Precipitation hardening

Precipitation hardening relies on changes in solid solubility with temperature to produce fine particles of an impurity phase, which impede the movement of dislocations, or defects in a crystal's lattice.

Unlike ordinary tempering, alloys must be kept at elevated temperature for hours to allow precipitation to take place.

Precipitation heat treating involves the addition of impurity particles to increase a material's strength.

[1] This technique exploits the phenomenon of supersaturation, and involves careful balancing of the driving force for precipitation and the thermal activation energy available for both desirable and undesirable processes.

Nucleation occurs at a relatively high temperature (often just below the solubility limit) so that the kinetic barrier of surface energy can be more easily overcome and the maximum number of precipitate particles can form.

This is carried out under conditions of low solubility so that thermodynamics drive a greater total volume of precipitate formation.

Diffusion's exponential dependence upon temperature makes precipitation strengthening, like all heat treatments, a fairly delicate process.

Precipitation strengthening is possible if the line of solid solubility slopes strongly toward the center of a phase diagram.

While a large volume of precipitate particles is desirable, a small enough amount of the alloying element should be added so that it remains easily soluble at some reasonable annealing temperature.

A large number of other constituents may be unintentional, but benign, or may be added for other purposes such as grain refinement or corrosion resistance.

An example is the addition of Sc and Zr to aluminum alloys to form FCC L12 structures that help refine grains and strengthen the material.

[3] The addition of large amounts of nickel and chromium needed for corrosion resistance in stainless steels means that traditional hardening and tempering methods are not effective.

However, precipitates of chromium, copper, or other elements can strengthen the steel by similar amounts in comparison to hardening and tempering.

For instance, some aluminium alloys used to make rivets for aircraft construction are kept in dry ice from their initial heat treatment until they are installed in the structure.

After this type of rivet is deformed into its final shape, ageing occurs at room temperature and increases its strength, locking the structure together.

What differentiates this mechanism from solid solution strengthening is the fact that the precipitate has a definite size, not an atom, and therefore a stronger interaction with dislocations.

Chemical strengthening is associated with the surface energy of the newly introduced precipitate-matrix interface when the particle is sheared by dislocations.

Another way to consider this mechanism is that when a dislocation shears a particle, the stacking sequence between the new surface made and the matrix is broken, and the bonding is not stable.

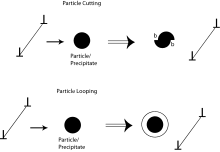

The main mechanism therefore is Orowan strengthening, where the strong particles do not allow for dislocations to move past.

These lattice distortions result when the precipitate particles differ in size and crystallographic structure from the host atoms.

Consequently, there is a negative interaction energy between a dislocation and a precipitate that each respectively cause a compressive and a tensile stress or vice versa.

Due to the difference in lattice parameters of the two phases, a coherency strain energy is associated with this type of boundary.

Dislocation bowing, also called Orowan strengthening,[8] is more likely to occur when the particle density in the material is lower.

This governing equation shows that for dislocation bowing the strength is inversely proportional to the second phase particle radius

[11] While significant effort has been made to develop new alloys, the experimental results take time and money to be implemented.

[15] In this way, some researchers have developed strategies to screen the possible strengthening precipitates that allow decreasing the weight of some metal alloys.

[16] For example, Mg-alloys have received progressive interest to replace Aluminum and Steel in the vehicle industry because it is one of the lighter structural metals.

To overcome this, the Precipitation hardening technique, through the addition of rare earth elements, has been used to improve the alloy strength and ductility.

Specifically, the LPSO structures were found that are responsible for these increments, generating an Mg-alloy that exhibited high-yield strength: 610 MPa at 5% of elongation at room temperature.

[17] In this way, some researchers have developed strategies to Looking for cheaper alternatives than Rare Elements (RE) it was simulated a ternary system with Mg-Xl-Xs, where Xl and Xs correspond to atoms larger than and shorter than Mg, respectively.