Chemical synapse

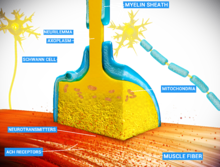

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands.

The presynaptic axon terminal, or synaptic bouton, is a specialized area within the axon of the presynaptic cell that contains neurotransmitters enclosed in small membrane-bound spheres called synaptic vesicles (as well as a number of other supporting structures and organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum).

When examined under an electron microscope, asymmetric synapses are characterized by rounded vesicles in the presynaptic cell, and a prominent postsynaptic density.

Symmetric synapses in contrast have flattened or elongated vesicles, and do not contain a prominent postsynaptic density.

Note that with the exception of the final step, the entire process may run only a few hundred microseconds, in the fastest synapses.

[14] The release of a neurotransmitter is triggered by the arrival of a nerve impulse (or action potential) and occurs through an unusually rapid process of cellular secretion (exocytosis).

[16] The fusion of a vesicle is a stochastic process, leading to frequent failure of synaptic transmission at the very small synapses that are typical for the central nervous system.

Large chemical synapses (e.g. the neuromuscular junction), on the other hand, have a synaptic release probability, in effect, of 1.

As a whole, the protein complex or structure that mediates the docking and fusion of presynaptic vesicles is called the active zone.

[17] The membrane added by the fusion process is later retrieved by endocytosis and recycled for the formation of fresh neurotransmitter-filled vesicles.

An exception to the general trend of neurotransmitter release by vesicular fusion is found in the type II receptor cells of mammalian taste buds.

The second way a receptor can affect membrane potential is by modulating the production of chemical messengers inside the postsynaptic neuron.

The nervous system exploits this property for computational purposes, and can tune its synapses through such means as phosphorylation of the proteins involved.

Homosynaptic plasticity (or also homotropic modulation) is a change in the synaptic strength that results from the history of activity at a particular synapse.

John Carew Eccles performed some of the important early experiments on synaptic integration, for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1963.

When a neurotransmitter is released at a synapse, it reaches its highest concentration inside the narrow space of the synaptic cleft, but some of it is certain to diffuse away before being reabsorbed or broken down.

[24] Recent work indicates that volume transmission may be the predominant mode of interaction for some special types of neurons.

[25] Along the same vein, GABA released from neurogliaform cells into the extracellular space also acts on surrounding astrocytes, assigning a role for volume transmission in the control of ionic and neurotransmitter homeostasis.

[13] Electrical synapses are found throughout the nervous system, including in the retina, the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, the neocortex, and in the hippocampus.

Synapses are affected by drugs, such as curare, strychnine, cocaine, morphine, alcohol, LSD, and countless others.

Strychnine blocks the inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter glycine, which causes the body to pick up and react to weaker and previously ignored stimuli, resulting in uncontrollable muscle spasms.

During the 1950s, Bernard Katz and Paul Fatt observed spontaneous miniature synaptic currents at the frog neuromuscular junction.

[33] Based on these observations, they developed the 'quantal hypothesis' that is the basis for our current understanding of neurotransmitter release as exocytosis and for which Katz received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970.

[34] In the late 1960s, Ricardo Miledi and Katz advanced the hypothesis that depolarization-induced influx of calcium ions triggers exocytosis.