Prairie

Temperate grassland regions include the Pampas of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, and the steppe of Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan.

According to Theodore Roosevelt:We have taken into our language the word prairie, because when our backwoodsmen first reached the land [in the Midwest] and saw the great natural meadows of long grass—sights unknown to the gloomy forests wherein they had always dwelt—they knew not what to call them, and borrowed the term already in use among the French inhabitants.

[10] Humans, and grazing animals, were active participants in the process of prairie formation and the establishment of the diversity of graminoid and forbs species.

Fire has the effect on prairies of removing trees, clearing dead plant matter, and changing the availability of certain nutrients in the soil from the ash produced.

[16] The Konza Tallgrass Prairie in Kansas hosts 250 species of native plants and provides habitat for 208 birds, 27 mammals, 25 reptiles, and over 3,000 insects.

Regular controlled burning by Native Americans, practices developed through observation of non-anthropogenic fire and its effects, maintained the biodiversity of the prairie, clearing away dead vegetation and preventing trees from shading out the diverse grasses and herbaceous plants.

[19] Bison are important to the prairie ecosystem because they shape and alter the environment by grazing, trampling areas with their hooves, wallowing, and depositing manure.

In combination with severe droughts that resulted in the Dust Bowl, a major ecological disaster in which winds picked up the dry, unprotected prairie soil and formed it into "black blizzards" of airborne dirt that blackened the skies for days at a time across 19 states and forced 400,000 people to abandon the Great Plains ecoregion.

This problem was solved in 1837 by an Illinois blacksmith named John Deere who developed a steel moldboard plow that was stronger and cut the roots, making the fertile soils ready for farming.

[15] Research by David Tilman, ecologist at the University of Minnesota, suggests "Biofuels made from high-diversity mixtures of prairie plants can reduce global warming by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

"[32] Unlike corn and soybeans, which are both directly and indirectly major food crops, including livestock feed, prairie grasses are not used for human consumption.

Tilman and his colleagues estimate that prairie grass biofuels would yield 51 percent more energy per acre than ethanol from corn grown on fertile land.

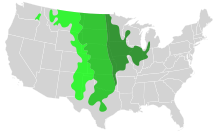

The originally treeless prairies of the upper Mississippi basin began in Indiana and extended westward and north-westward until they merged with the drier region known as the Great Plains.

The plains are 30, 50 or even 100 ft (up to 30 m) thick covering the underlying rock surface for thousands of square miles except where postglacial stream erosion has locally laid it bare.

The till is presumably made in part of preglacial soils, but it is largely composed of rock waste mechanically transported by the creeping ice sheets.

The morainic belts are arranged in groups of concentric loops, convex southward, because the ice sheets advanced in lobes along the lowlands of the Great Lakes.

Small as they are, they are the chief relief of the prairie states, and, in association with the nearly imperceptible slopes of the till plains, they determine the course of many streams and rivers, which as a whole are consequent upon the surface form of the glacial deposits.

The southernmost drift sheets, as in southern Iowa and northern Missouri, have lost their initially plain surface and are now maturely dissected into gracefully rolling forms.

Marshy sloughs still occupy the faint depressions in the till plains and the associated moraines have abundant small lakes in their undrained hollows.

Later, when the ice retreated further and the unloaded streams returned to their earlier degrading habit, they more or less completely scoured out the valley deposits, the remains of which are now seen in terraces on either side of the present flood plains.

The present site of Chicago was determined by an Indian portage or carry across the low divide between Lake Michigan and the headwaters of the Illinois River.

A very large sheet of water, named Lake Agassiz, once overspread a broad till plain in northern Minnesota and North Dakota.

Many well-defined channels, cutting across the north-sloping spurs of the plateau in the neighborhood of Syracuse, New York mark the temporary paths of the ice-bordered outlet river.

The most significant stage in this series of changes occurred when the glacio-marginal lake waters were lowered so that the long escarpment of Niagara limestone was laid bare in western New York.

high and 0.5 to 1 mile (0.80 to 1.61 kilometres) long with axes parallel to the direction of the ice motion as indicated by striae on the underlying rock floor.

A curious deposit of an impalpably fine and unstratified silt, known by the German name bess (or loess), lies on the older drift sheets near the larger river courses of the upper Mississippi basin.

Southwestern Wisconsin and parts of the adjacent states of Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota are known as the driftless zone, because, although bordered by drift sheets and moraines, it is free from glacial deposits.

Several rapids and the Saint Anthony Falls (determining the site of Minneapolis) are signs of immaturity, resulting from superposition through the drift on the under rock.

During the mechanical transportation of the till, no vegetation was present to remove the minerals essential to plant growth, as is the case in the soils of normally weathered and dissected peneplains.

The soil is similar to the Appalachian piedmont which though not exhausted by the primeval forest cover, are by no means so rich as the till sheets of the prairies.