Prajnaparamita

Prajñāpāramitā practices lead to discerning pristine cognition in a self-reflexively aware way, of seeing the nature of reality.

Prajñāpāramitā is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism and is generally associated with ideas such as emptiness (śūnyatā), 'lack of svabhāva' (essence), the illusory (māyā) nature of things, how all phenomena are characterized by "non-arising" (anutpāda, i.e. unborn) and the madhyamaka thought of Nāgārjuna.

According to Edward Conze, the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras are "a collection of about forty texts ... composed somewhere on the Indian subcontinent between approximately 100 BC and AD 600.

This text also has a corresponding version in verse format, called the Ratnaguṇasaṃcaya Gāthā, which some believe to be slightly older because it is not written in standard literary Sanskrit.

[9] However, Matthew Orsborn has recently argued, based on the chiastic structures of the text that the entire sūtra may have been composed as a single whole (with a few additions added on the core chapters).

They believe that the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra originated amongst the southern Mahāsāṃghika schools of the Āndhra region, along the Kṛṣṇa River.

Comparison with the standard Sanskrit text shows that it is also likely to be a translation from Gāndhāri as it expands on many phrases and provides glosses for words that are not present in the Gāndhārī.

This points to the text being composed in Gāndhārī, the language of Gandhara (the region now called the Northwest Frontier of Pakistan, including Peshawar, Taxila and Swat Valley).

[15] The usual reason for this relative chronology which places the Vajracchedikā earlier is not its date of translation, but rather a comparison of the contents and themes.

[9] This process of expansion continued, culminating in the massive Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (100,000 lines), the largest of the PP sutras.

[24] Some of these sources, like the Svalpākṣarā, claim that simply reciting the dharanis found in the sutras are as beneficial as advanced esoteric Buddhist practices (with the full ritual panoply of mandalas and abhiseka).

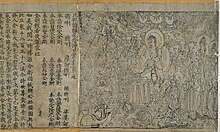

In 296, the Khotanese monk Gītamitra came to Chang'an with another copy of the same text.In China, there was extensive translation of many Prajñāpāramitā texts beginning in the second century CE.

The main translators include: Lokakṣema (支婁迦讖), Zhī Qīan (支謙), Dharmarakṣa (竺法護), Mokṣala (無叉羅), Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什, 408 CE), Xuánzàng (玄奘), Făxián (法賢) and Dānapāla (施護).

After a suite of dreams quickened his decision, Xuanzang determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, faithful to the original of 600 fascicles.

The PP sutras were first brought to Tibet in the reign of Trisong Detsen (742-796) by scholars Jinamitra and Silendrabodhi and the translator Ye shes De.

[34] The eight texts are listed according to length and are the following:[34] The Chinese scholar and translator Xuánzàng (玄奘, 602-664) is known for his translation of a massive Sanskrit collection of Prajñāpāramitā sutras called "the Xuánzàng Prajñāpāramitā Library" or "The Great Prajñāpāramitāsūtra" (般若 波羅蜜 多 經, pinyin: bōrě bōluómì duō jīng).

[35] Xuánzàng returned to China with three copies of this Sanskrit work which he obtained in South India and his translation is said to have been based on these three sources.

This collection consists of 16 Prajñāpāramitā texts:[37] A modern English translation: The Great Prajna Paramita Sutra (vols.

The dharmas that a Bodhisattva does "not stand" on include standard listings such as: the five aggregates, the sense fields (ayatana), nirvana, Buddhahood, etc.

This includes the absence, the "not taking up" (aparigṛhīta) of even "correct" mental signs and perceptions such as "form is not self", "I practice Prajñāpāramitā", etc.

According to Karl Brunnholzl, Prajñāpāramitā means that "all phenomena from form up through omniscience being utterly devoid of any intrinsic characteristics or nature of their own.

"[48] Furthermore, "such omniscient wisdom is always nonconceptual and free from reference points since it is the constant and panoramic awareness of the nature of all phenomena and does not involve any shift between meditative equipoise and subsequent attainment.

[51] Another quality of the Bodhisattva is their freedom from fear (na vtras) in the face of the seemingly shocking doctrine of the emptiness of all dharmas which includes their own existence.

The Prajñāpāramitā sutras also mention that bodhicitta is a middle way, it is neither apprehended as existent (astitā) or non-existent (nāstitā) and it is "immutable" (avikāra) and "free from conceptualization" (avikalpa).

"[54] Bodhisattvas and Mahāsattvas are also willing to give up all of their meritorious deeds for sentient beings and develop skillful means (upaya) in order to help abandon false views and teach them the Dharma.

[56]Suchness then does not come or go because like the other terms, it is not a real entity (bhūta, svabhāva), but merely appears conceptually through dependent origination, like a dream or an illusion.

[57] Most modern Buddhist scholars such as Lamotte, Conze and Yin Shun have seen Śūnyatā (emptiness, voidness, hollowness) as the central theme of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras.

The Mahayana understands it to mean that dharmas are empty of any own-being, i.e.,that they are not ultimate facts in their own right, but merely imagined and falsely discriminated, for each and every one of them is dependent on something other than itself.

[61] The Prajñāpāramitā sutras commonly state that all dharmas (phenomena), are in some way like an illusion (māyā), like a dream (svapna) and like a mirage.