Season

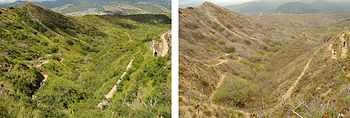

[2][3][4] In temperate and polar regions, the seasons are marked by changes in the intensity of sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface, variations of which may cause animals to undergo hibernation or to migrate, and plants to be dormant.

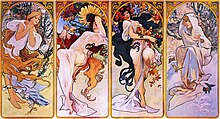

In temperate and sub-polar regions, four seasons based on the Gregorian calendar are generally recognized: spring, summer, autumn (fall), and winter.

Ecologists often use a six-season model for temperate climate regions which are not tied to any fixed calendar dates: prevernal, vernal, estival, serotinal, autumnal, and hibernal.

[citation needed] Some examples of historical importance are the ancient Egyptian seasons—flood, growth, and low water—which were previously defined by the former annual flooding of the Nile in Egypt.

In India, from ancient times to the present day, six seasons or Ritu based on south Asian religious or cultural calendars are recognised and identified for purposes such as agriculture and trade.

[5][6][7][8] Minor variation in the direction of the axis, known as axial precession, takes place over the course of 26,000 years, and therefore is not noticeable to modern human civilization.

The seasons result from the Earth's axis of rotation being tilted with respect to its orbital plane by an angle of approximately 23.4 degrees.

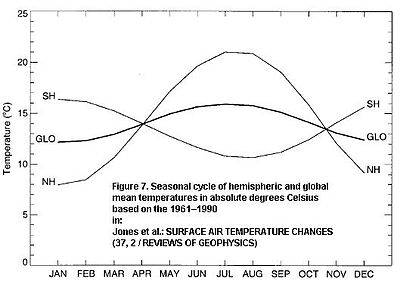

This is because during summer or winter, one part of the planet is more directly exposed to the rays of the Sun than the other, and this exposure alternates as the Earth revolves in its orbit.

For approximately half of the year (from around March 20 to around September 22), the Northern Hemisphere tips toward the Sun, with the maximum amount occurring on about June 21.

The low angle of the Sun during the winter months means that incoming rays of solar radiation are spread over a larger area of the Earth's surface, so the light received is more indirect and of lower intensity.

In the temperate and polar regions, seasons are marked by changes in the amount of sunlight, which in turn often causes cycles of dormancy in plants and hibernation in animals.

The slight differences between the solstices and the equinoxes cause seasonal shifts along a rainy low-pressure belt called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ICZ).

Calendar-based reckoning defines the seasons in relative rather than absolute terms, so the coldest quarter-year is considered winter even if floral activity is regularly observed during it, despite the traditional association of flowers with spring and summer.

Nine years before he wrote, Julius Caesar had reformed the calendar, so Varro was able to assign the dates of February 7, May 9, August 11, and November 10 to the start of spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

As noted, a variety of dates and even exact times are used in different countries or regions to mark changes of the calendar seasons.

In 1780 the Societas Meteorologica Palatina (which became defunct in 1795), an early international organization for meteorology, defined seasons as groupings of three whole months as identified by the Gregorian calendar.

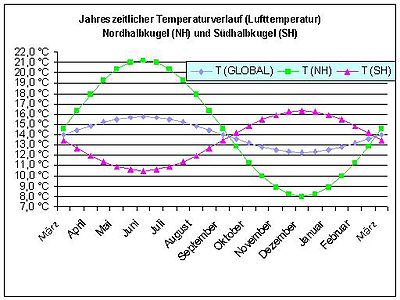

[18] According to this definition, for temperate areas in the northern hemisphere, spring begins on 1 March, summer on 1 June, autumn on 1 September, and winter on 1 December.

For the southern hemisphere temperate zone, spring begins on 1 September, summer on 1 December, autumn on 1 March, and winter on 1 June.

In Sweden and Finland, meteorologists and news outlets use the concept of thermal seasons, which are defined based on mean daily temperatures.

Currently, the most common equinox and solstice dates are March 20, June 21, September 22 or 23, and December 21; the four-year average slowly shifts to earlier times as a century progresses.

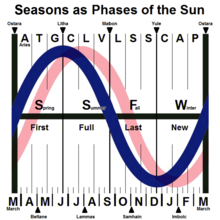

It was the method for reckoning seasons in medieval Europe, especially by the Celts, and is still ceremonially observed in Ireland and some East Asian countries.

[37] The four seasons chūn (春), xià (夏), qiū (秋), and dōng (冬)—translated as "spring", "summer", "autumn", and "winter"[38]—each center on the respective solstice or equinox.

[39] Astronomically, the seasons are said to begin on Lichun (立春, "the start of spring") on about 4 February, Lixia (立夏) on about 6 May, Liqiu (立秋) on about 8 August, and Lidong (立冬) on about 8 November.

Average dates listed here are for mild and cool temperate climate zones in the Northern Hemisphere: Indigenous people in polar, temperate and tropical climates of northern Eurasia, the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and Australia have traditionally defined the seasons ecologically by observing the activity of the plants, animals and weather around them.

Many indigenous people who no longer live directly off the land in traditional often nomadic styles, now observe modern methods of seasonal reckoning according to what is customary in their particular country or region.

For example, at the military and weather station Alert located at 82°30′05″N and 62°20′20″W, on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island, Canada (about 450 nautical miles or 830 km from the North Pole), the sun begins to peek above the horizon for minutes per day at the end of February and each day it climbs higher and stays up longer; by 21 March, the sun is up for over 12 hours.

In the weeks surrounding 21 June, in the northern polar region, the sun is at its highest elevation, appearing to circle the sky there without going below the horizon.

Seasonal reckoning in the military of any country or region tends to be very fluid and based mainly on short to medium term weather conditions that are independent of the calendar.

Thus Russia, historically navally constrained when confined to using Arkhangelsk (before the 18th century) and even Kronstadt, has particular interests in maintaining and in preserving access to Baltiysk, Vladivostok, and Sevastopol.

[48] Any modern war of manoeuvre profits from firm ground - summer can provide dry conditions suitable for marching and transport, frozen snow in winter can also offer a reliable surface for a period, but spring thaws or autumn rains can inhibit campaigning.

From bottom, clockwise:

prevernal, vernal, estival, serotinal, autumnal, hibernal