Prayer rug

[3] Among Russian Orthodox Christians, particularly Old Ritualists, a special prayer rug known as the Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.

For Muslims, when praying, a niche, representing the mihrab of a mosque, at the top of the mat must be pointed to the Islamic center for prayer, Mecca.

[3] Additionally, carpets cover the floors of parishes in denominations such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church on which Christians prostrate in prayer.

[8] Among Russian Orthodox Old Ritualists, a special prayer rug known as the Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.

[14][15] While not explicitly mandated in the Quran or Ḥadīt̲h, prayer rugs, known in one source as sad̲j̲d̲j̲āda,[16] are nonetheless deeply embedded in Islamic practice and material culture.

They represent a physical and symbolic delineation of sacred space, allowing the worshiper to create a ritually pure area for prayer.

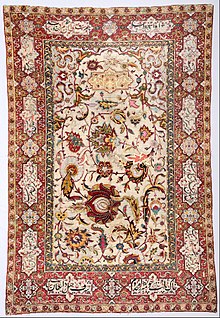

[17][16] Prayer rugs, particularly those from the Safavid and Qajar periods, offer a window into broader cultural and intellectual trends in the Islamic world.

[18] Ultimately, the prayer rug, while a simple object in form, embodies the connection between the material and the spiritual, the individual and the communal, and historical trends and artistic expression in the Islamic world.

[22] During prayer, the individual kneels at the base of the rug and performs sud̲j̲ūd, prostrating with their forehead, nose, hands, knees, and toes touching the ground, towards the niche representing the direction of Mecca.

[26] The oldest surviving prayer rugs, discovered in mosques in Konya and Beyşehir, are believed to be from the 14th century, and were woven entirely of wool with geometric designs.

The 18th-century cotton prayer rugs from Bīd̲j̲āpūr, with their floral patterns and uniquely Indian domed minarets rising from the miḥrāb, show this cultural fusion.

[27] The Saxon Lutheran Churches, parish storerooms and museums of Transylvania safeguard about four hundred Anatolian rugs, dating from the late-15th to early 18th century.

By contrast, following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, part of Hungary was designated a Pashalik and was under Turkish occupation for over a century and a half.

Frescoes were white-washed or destroyed, and the many sumptuous winged altar-pieces were removed maintaining exclusively the main altar piece.

[citation needed] In this situation the Oriental rugs, created in a world that was spiritually different from Christianity, found their place in the Reformed churches which were to become their main custodians.

The removal from the commercial circuit and the fact that they were used to decorate the walls, the pews and the balconies but not on the floor was crucial for their conservation over the years.

The last decades of the 17th century marked a decline of the rug trade between Transylvania and Turkey which affected the carpet production in Anatolia.