History of early Tunisia

The first meeting of Phoenician and Berber occurred well to the east of Tunisia, well before the rise of Carthage: a tenth-century invasion of Phoenicia was led by a pharaoh of the Berbero-Libyan dynasty (the XXII) of Ancient Egypt.

Evidence comes from various artifacts, settlement and burial sites, inscriptions, and historical writings; supplementary views are derived by disciplines studying genetics and linguistics.

Evidence of habitation in the North African region by human ancestors has been found stretching back one or two million years, yet not to rival those most-ancient finds in south and east Africa.

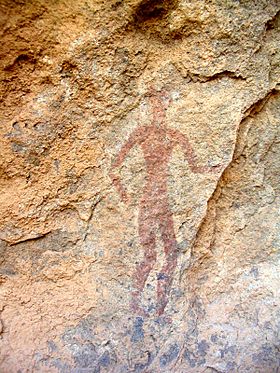

The evidence of the art and expressive artifacts dating back about 10 to 12 kya show a new sophistication in handling experience, perhaps being the fruits of prior advances in the articulation of symbols and language.

[14] Saharan rock art, the inscriptions and the paintings that show various design patterns as well as figures of animals and of humans, are attributed to the Berbers and also to black Africans from the south.

Among the animals depicted, alone or in staged scenes, are large-horned buffalo (the extinct bubalus antiquus), elephants, donkeys, colts, rams, herds of cattle, a lion and lioness with three cubs, leopards or cheetahs, hogs, jackles, rhinoceroses, giraffes, hippopotamus, a hunting dog, and various antelope.

The other four branches of Afroasiatic are: Ancient Egyptian, Semitic (which includes Akkadian, Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, and Amharic), Cushitic (around the Horn and the lower Red Sea),[46] and Chadic (e.g., Hausa).

The Afroasiatic language family has great diversity among its member idioms and a corresponding antiquity in time depth,[47][48] both as to the results of analyses in historical linguistics and as regards the seniority of its written records, composed using the oldest of writing systems.

[52][53] Earlier academic speculation as to the prehistoric homeland of Afroasiatic and its geographic spread centered on a source in southwest Asia,[54][55][56] but more recent work in the various related disciplines has focused on Africa.

Meanwhile, the peoples who spoke proto-Berbero-Libyan spread out westward across North Africa, along the Mediterranean coast and into a Sahara region then better watered, traveling in a centuries-long migration until reaching the Atlantic and its offshore islands.

[67] Hence the proto Semitic speakers probably left the common Afroasiatic community earlier, by ten kya (thousand years ago), starting from an area nearby a more fruitful Sinai.

Earlier, at the long-occupied cave of Haua Fteah in Cyrenaica, "food gatherers with a Caspian flint industry were succeeded by stock breeders with pottery.

"[71] Material culture progressed, resulting in the Neolithic Revolution with its animal domestication and agriculture advances; craft techniques included imprinted pottery, and finely chipped stone implements (evolved from earlier arrowheads).

Ceramic bowls and basins, goblets, large plates, as well as dishes raised by a central column, were domestic items in daily use, sometimes hung up on the wall.

[74] From physical evidence unearthed in Tunisia archaeologists present the Berbers as already "farmers with a strong pastoral element in their economy and fairly elaborate cemeteries", well over a thousand years before the Phoenicians arrived to found Carthage.

[75] Apparently, prior to written records about them, sedentary rural Berbers lived in semi-independent farming villages, composed of small, composite, tribal units under a local leader who worked to harmonize its clans.

Modern conjecture is that feuding between neighborhood clans at first impeded organized political life among these ancient Berber farmers, so that social coordination did not develop beyond the village level, whose internal harmony could vary.

[78] Tribal authority was strongest among the wandering pastoralists, much weaker among the agricultural villagers, and would later attenuate further with the advent of cities connected to strong commercial networks and foreign polities.

Eventually Carthage and its sister city-states would inspire Berber villages to join in order to marshall large-scale armies, which naturally called forth strong, centralizing leadership.

[83] Mommsen, a widely admired historian of the 19th century, stated: "They call themselves in the Riff near Tangier Amâzigh, in the Sahara Imôshagh, and the same name meets us, referred to particular tribes, on several occasions among the Greeks and Romans, thus as Maxyes at the founding of Carthage, as Mazices in the Roman period at different places in the Mauretanian north coast; the similar designation that has remained with the scattered remnants proves that this great people has once had a consciousness, and has permanently retained the impression, of the relationship of its members.

[87] Berbers together, with their relations and descendants, have been the major population group to inhabit the Maghrib (North African apart from the Nile) since about eight kya (thousand years ago).

Egyptian hieroglyphs from early dynasties testify to Libyans, who were the Berbers of Egypt's "western desert"; they are first mentioned directly as the "Tehenou" during the pre-dynastic reigns of Scorpion (c. 3050) and of Narmer (on an ivory cylinder).

[95] Tombs of the 13th century contain paintings of Libu leaders wearing fine robes, with ostrich feathers in their "dreadlocks", short pointed beards, and tattoos on their shoulders and arms.

[102] Hence during the classical era of the Mediterranean, all of the Berber peoples of North Africa were often collectively called Libyans, due to the fame first won by the Meshwesh dynasty of Egypt.

[103][104][105] West of the Meshwesh dynasty of Egypt, later reports of foreigners mention more rustic Berber people by the Mediterranean, living in fertile and accessible coastal regions.

[109] During the 5th century BC, the Greek writer Herodotus (c.490-425) mentions Berbers as mercenaries of Carthage with regard to specific military events in Sicily, circa 480.

[114][115] In the 4th century, Berber kingdoms are referenced, e.g., the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus evidently mentions the Libyo-Berber king Aelymas, a neighbor to the south of Carthage, who dealt with the invader Agathocles (361-289), a Greek ruler from Sicily.

[125][126] The supernatural could reside in the waters, in trees, or come to rest in unusual stones (to which the Berbers would apply oils); such power might inhabit the winds (the Sirocco being formidable across North Africa).

[140] George Aaron Barton suggested that the prominent goddess of Carthage Tanit originally was a Berbero-Libyan deity whom the newly arriving Phoenicians sought to propitiate by their worship.

[143][144][145] From linguistic evidence Barton concluded that before developing into an agricultural deity, Tanit probably began as a goddess of fertility, symbolized by a tree bearing fruit.