Pre-dreadnought battleship

New naval powers such as Germany, Japan, the United States, and to a lesser extent Italy and Austria-Hungary, began to establish themselves with fleets of pre-dreadnoughts.

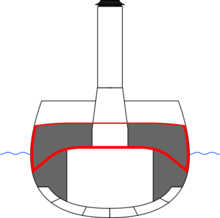

Devastation was the first ocean-going breastwork monitor; although her very low freeboard, meant that her decks were subject to being swept by water and spray, interfering with the working of her guns.

[5] Navies worldwide continued to build masted, turretless battleships which had sufficient freeboard and were seaworthy enough to fight on the high seas.

Equipped with breech-loading guns of between 12-inch and 16 ¼-inch (305-mm and 413-mm) caliber, the Admirals continued the trend of ironclad warships mounting gigantic weapons.

[6] The subsequent Royal Sovereign class of 1889 retained barbettes but were uniformly armed with 13.5-inch (343 mm) guns; they were also significantly larger (at 14,000 tons displacement) and faster (because of triple-expansion steam engines) than the Admirals.

The introduction of slow-burning nitrocellulose and cordite propellant allowed the employment of a longer barrel, and therefore higher muzzle velocity—giving greater range and penetrating power for the same caliber of shell.

A medium-caliber gun could be expected to penetrate the light armor of smaller ships, while the rate of fire of the secondary battery was important in scoring a hit against a small, maneuvrable target.

The United States Navy pioneered the intermediate battery concept in the Indiana, Iowa, and Kearsarge classes, but not in the battleships laid down between 1897 and 1901.

[16] Shortly after the USN re-adopted the intermediate battery, the British, Italian, Russian, French, and Japanese navies laid down intermediate-battery ships.

[17] Pre-dreadnought battleships carried a considerable weight of steel armor, providing them with effective defense against the great majority of naval guns in service during the period.

Yet the emergence of the quick-firing gun and high explosives in the 1880s meant that the 1870s to early 1880s concept of the pure central citadel was also inadequate in the 1890s and that thinner armor extensions towards the extremities would greatly aid the ship's defensive qualities.

The majority of battleships during this period of construction were fitted with a heavily-armored conning tower, or CT, which was intended for the use of the command staff during battle.

This was protected by a vertical, full height, ring of armor nearly equivalent in thickness to the main battery gunhouses and provided with observation slits.

A narrow armored tube extended down below this to the citadel; this contained & protected the various voice-tubes used for communication from the CT to various key stations during battle.

France and Germany preferred the three-screw approach, which allowed the engines to be shorter and hence more easily protected; they were also more maneuverable and had better resistance to accidental damage.

The Royal Navy remained the world's largest fleet, though both Britain's traditional naval rivals and the new European powers increasingly asserted themselves against its supremacy.

[33] Counting two ships ordered by Chile but taken over by the British, the Royal Navy had 50 pre-dreadnought battleships ready or being built by 1904, from the 1889 Naval Defence Act's ten units onwards.

[34] The Jeune École retained a strong influence on French naval strategy, and by the end of the 19th century France had abandoned competition with Britain in battleship numbers.

[36] This increase was due to the determination of the navy chief Alfred von Tirpitz and the growing sense of national rivalry with the UK.

[39] The Austro-Hungarian Empire also saw a naval renaissance during the 1890s, though of the nine pre-dreadnought battleships ordered only the three of the Habsburg class arrived before Dreadnought made them obsolete.

[16] Nevertheless, it was these earlier ships that ensured American naval dominance against the antiquated Spanish fleet—which included no pre-dreadnoughts—in the Spanish–American War, most notably at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba.

Dreadnoughts and battlecruisers were believed vital for the decisive naval battles which at the time all nations expected, hence they were jealously guarded against the risk of damage by mines or submarine attack, and kept close to home as much as possible.

While two German cruisers menaced British shipping, the Admiralty insisted that no battlecruisers could be spared from the main fleet and sent to the other side of the world to deal with them.

Intended to stiffen the British cruisers in the area, in fact her slow speed meant that she was left behind at the disastrous Battle of Coronel.

[47] In the Black Sea five Russian pre-dreadnoughts saw brief action against the Ottoman battlecruiser Yavuz Sultan Selim during the Battle of Cape Sarych in November 1914.

[49] The principle that disposable pre-dreadnoughts could be used where no modern ship could be risked was affirmed by British, French and German navies in subsidiary theatres of war.

[51] In return, a pair of Ottoman pre-dreadnoughts, the ex-German Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin, bombarded Allied forces during the Gallipoli campaign until the latter was torpedoed and sunk by a British submarine in 1915.

Germany, which lost most of its fleet under the terms of the Versailles treaty, was allowed to keep eight pre-dreadnoughts (of which only six could be in active service at any one time) which were counted as armored coast-defense ships;[58] two of these were still in use at the beginning of World War II.

One of these, Schleswig-Holstein, shelled the Polish Westerplatte peninsula, opening the German invasion of Poland and firing the first shots of the Second World War.

[64] There is only one pre-dreadnought preserved today: the Imperial Japanese Navy's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima, Mikasa, which is now located in Yokosuka, where she has been a museum ship since 1925.