Priestley Riots

Both local and national issues stirred the passions of the rioters, from disagreements over public library book purchases, to controversies over Dissenters' attempts to gain full civil rights and their support of the French Revolution.

[2][1] While the riots were not initiated by Prime Minister William Pitt's administration, the national government was slow to respond to the Dissenters' pleas for help.

[7] In his Narrative of the Riots in Birmingham (1816), stationer and Birmingham historian William Hutton agreed, arguing that five events stoked the fires of religious friction: disagreements over inclusion of Priestley's books in the local public library; concerns over Dissenters' attempts to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts; religious controversy (particularly involving Priestley); an "inflammatory hand-bill"; and a dinner celebrating the outbreak of the French Revolution.

After 1787, the emergence of Dissenting groups formed for the sole purpose of overturning these laws began to divide the community; however, the repeal efforts failed in 1787, 1789 and 1790.

[12] In addition to these religious and political differences, both the lower-class rioters and their upper-class Anglican leaders had economic complaints against the middle-class Dissenters.

In these heady early days, supporters of the Revolution also believed that Britain's own system would be reformed as well: voting rights would be broadened and redistribution of Parliamentary constituency boundaries would eliminate so-called "rotten boroughs".

[16] While Burke supported aristocracy, monarchy, and the Established Church, liberals such as Charles James Fox supported the Revolution, and a programme of individual liberties, civic virtue and religious toleration, while radicals such as Priestley, William Godwin, Thomas Paine, and Mary Wollstonecraft, argued for a further programme of republicanism, agrarian socialism, and abolition of the "landed interest".

[19] On 11 July 1791, a Birmingham newspaper announced that on 14 July, the second anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, there would be a dinner at the local Royal Hotel to commemorate the outbreak of the French Revolution; the invitation encouraged "any Friend to Freedom" to attend: A number of gentlemen intend dining together on the 14th instant, to commemorate the auspicious day which witnessed the emancipation of twenty-six millions of people from the yoke of despotism, and restored the blessings of equal government to a truly great and enlightened nation; with whom it is our interest, as a commercial people, and our duty, as friends to the general rights of mankind, to promote a free intercourse, as subservient to a permanent friendship.

Any Friend to Freedom, disposed to join the intended temperate festivity, is desired to leave his name at the bar of the Hotel, where tickets may be had at Five Shillings each, including a bottle of wine; but no person will be admitted without one.

[24] About 90 hardy sympathisers of the French Revolution came to celebrate on 14 July; the banquet was led by James Keir, an Anglican industrialist who was a member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

The rioters, who "were recruited predominantly from the industrial artisans and labourers of Birmingham",[26] threw stones at the departing guests and sacked the hotel.

[32] Hutton later wrote a narrative of the events: I was avoided as a pestilence; the waves of sorrow rolled over me, and beat me down with multiplied force; every one came heavier than the last.

My wife, through long affliction, ready to quit my own arms for those of death; and I myself reduced to the sad necessity of humbly begging a draught of water at a cottage!...In the morning of the 15th I was a rich man; in the evening I was ruined.

[34]When the rioters arrived at John Taylor's other house at Moseley, Moseley Hall, they carefully moved all of the furniture and belongings of its current occupant, the frail Dowager Lady Carhampton, a relative of George III, out of the house before they burned it: they were specifically targeting those who disagreed with the king's policies and who, in not conforming to the Church of England, resisted state control.

[35] The homes of George Russell, a Justice of the Peace, Samuel Blyth, one of the ministers of New Meeting, Thomas Lee, and a Mr. Westley all came under attack on the 15th and 16th.

[37] When the military finally arrived to restore order on 17 and 18 July, most of the rioters had disbanded, although there were rumours that mobs were destroying property in Alcester and Bromsgrove.

[39] Having begun by attacking those who attended the Bastille celebration, the "Church-and-King" mob had finished up by extending their targets to include Dissenters of all kinds as well as members of the Lunar Society.

[43] If a concerted effort had been made by Birmingham's Anglican elite to attack the Dissenters, it was more than likely the work of Benjamin Spencer, a local minister, Joseph Carles, a Justice of the Peace and landowner, and John Brooke (1755-1802), an attorney, coroner, and under-sheriff.

[44] Although present at the riot's outbreak, Carles and Spencer made no attempt to stop the rioters, and Brooke seems to have led them to the New Meeting chapel.

[47] Only seventeen of the fifty rioters who had been charged were ever brought to trial; four were convicted, of whom one was pardoned, two were hanged, and the fourth was transported to Botany Bay.

[48] Although he had been forced to send troops to Birmingham to quell the disturbances, King George III commented, "I cannot but feel better pleased that Priestley is the sufferer for the doctrines he and his party have instilled, and that the people see them in their true light.

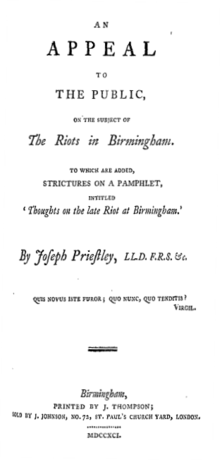

[3] Initially Priestley wanted to return and deliver a sermon on the Bible verse "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do," but he was dissuaded by friends convinced that it was too dangerous.

Though labouring under civil disabilities, as a Dissenter, I have long contributed my share to the support of government, and supposed I had the protection of its constitution and laws for my inheritance.

For then, as you have seen in my case, without any form of trial whatever, without any intimation of your crime, or of your danger, your houses and all your property may be destroyed, and you may not have the good fortune to escape with life, as I have done....What are the old French Lettres de Cachet, or the horrors of the late demolished Bastile, compared to this?