The Birth of a Nation

Griffith initially claimed this was deliberate, stating "on careful weighing of every detail concerned, the decision was to have no black blood among the principals; it was only in the legislative scene that Negroes were used, and then only as 'extra people'."

Evidence exists that the film originally included scenes of white slave traders seizing blacks from West Africa and detaining them aboard a slave ship, Southern congressmen in the House of Representatives, Northerners reacting to the results of the 1860 presidential election, the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, a Union League meeting, depictions of martial law in South Carolina, and a battle sequence.

[52] At the New York premiere, Dixon spoke on stage when the interlude started halfway through the film, reminding the audience that the dramatic version of The Clansman appeared in that venue nine years previously.

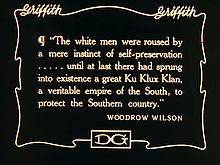

[62]: 518–519 The three title cards with quotations from Wilson's book read: "Adventurers swarmed out of the North, as much the enemies of one race as of the other, to cozen, beguile and use the negroes... [Ellipsis in the original.]

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation... until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the southern country."

[31]: 430 Dixon was alluding to the fact that Wilson, upon becoming president in 1913, had allowed cabinet members to impose segregation on federal workplaces in Washington, D.C. by reducing the number of black employees through demotion or dismissal.

We do not fear censorship, for we have no wish to offend with improprieties or obscenities, but we do demand, as a right, the liberty to show the dark side of wrong, that we may illuminate the bright side of virtue—the same liberty that is conceded to the art of the written word—that art to which we owe the Bible and the works of Shakespeare and If in this work we have conveyed to the mind the ravages of war to the end that war may be held in abhorrence, this effort will not have been in vain.Various film historians have expressed a range of views about these titles.

To Nicholas Andrew Miller, this shows that "Griffith's greatest achievement in The Birth of a Nation was that he brought the cinema's capacity for spectacle... under the rein of an outdated, but comfortably literary form of historical narrative.

One may find some flaws in the general running of the picture, but they are so small and insignificant that the bigness and greatness of the entire film production itself completely crowds out any little defects that might be singled out.

[96] The film historian Richard Schickel says that under the state's rights contracts, Epoch typically received about 10% of the box office gross—which theater owners often underreported—and concludes that "Birth certainly generated more than $60 million in box-office business in its first run".

"[105] In New York, Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise told the press after seeing The Birth of a Nation that the film was "an indescribable foul and loathsome libel on a race of human beings".

[16][107] In Washington D.C, the Reverend Francis James Grimké published a pamphlet entitled "Fighting a Vicious Film" that challenged the historical accuracy of The Birth of a Nation on a scene-by-scene basis.

[109] When Sherwin Lewis of The New York Globe wrote a piece that expressed criticism of the film's distorted portrayal of history and said that it was not worthy of constitutional protection because its purpose was to make a few "dirty dollars", Griffith responded that "the public should not be afraid to accept the truth, even though it might not like it".

[115] Critic Dolly Dalrymple wrote that, "when I saw it, it was far from silent... incessant murmurs of approval, roars of laughter, gasps of anxiety, and outbursts of applause greeted every new picture on the screen".

[110] One man viewing the film was so moved by the scene where Flora Cameron flees Gus to avoid being raped that he took out his handgun and began firing at the screen in an effort to help her.

[117] A sequel called The Fall of a Nation was released in 1916, depicting the invasion of the United States by a German-led confederation of European monarchies and criticizing pacifism in the context of the First World War.

[127] History.com states that "There is no doubt that Birth of a Nation played no small part in winning wide public acceptance" for the KKK, and that throughout the film "African Americans are portrayed as brutish, lazy, morally degenerate, and dangerous.

It's tempting to think of the film's influence as evidence of the inherent corruption of realism as a cinematic mode—but it's even more revealing to acknowledge the disjunction between its beauty, on the one hand, and, on the other, its injustice and falsehood.

But they also shouldn't lead to a denial of the peculiar, disturbingly exalted beauty of Birth of a Nation, even in its depiction of immoral actions and its realization of blatant propaganda.

Finally, Brody argued that the end of the film, where the Klan prevents defenseless African Americans from exercising their right to vote by pointing guns at them, today seems "unjust and cruel".

[130] Richard Corliss of Time wrote that Griffith "established in the hundreds of one- and two-reelers he directed a cinematic textbook, a fully formed visual language, for the generations that followed.

University of Houston historian Steven Mintz summarizes its message as follows: "Reconstruction was an unmitigated disaster, African-Americans could never be integrated into white society as equals, and the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government".

[134] The film suggested that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the postwar South, which was depicted as endangered by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North.

[135] The film is slightly less extreme than the books upon which it is based, in which Dixon misrepresented Reconstruction as a nightmarish time when black men ran amok, storming into weddings to rape white women with impunity.

[31]: 432 Bowers wrote about black empowerment that the worst sort of "scum" from the North like Stevens "inflamed the Negro's egoism and soon the lustful assaults began.

[142] Franklin wrote the film's depiction of Reconstruction as a hellish time when black freedmen ran amok, raping and killing whites with impunity until the Klan stepped in is not supported by the facts.

Building on W. E. B. DuBois' work, but also adding new sources, they focused on achievements of the African American and white Republican coalitions, such as establishment of universal public education and charitable institutions in the South and extension of voting rights to black men.

In response, the Southern-dominated Democratic Party and its affiliated white militias used extensive terrorism, intimidation and even assassinations to suppress African-American leaders and voters in the 1870s and thereby to regain power in the South.

"[145] Griffith helped to pioneer such camera techniques as close-ups, fade-outs, and a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands.

[146] I've reclaimed this title and re-purposed it as a tool to challenge racism and white supremacy in America, to inspire a riotous disposition toward any and all injustice in this country (and abroad) and to promote the kind of honest confrontation that will galvanize our society toward healing and sustained systemic change.