Missouri River

More than ten major groups of Native Americans populated the watershed, with most leading a nomadic lifestyle and dependent on enormous bison herds that roamed through the Great Plains.

[24] With more than 170,000 square miles (440,000 km2) under the plow, the Missouri River watershed includes roughly one-fourth of all the agricultural land in the United States, providing more than a third of the country's wheat, flax, barley, and oats.

[17] The Missouri's drainage basin has highly variable weather and rainfall patterns, Overall, the watershed is defined by a continental climate with warm, wet summers and harsh, cold winters.

[49] Among rivers of North America as a whole, the Missouri is thirteenth largest, after the Mississippi, Mackenzie, St. Lawrence, Ohio, Columbia, Niagara, Yukon, Detroit, St. Clair, Fraser, Slave, and Koksoak.

[7] The Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana at the headwaters of the Missouri River first rose in the Laramide Orogeny, a mountain-building episode that occurred from around 70 to 45 million years ago (the end of the Mesozoic through the early Cenozoic).

[63][64][65] This Laramide uplift caused the sea to retreat and laid the framework for a vast drainage system of rivers flowing from the Rocky and Appalachian Mountains, the predecessor of the modern-day Mississippi watershed.

The lowest major Cenozoic unit, the White River Formation, was deposited between roughly 35 and 29 million years ago[70][71] and consists of claystone, sandstone, limestone, and conglomerate.

[75] Immediately before the Quaternary Ice Age, the Missouri River was likely split into three segments: an upper portion that drained northwards into Hudson Bay,[76][77] and middle and lower sections that flowed eastward down the regional slope.

As the lakes rose, the water in them often spilled across adjacent local drainage divides, creating now-abandoned channels and coulees including the Shonkin Sag, 100 miles (160 km) long.

According to the writings of early colonists, some of the major tribes along the Missouri River included the Otoe, Missouria, Omaha, Ponca, Dakota, Lakota, Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Assiniboine, Gros Ventres and Blackfeet.

[91] A large cluster of walled Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara villages situated on bluffs and islands of the river was home to thousands, and later served as a market and trading post used by early French and British explorers and fur traders.

[102] Bourgmont had in fact been in trouble with the French colonial authorities since 1706, when he deserted his post as commandant of Fort Detroit after poorly handling an attack by the Ottawa that resulted in thirty-one deaths.

However, this ended after news of incursions by trappers working for the Hudson's Bay Company in the upper Missouri River watershed was brought back following an expedition by Jacques D'Eglise in the early 1790s.

At the Mandan villages in North Dakota, they forcefully expelled several British traders, and while talking to the populace they pinpointed the location of the Yellowstone River, which was called Roche Jaune ("Yellow Rock") by the French.

[108][110] In 1795, the young United States and Spain signed Pinckney's Treaty, which recognized American rights to navigate the Mississippi River and store goods for export in New Orleans.

Despite the demise of the once-prosperous trade, however, its legacy led to the opening of the American West and a flood of settlers, farmers, ranchers, adventurers, hopefuls, financially bereft, and entrepreneurs took their place.

[128] The river roughly defined the American frontier in the 19th century, particularly downstream from Kansas City, where it takes a sharp eastern turn into the heart of the state of Missouri, an area known as the Boonslick.

An early expedition led by Robert Stuart from 1812 to 1813 proved the Platte impossible to navigate by the dugout canoes they used, let alone the large sidewheelers and sternwheelers that would later ply the Missouri in increasing numbers.

This resulted in frequent raids, massacres and armed conflicts, leading to the federal government creating multiple treaties with the Plains tribes, which generally involved establishing borders and reserving lands for the indigenous.

[137][138] Conflicts between natives and settlers over the opening of the Bozeman Trail in the Dakotas, Wyoming and Montana led to Red Cloud's War, in which the Lakota and Cheyenne fought against the U.S. Army.

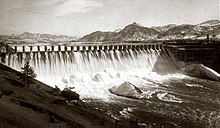

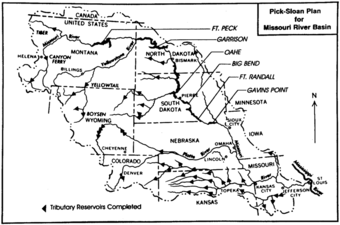

[156] However, Fort Peck only controls runoff from 11 percent of the Missouri River watershed, and had little effect on a severe snowmelt flood that struck the lower basin three years later.

[163] The flooding of lands along the Missouri River heavily impacted Native American groups whose reservations included fertile bottomlands and floodplains, especially in the arid Dakotas where it was some of the only good farmland they had.

In the early decades before man controlled the river's flow, its sketchy rises and falls and its massive amounts of sediment, which prevented a clear view of the bottom, wrecked some 300 vessels.

The large reservoirs of the Mainstem System help provide a dependable flow to maintain the navigation channel year-round, and are capable of halting most of the river's annual freshets.

The Upper Missouri, roughly encompassing the area within Montana, Wyoming, southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, and North Dakota, comprises mainly semiarid shrub-steppe grasslands with sparse biodiversity because of Ice Age glaciations.

[211] The Middle Missouri ecoregion, extending through Colorado, southwestern Minnesota, northern Kansas, Nebraska, and parts of Wyoming and Iowa, has greater rainfall and is characterized by temperate forests and grasslands.

Because of the low use of the shipping channel in the lower Missouri maintained by the USACE, it is now considered feasible to remove some of the levees, dikes, and wing dams that constrict the river's flow, thus allowing it to naturally restore its banks.

[223][224] These reaches exhibit islands, meanders, sandbars, underwater rocks, riffles, snags, and other once-common features of the lower river that have now disappeared under reservoirs or have been destroyed by channeling.

[227][228] In north-central Montana, some 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) along over 125 miles (201 km) of the Missouri River, centering on Fort Peck Lake, comprise the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge.

[229] The wildlife refuge consists of a native northern Great Plains ecosystem that has not been heavily affected by human development, except for the construction of Fort Peck Dam.