Neurotransmitter

Many neurotransmitters are synthesized from simple and plentiful precursors such as amino acids, which are readily available and often require a small number of biosynthetic steps for conversion.

Neurotransmitters are generally synthesized in neurons and are made up of, or derived from, precursor molecules that are found abundantly in the cell.

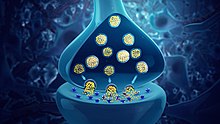

[5] Neurotransmitters are generally stored in synaptic vesicles, clustered close to the cell membrane at the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron.

However, some neurotransmitters, like the metabolic gases carbon monoxide and nitric oxide, are synthesized and released immediately following an action potential without ever being stored in vesicles.

Neurotransmitters are released into and diffuse across the synaptic cleft, where they bind to specific receptors on the membrane of the postsynaptic neuron.

[8] In order to avoid continuous activation of receptors on the post-synaptic or target cell, neurotransmitters must be removed from the synaptic cleft.

However, through histological examinations by Ramón y Cajal, a 20 to 40 nm gap between neurons, known today as the synaptic cleft, was discovered.

Upon completion of this experiment, Loewi asserted that sympathetic regulation of cardiac function can be mediated through changes in chemical concentrations.

These neurotransmitters then bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, influencing the receiving neuron in either an inhibitory or excitatory manner.

Neurotransmitter influences trans-membrane ion flow either to increase (excitatory) or to decrease (inhibitory) the probability that the cell with which it comes in contact will produce an action potential.

[20] Receptors with modulatory effects are spread throughout all synaptic membranes and binding of neurotransmitters sets in motion signaling cascades that help the cell regulate its function.

For example, it may result in an increase or decrease in sensitivity to future stimulus by recruiting more or less receptors to the synaptic membrane.

Beta-Endorphin is a relatively well-known example of a peptide neurotransmitter because it engages in highly specific interactions with opioid receptors in the central nervous system.

[citation needed] Single ions (such as synaptically released zinc) are also considered neurotransmitters by some,[40] as well as some gaseous molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

Soluble gas neurotransmitters are difficult to study, as they act rapidly and are immediately broken down, existing for only a few seconds.

The addictive opiate drugs exert their effects primarily as functional analogs of opioid peptides, which, in turn, regulate dopamine levels.

Most neuroscientists involved in this field of research believe that such efforts may further advance our understanding of the circuits responsible for various neurological diseases and disorders, as well as ways to effectively treat and someday possibly prevent or cure such illnesses.

For example, drugs used to treat patients with schizophrenia such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and clozapine are antagonists at receptors in the brain for dopamine.

An example of a receptor agonist is morphine, an opiate that mimics effects of the endogenous neurotransmitter β-endorphin to relieve pain.

Lastly, drugs can also prevent an action potential from occurring, blocking neuronal activity throughout the central and peripheral nervous system.

Cocaine, for example, blocks the re-uptake of dopamine back into the presynaptic neuron, leaving the neurotransmitter molecules in the synaptic gap for an extended period of time.

Since the dopamine remains in the synapse longer, the neurotransmitter continues to bind to the receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, eliciting a pleasurable emotional response.

Physical addiction to cocaine may result from prolonged exposure to excess dopamine in the synapses, which leads to the downregulation of some post-synaptic receptors.

After the effects of the drug wear off, an individual can become depressed due to decreased probability of the neurotransmitter binding to a receptor.

[citation needed] Prevents muscle contractions Stimulates muscle contractions Increases effects of ACh at receptors Used to treat myasthenia gravis Increases attention Reinforcing effects Prevents muscle contractions Toxic Blocks saliva production Causes sedation and depression High dose: stimulates postsynaptic receptors Blocks reuptake[45][46] Blocks reuptake Enhances attention and impulse control in ADHD Blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels Can be used as a topical anesthetic (eye drops) Prevents destruction of dopamine Alleviates hallucinations Reduces nausea and vomiting Treats depression, some anxiety disorders, and OCD[64] Common examples: Prozac and Sarafem Inhibits reuptake of serotonin Used as an appetite suppressant Stimulates 5-HT2A receptors in forebrain Causes excitatory and hallucinogenic effects Increases appetite Cognitive effects Used in smoking cessation Used in research to increase cannabinoid system activity Used in research to increase cannabinoid system activity Increases wakefulness Prevents calcium ions from entering neurons Impairs learning Impairs synaptic plasticity and certain forms of learning Induces trance-like state, helps with pain relief and sedation Ionotropic receptor Ionotropic receptor Causes seizures Increase availability of GABA Reduces the likelihood of seizures Used to study norepinephrine system Used to study norepinephrine system without affecting dopamine system An agonist is a chemical capable of binding to a receptor, such as a neurotransmitter receptor, and initiating the same reaction typically produced by the binding of the endogenous substance.

[67] Opiates, such as morphine, heroin, hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, and methadone, are μ-opioid receptor agonists; this action mediates their euphoriant and pain relieving properties.

The pharmacological effects of an antagonist, therefore, result in preventing the corresponding receptor site's agonists (e.g., drugs, hormones, neurotransmitters) from binding to and activating it.

As the concentration of antagonist increases, the binding of the agonist is progressively inhibited, resulting in a decrease in the physiological response.

Apart from recreational use, medications that directly and indirectly interact with one or more transmitter or its receptor are commonly prescribed for psychiatric and psychological issues.

Notably, drugs interacting with serotonin and norepinephrine are prescribed to patients with problems such as depression and anxiety—though the notion that there is much solid medical evidence to support such interventions has been widely criticized.