Presidency of Andrew Johnson

In April 1866, he nominated Henry Stanbery to fill the Supreme Court vacancy left by the death of Associate Justice John Catron, but Congress eliminated the seat by passing the Judicial Circuits Act of 1866.

In late May, the final Confederate force in the field surrendered, and Johnson presided over a triumphant military parade in Washington, D.C. alongside the cabinet and the nation's top generals.

[32] The Moderate Republicans were not as enthusiastic about the idea of African-American suffrage as their Radical colleagues, either because of their own local political concerns, or because they believed that the freedman would be likely to cast his vote badly.

Despite the pleas of African-Americans and many congressional Republicans, Johnson viewed suffrage as a state issue, and was uninterested in using federal power to impose sweeping changes on the defeated South.

[38] Alabama Governor Lewis E. Parsons, a Johnson appointee, declared that "every political right which the state possessed under the federal Constitution is hers today, with the single exception relating to slavery.

[47] Johnson's 1865 program of presidential reconstruction extinguished any hope of enforcing black suffrage in the aftermath of the Civil War, as re-empowered Southern whites were no longer willing to accept sweeping changes to the pre-war status quo.

[58][59] When called upon by the crowd to say who they were, Johnson named Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and accused them of plotting his assassination.

Though most of Johnson's cabinet urged him to sign the Civil Rights Act, the president vetoed it, marking a permanent break with the moderate faction of the Republican Party.

The trip, including speeches in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis and Columbus, proved politically disastrous, as the president made controversial comparisons between himself and Christ and engaged in arguments with hecklers.

Johnson also vetoed legislation admitting Colorado Territory to the Union, but Congress failed to override it, as enough senators agreed that a district with a population of only 30,000 was not yet worthy of statehood.

[80] This refusal prompted Congressman Thaddeus Stevens to introduce legislation to dissolve the Southern state governments and reconstitute them into five military districts, under martial law.

Though Johnson retained the power to command and undermine the army and the Freedmen's Bureau, the First Reconstruction Act asserted Congress's ability to protect the rights of African Americans and prevent ex-Confederates from re-establishing political dominance.

No seats in Congress were directly elected in the polling, but the Democrats took control of the Ohio General Assembly, allowing them to defeat for re-election one of Johnson's strongest opponents, Senator Benjamin Wade.

Seven Republicans—Senators Grimes, Ross, Trumbull, William Pitt Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, John B. Henderson, and Peter G. Van Winkle—joined their Democratic colleagues in voting to acquit the president.

As Radical Republicans feared that these Southern states would deny African-Americans the right to vote in 1868 or future elections, they also drafted what would become the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibited the restriction of suffrage on the basis of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

This time, however, an amendment sponsored by Senator George F. Edmunds effectively conditioned statehood on the acceptance by the territory of a prohibition against voting restrictions based on race or color.

[citation needed] By 1867, the Russian government saw its North American colony (today Alaska) as a financial liability, and feared eventually losing it if a war broke out with Britain.

[132] Although ridiculed in some quarters as "Seward's Folly," American public opinion was generally quite favorable in terms of the potential for economic benefits at a bargain price, maintaining the friendship of Russia, and blocking British expansion.

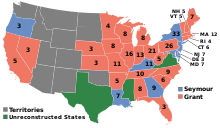

[142] Aside from Johnson, other contenders for the Democratic nomination included former Ohio representative George H. Pendleton, who was relatively unconcerned about Reconstruction and focused his appeal on the continued use of greenbacks, former New York governor Horatio Seymour, who had support among the party's conservative establishment but was reluctant to enter the race, and Chief Justice Salmon Chase.

[142] For vice president, the Democrats nominated Francis Preston Blair Jr., who campaigned on a promise to use the army to destroy the Southern governments that, he said, were led by "a semi-barborous race of blacks" who sought to "subject the white women to their unbridled lust.

"[144] The Democratic party platform embraced Johnson's presidency, thanking him for his "patriotic efforts" in "resisting the aggressions of Congress upon the Constitutional rights of the States and the people."

In his annual message to Congress in December, Johnson urged the repeal of the Tenure of Office Act and told legislators that, had they admitted their Southern colleagues in 1865, all would have been well.

He also issued, in his final months in office, pardons for crimes, including one for Dr. Samuel Mudd, controversially convicted of involvement in the Lincoln assassination (he had set Booth's broken leg) and imprisoned in Fort Jefferson on Florida's Dry Tortugas.

Memoirs from Northerners who had dealt with him, such as former vice president Henry Wilson and Maine Senator James G. Blaine, depicted him as an obstinate boor whose Reconstruction policies favored the South.

Leading the wave was Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James Ford Rhodes,[152] who ascribed Johnson's faults to his personal weaknesses, and blamed him for the problems of the postbellum South.

[153] Other early 20th-century historians, such as John Burgess, Woodrow Wilson, and William Dunning, all Southerners, concurred with Rhodes, believing Johnson flawed and politically inept, but concluding that he had tried to carry out Lincoln's plans for the South in good faith.

In James Schouler's 1913 History of the Reconstruction Period, the author accused Rhodes of being "quite unfair to Johnson", though agreeing that the former president had created many of his own problems through inept political moves.

[155] According to historian Glenn W. Lafantasie, who believes Buchanan the worst president, "Johnson is a particular favorite for the bottom of the pile because of his impeachment ... his complete mishandling of Reconstruction policy ... his bristling personality, and his enormous sense of self-importance.

[166] A 2006 poll of historians ranked Johnson's decision to oppose greater equality for African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War as the second-worst mistake ever made by a sitting president.

Because of his gross incompetence in federal office and his incredible miscalculation of the extent of public support for his policies, Johnson is judged as a great failure in making a satisfying and just peace.