History of Uzbekistan

The first people recorded in Central Asia were Scythians who came from the northern grasslands of what is now Uzbekistan, sometime in the first millennium BC; when these nomads settled in the region they built an extensive irrigation system along the rivers.

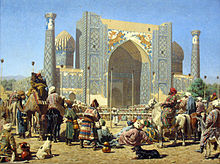

As a result of this trade on what became known as the Silk Route, Bukhara, Samarkand and Khiva eventually became extremely wealthy cities, and at times Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) was one of the most influential and powerful Persian provinces of antiquity.

This period saw leading figures of the Islamic Golden Age, including Muhammad al-Bukhari, Al-Tirmidhi, al Khwarizmi, al-Biruni, Avicenna and Omar Khayyam.

In the seventh century AD, the Soghdian Iranians, who profited most visibly from this trade, saw their province of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) overwhelmed by Arabs, who spread Islam throughout the region.

Because of this trade on what became known as the Silk Route, Bukhara and Samarqand eventually became extremely wealthy cities, and at times Transoxiana was one of the most influential and powerful Persian provinces of antiquity.

The Arabs, on the other hand, were led by a brilliant general, Qutaybah ibn Muslim, and were also highly motivated by the desire to spread their new faith (the official beginning of which was in AD 622).

[13][full citation needed] Despite brief Arab rule, Central Asia successfully retained much of its Iranian characteristic, remaining an important center of culture and trade for centuries after the adoption of the new religion.

Some of the greatest historians, scientists, and geographers in the history of Islamic culture were natives of the region including al-Bukhari, Al-Tirmidhi, al Khwarizmi, al-Biruni, Avicenna and Omar Khayyam.

In the late tenth century, as the Samanids began to lose control of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) and northeastern Iran, some of these soldiers came to positions of power in the government of the region, and eventually established their own states, albeit highly Persianized.

The Ghaznavid state, which captured the Samanid domains south of the Amu Darya, was able to conquer large areas of eastern Iran, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan during the reign of Sultan Mahmud.

[17] The Seljuks dominated a wide area from Asia Minor, Iran, Iraq, and parts of the Caucasus, to the western sections of Transoxiana, in Afghanistan, in the eleventh century.

In the early fourteenth century, however, as the empire began to break up into its constituent parts, the Chaghtai territory also was disrupted as the princes of various tribal groups competed for influence.

Near the end of the sixteenth century, the Uzbek states of Bukhara and Khorazm began to weaken because of their endless wars against each other and the Persians and because of strong competition for the throne among the khans in power and their heirs.

The era of Russian rule did produce important social and economic changes for some Uzbeks as a new middle class developed and some peasants were affected by the increased emphasis on cotton cultivation.

The policy of the Russian authorities (refusal to approve waqf documents) resulted in the fall of incomes and the level of living standards in Islamic "sacred families".

The territory of Uzbekistan was divided into three political groupings: the khanates of Bukhara and Khiva and the Guberniya (Governorate General) of Turkestan, the last of which was under direct control of the Ministry of War of Russia.

In 1905 the unexpected victory of a new Asiatic power in the Russo-Japanese War and the eruption of revolution in Russia raised the hopes of reform factions that Russian rule could be overturned, and a modernization program initiated, in Central Asia.

The democratic reforms that Russia promised in the wake of the revolution gradually faded, however, as the tsarist government restored authoritarian rule in the decade that followed 1905.

Nevertheless, some of the future leaders of Soviet Uzbekistan, including Abdur Rauf Fitrat and others, gained valuable revolutionary experience and were able to expand their ideological influence in this period.

In February the revolutionary events in Russia's capital, Petrograd (St. Petersburg), were quickly repeated in Tashkent, where the tsarist administration of the governor general was overthrown.

Following the suppression of autonomy in Quqon, Jadidists and other loosely connected factions began what was called the Basmachi revolt against Soviet rule, which by 1922 had survived the civil war and was asserting greater power over most of Central Asia.

The indigenous leaders cooperated closely with the communist government in enforcing policies designed to alter the traditional society of the region: the emancipation of women, the redistribution of land, and mass literacy campaigns.

[28] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Jadidist movement of educated Central Asians, centered in present-day Uzbekistan, began to advocate overthrowing Russian rule.

In the late 1930s, Khojayev and the entire leadership of the Uzbek Republic were purged and executed by Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin (in power 1927–53) and replaced by Russian officials.

During the war years, in addition to the Russians who moved to Uzbekistan, other nationalities such as Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and Koreans were exiled to the republic because Moscow saw them as subversive elements in European Russia.

[29] Following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, the relative relaxation of totalitarian control initiated by First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev (in office 1953–64) brought the rehabilitation of some of the Uzbek nationalists who had been purged.

As became apparent after his death, Rashidov's strategy had been to remain a loyal ally of Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982, by bribing high officials of the central government.

Other grievances included discrimination and persecution experienced by Uzbek recruits in the Soviet army and the lack of investment in industrial development in the republic to provide jobs for the ever-increasing population.

Uzbekistan's image in the West alternated in the ensuing years between an attractive, stable experimental zone for investment and a post-Soviet dictatorship whose human rights record made financial aid inadvisable.

Human rights activists reported various cases of multiple voting throughout the country as well as official pressure on voters at polling stations to cast ballots for Karimov.