Presidential transition of Franklin D. Roosevelt

At the time that Roosevelt's occurred, the term "presidential transition" had yet to be widely applied to the period between an individual's election as president of the United States and their assumption of the office.

[5] Additionally, friends and associates such as Edward J. Flynn, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., Jesse I. Straus, Frank C. Walker, and William H. Woodin advised Roosevelt during the transition.

[9] While there was much room for the passage of the farm policy Roosevelt was seeking in Congress (including among Republicans), Hoover made it clear he would not be willing to sign such legislation.

[8] After this, Hoover made their telegrams discussing this public, and released a White House statement suggesting that Roosevelt found it "undesirable" to engage in joint efforts relating to the economy.

Roosevelt responded to this White House statement, by saying "it is a pity" that Hoover was making the suggestion he was opposed to "cooperative action".

In January 1933, Roosevelt and Norris traveled together on a train from Washington, D.C. to the Tennessee Valley to assess the proposed projects that had been the subject of the vetoed bill.

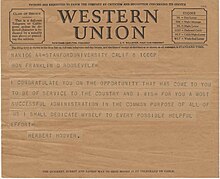

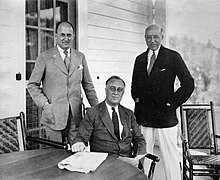

[16][17] On November 22, president-elect Roosevelt and outgoing president Hoover held their first post-election in-person meeting in the White House's Red Room.

[8] Hoover began the meeting by delivering to Roosevelt an hour long lecture on international economic matters.

[8] Wanting to avoid looking uncooperative, in early January, Roosevelt made a telephone call to Hoover and arranged for a second meeting.

[8] Instead of hosting the Roosevelts for a then-traditional pre-inauguration dinner, the Hoovers invited them for an afternoon tea the day prior to the inauguration.

[19] When Roosevelt arrived at the White House, he found that Hoover wanted to pull him into another meeting, this time with the Secretary of the Treasury and Chair of the Federal Reserve.

[21] Vice president-elect John Nance Garner was still speaker of the House for the lame duck session, and could have been a useful ally in passing legislation through Congress.

[26] Walsh died unexpectedly in early March, and Homer Stille Cummings was quickly selected to be Roosevelt's Attorney General.

[29] In Roosevelt's circle, Jesse I. Straus, president of the department store chain Macy's, was a favorite for the position of Secretary of Commerce.

[31] Laurin L. Henry speculated the Roosevelt had made a decision early into his transition to appoint a progressive Republican to the position of Secretary of the Interior.

[35] Raymond Moley would later recount that Roosevelt had strongly considered Robert Worth Bingham, Cordell Hull, and Owen D. Young for Secretary of State.

[37] On January 19, on his visit to Washington, D.C. for his second meeting with Hoover, Roosevelt offered Carter Glass the position of Secretary of the Treasury.

That evening, he offered the position to William H. Woodin, who McHenry Howe and Raymond Moley had recommended to Roosevelt.

Among those shot was Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who was sitting next to Roosevelt in his car and died from his injuries on March 6.

[8][39][40][41] On the day of the inauguration, Roosevelt and Hoover shared a tense car ride from the White House to the United States Capitol.

[11][43] In 2017, Amy Davidson Sorkin of The New Yorker suggested that Hoover believed the electorate had made a mistake, one that it was his duty to protect them from in his remaining months.

[8] Historian Eric Rauchway observed that Hoover conceded the election in form but not in political substance, and pursued a course of deliberate obstruction that was unequaled by any outgoing president as of November 2020.

In effect, Hoover wanted Roosevelt to renounce portions of the New Deal, like his public works programs, before taking office.