Priest-King (sculpture)

It is widely admired, as "the sculptor combined naturalistic detail with stylized forms to create a powerful image that appears much bigger than it actually is,"[3] and excepting possibly the Pashupati Seal, "nothing has come to symbolize the Indus Civilization better.

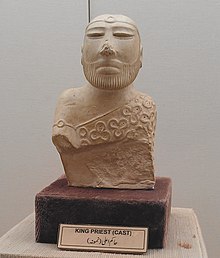

"[4] The sculpture shows a neatly bearded man with a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or headdress; his hair is combed back.

[10] The Urdu language title used by the museum (with the English "King-Priest") is not an exact translation, but حاکم اعلی (hakim aala), a well-known expression in Urdu-Persian-Arabic meaning a sovereign or bishop (who is entitled to sit in a chair of state on ceremonial occasions).

It has been compared to other IVC male figures, more fully complete, which show a seated position, with in some cases one raised knee and the other leg tucked beneath the body.

The back of the top of the head is flat, probably so that something now missing could be attached, and there are various theories as whether it was a carved "bun" or a more elaborate headdress, perhaps in other materials and only worn at times.

[14] The figure wears a toga-like outer garment that only covers one shoulder, with a pattern of trefoils; Pakistani sources like to suggest this is in the local ajrak technique of block-printing.

[9] Possible support for interpreting the figure as a religious person are the apparent representation of the eyes as fixed on the tip of his nose, a practice in yoga, and the similarity of the robe worn over one shoulder to later garments, including the Buddhist saṃghāti.

[18] The sculpture was found at a depth of 1.37 metres by the archaeologist Kashinath Narayan Dikshit (later head of the ASI) in the "D-K B" area of the city, and given the find number DK-1909.

The new Pakistani heritage authorities requested the return of the IVC artefacts, as almost all of those found by the time of independence had come from sites, like Mohenjo-daro, that were now in Pakistan.

[25] The others include two small full-length nude bronze female figures, both called "dancer"s by some, but alternative activities have been suggested, such as carrying offerings.

[29] There are also very numerous small and simple terracotta figures from all over the IVC, most female, generally similar to those produced over much of India later, indeed up to the present day.

Given the lack of evidence for a military-based monarch or ruling class, the model of some sort of theocracy was widely adopted by the early archaeologists.

[36] The British archaeologist Stuart Piggott, who was in India in the 1940s, thought the IVC was "a state ruled by priest-kings, wielding autocratic and absolute power from two main seats of government".

[37] Wheeler agreed, and asserted:[38] It can no longer be doubted that, whatever the source of their authority—and a dominant religious element can fairly be assumed—the lords of Harappa administered their city in a fashion not remote from that of the Priest-Kings or governors of Sumer and Akkad.Wheeler saw the damage inflicted on the large male figures as deliberate, done during the violent overthrow of the IVC by Aryan invaders that he postulated, an explanation for the end of the IVC that is now generally discredited.

[40] Priest-King figures had also been postulated for the Minoan civilization, which was roughly contemporary with the IVC, rising and falling a few centuries later, but whose discovery and excavation had been a couple of decades earlier.

In contrast to the IVC, a number of large and lavishly decorated "palaces" were extremely evident, but there was an absence of indications as to who, if anyone, had lived in them.

The head of the excavations, Sir Arthur Evans, had favoured the idea of a Priest-King, and had so titled a fragmentary relief fresco found at Knossos in 1901.