Storming of the Bastille

During the reign of Louis XVI, France faced a major economic crisis, caused in part by the cost of intervening in the American Revolution and exacerbated by regressive taxes, as well as poor harvests in the late 1780s.

[3] Furthermore, Finance Minister Calonne, Louis XVI's replacement for Jacques Necker, thought that lavish spending would secure loans by presenting the monarchy as wealthy.

[7] The crowd, on the authority of the meeting at the Palais-Royal, broke open the Prisons of the Abbaye to release some grenadiers of the French Guards, who had been reportedly imprisoned for refusing to fire on the people.

[10] On 11 July 1789, Louis XVI, acting under the influence of the conservative nobles of his privy council, dismissed and banished his finance minister, Jacques Necker (who had been sympathetic to the Third Estate) and completely reconstituted the ministry.

Camille Desmoulins successfully rallied the crowd by "mounting a table, pistol in hand, exclaiming: 'Citizens, there is no time to lose; the dismissal of Necker is the knell of Saint Bartholomew for patriots!

'"[6] The Swiss and German battalions referred to were among the foreign mercenary troops who made up a significant portion of the pre-revolutionary Royal Army and were seen as being less likely to be sympathetic to the popular cause than ordinary French soldiers.

[14] The French regiments included in the concentration appear to have been selected either because of the proximity of their garrisons to Paris or because their colonels were supporters of the reactionary "court party" opposed to reform.

[5] During the public demonstrations that started on 12 July, the multitude displayed busts of Necker and of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans and marched from the Palais Royal through the theatre district before it continued westward along the boulevards.

[15] The Royal commander, Baron de Besenval, fearing the results of a blood bath amongst the poorly-armed crowds or defections among his own men, then withdrew the cavalry towards Sèvres.

[16] Meanwhile, unrest was growing among the people of Paris who expressed their hostility against state authorities by attacking customs posts blamed for causing increased food and wine prices.

[19] The regiment of Gardes Françaises (French Guards) formed the permanent garrison of Paris and, with many local ties, was favourably disposed towards the popular cause.

With Paris becoming the scene of a general riot, Charles Eugene, not trusting the regiment to obey his order, posted sixty dragoons to station themselves before its depot in the Chaussée d'Antin.

[21] The future "Citizen King", Louis-Philippe, duc d'Orléans, witnessed those events as a young officer and was of the opinion that the soldiers would have obeyed orders if put to the test.

[26] The high cost of maintaining a garrisoned medieval fortress, for what was seen as having a limited purpose, had led to a decision being made shortly before the disturbances began to replace it with an open public space.

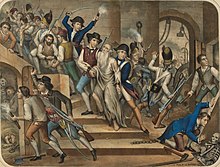

[36] The crowd gathered outside the fortress around mid-morning, calling for the pulling back of the seemingly threatening cannon from the embrasures of the towers and walls[37] and the release of the arms and gunpowder stored inside.

[26] Two representatives from the Hotel de Ville (municipal authorities from the Town Hall)[36] were invited into the fortress and negotiations began, while another was admitted around noon with definite demands.

[2] A small party climbed onto the roof of a building next to the gate to the inner courtyard of the fortress and broke the chains on the drawbridge, crushing one vainqueur as it fell.

The crowd seems to have felt that they had been intentionally drawn into a trap and the fighting became more violent and intense, while attempts by deputies to organise a cease-fire were ignored by the attackers.

A letter written by de Launay offering surrender but threatening to explode the powder stocks held if the garrison were not permitted to evacuate the fortress unharmed, was handed out to the besiegers through a gap in the inner gate.

[39] Ninety-eight attackers and one defender had died in the actual fighting or subsequently from wounds, a disparity accounted for by the protection provided to the garrison by the fortress walls.

[48] Their officer, Lieutenant Louis de Flue wrote a detailed report on the defense of the Bastille, which was incorporated in the logbook of the Salis-Samade Regiment and has survived.

Nonetheless, the fall of the Bastille marks the first time the regular citizens of Paris, the sans-culottes, made a major intervention into the Revolution's affairs.

The representatives remained however concerned that the Marshal de Broglie might still unleash a pro-Royalist coup to force them to adopt the order of 23 June,[56] and then dissolve the Assembly.

They settled at Turin, where Calonne, as agent for the count d'Artois and the prince de Condé, began plotting civil war within the kingdom and agitating for a European coalition against France.

[23] In rural areas, many went beyond this: some burned title-deeds and no small number of châteaux, as the "Great Fear" spread across the countryside during the weeks of 20 July to 5 August, with attacks on wealthy landlords impelled by the belief that the aristocracy was trying to put down the revolution.

[64][65] On 16 July 1789, two days after the Storming of the Bastille, John Frederick Sackville, British ambassador to France, reported to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds, "Thus, my Lord, the greatest revolution that we know anything of has been effected with, comparatively speaking—if the magnitude of the event is considered—the loss of very few lives.

[68] Although there were arguments that the Bastille should be preserved as a monument to liberation or as a depot for the new National Guard, the Permanent Committee of Municipal Electors at the Paris Town Hall gave the construction entrepreneur Pierre-François Palloy the commission of disassembling the building.

Various other pieces of the Bastille also survive, including stones used to build the Pont de la Concorde bridge over the Seine, and one of the towers, which was found buried in 1899 and is now at Square Henri-Galli in Paris, as well as the clock bells and pulley system, which are now in the Musée d’Art Campanaire.

[73] A Tale of Two Cities, the 1859 novel by Charles Dickens, dramatizes the Bastille storming in "Book The Second - the Golden Thread," Chapter 21, “Echoing Footsteps” (“Seven prisoners released, seven gory heads on pikes, the keys of the accursed fortress of the eight strong towers, some discovered letters and other memorials of prisoners of old time, long dead of broken hearts, - such, and such - like, the loudly echoing footsteps of Saint Antoine escort through the Paris streets in mid-July, one thousand seven hunderd and eighty-nine.”) La Révolution française, a 1989 French film dramatizes the storming in Part I.