Preorbital gland

[8] In juvenile red deer (Cervus elaphus), the preorbital gland appears to play a role in the response to stress.

[12] The bovids (family Bovidae) comprise some 140 species of ruminants in which at least the males bear unbranched, hollow horns covered in a permanent sheath of keratin.

[14] Caprids (dwarf antelope, such as the sheep, goats, muskox, serows, gorals, and several similar species) use their preorbital glands to establish social rank.

By sending and receiving olfactory cues, this behavior appears to be a means of establishing dominance and of avoiding a fight, which would otherwise involve potentially injurious butting or clashing with the forehead.

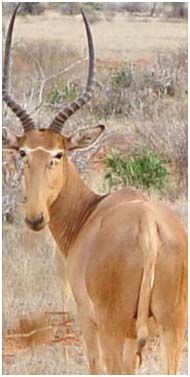

[15] The antilopine bovids (dwarf antelope, such as the springbok, blackbuck, gazelles, dik-diks, oribi, and several similar species) have well-developed preorbital glands.

[3] Among the cephalophines, members of the Philantomba and Sylvicapra genera are all solitary animals which display territorial behavior and have well-developed preorbital glands.

Two thiazole compounds and an epoxy ketone are present in significantly higher concentrations in male than in female secretions, suggesting that they could serve as sex recognition cues.

[17] The alcephine bovids (wildebeests, hartebeests, hirola, bontebok, blesbok, and several similar species) have preorbital glands which secrete complex mixtures of chemical compounds.

For example, Günther's dik-dik (Madoqua guentheri) is a monogamous species of antelope that lives in a permanent territory, the boundaries of which the animals mark several times a day by actively pressing the preorbital glands to grasses and low-lying plants and applying the secretions.

The glands are located in large preorbital pits in the lacrimal bone, and are surrounded by specialized facial muscles that compress them to express the secretions more effectively.

[20] The recent identification of several antimicrobial compounds from the secretions of animal dermal scent glands may be the beginning of a promising new area of drug development.

Assuming functional analogs of these lead compounds can be synthesized and found to be effective in vivo, the potential exists for producing new antimicrobial agents against pathogenic skin microorganisms.