civil War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of money and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency.

"[18] In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872, thousands of White League militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won.

They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops.

President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a general had led the Union to victory in the Civil War, initially refused to send troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to.

This change in perspective led to Supreme Court rulings that curtailed Reconstruction laws, resulting in only a few Southern states remaining under Republican control by 1876.

The contentious presidential election that year culminated in a compromise granting Democrats control of the South in exchange for recognizing Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as president, marking the end of federal protection for former slaves’ rights.

Democrats used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such as poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes.

[26] South Carolina US Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, "We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting]... we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them.

"[27] Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation in public and private facilities.

Between 1889 and 1922, as political disenfranchisement and segregation were being established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history.

Another concern for those against black suffrage was the emergence of the Populist movement in the South during the 1880s, which represented the interests of small white farmers against wealthier entities.

This movement sought a fairer distribution of wealth, reflected in demands for regulating railroad rates, establishing farmers’ cooperatives, promoting cheap money, and lowering taxes.

[35] This included secretive funding of litigation resulting in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost due to Supreme Court reluctance to interfere with states' rights.

As more Blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to battle over territory, often against Irish American communities, including in support of local political power bases.

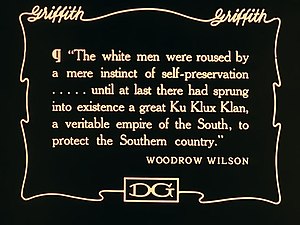

The film The Birth of a Nation (1915), which celebrated the original Ku Klux Klan, was shown at the White House to President Wilson and his cabinet members.

[40] It also controlled the governorship and a majority of the state legislature in Indiana, and exerted a powerful political influence in Arkansas, Oklahoma, California, Georgia, Oregon, and Texas.

In addition to the Great Migration and immigration from Europe, African American Army veterans, newly demobilized, sought jobs, and as trained soldiers, were less likely to acquiesce to discrimination.

[44]Similarly, Loewen argues that the family instability and crime which many sociologists have found in Black communities can be traced, not to slavery, but to the nadir and its aftermath.