Pre-Columbian woodlands of North America

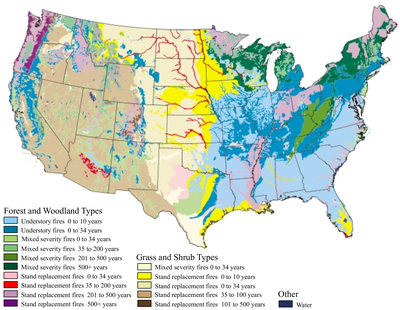

Pre-Columbian woodlands of North America, consisting of a mixed woodland-grassland ecosystem, were maintained by both natural lightning fires and by Native Americans before the significant arrival of Europeans.

[1][2][3][4] Although decimated by widespread epidemic disease, Native Americans in the 16th century continued using fire to clear woodlands until European colonists began colonizing the eastern seaboard.

Pre-existing natural communities remained largely intact south of the glaciers, but saw an increase in dominance of pine and a now-extinct species of temperate spruce, (Picea critchfieldii).

When the glaciers began to retreat, the ancient natural communities of the southeast would be the primary source of colonization for the newly exposed areas in the midwest.

Intentional burning of vegetation was taken up to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories, thereby making travel easier and facilitating the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants that were important for both food and medicines.

[7] From the 16th century on, the massive depopulation of Native Americans caused by the arrival of European settlers meant an end to burning and farming across large areas.

Lightning and humans burned the understory of longleaf pine every 1 to 15 years from Archaic periods until widespread fire suppression practices were adopted in the 1930s.

[1][11][12] By the latter half of the 20th century, many researchers had rediscovered both the prehistoric use of fire and methods to practice burning, but by then almost all prairie and grassy woodlands had been converted to agriculture or succeeded to full-canopy forest.