Prime Minister of Italy

This power has been used to a quite variable extent in the history of the Italian state as it is strongly influenced by the political strength of individual ministers and thus by the parties they represent.

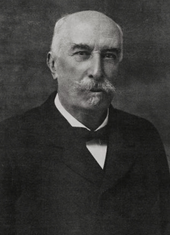

One of the most famous and influential prime ministers of this period was Francesco Crispi, a left-wing patriot and statesman, the first head of the government from Southern Italy.

Originally an enlightened Italian patriot and democrat liberal, Crispi went on to become a bellicose authoritarian prime minister, ally and admirer of Bismarck.

His career ended amid controversy and failure due to becoming involved in a major banking scandal and subsequently fell from power in 1896 after a devastating colonial defeat in Ethiopia.

[5] In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti, a leftist lawyer and politician, was appointed prime minister by King Umberto I, but after less than a year he was forced to resign and Crispi returned to power.

[7][8] A left-wing liberal[7] with strong ethical concerns,[9] Giolitti's periods in the office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.

Liberal proponents of free trade criticized the "Giolittian System", although Giolitti himself saw the development of the national economy as essential in the production of wealth.

[11] The Italian prime minister presided over a very unstable political system as in its first sixty years of existence (1861–1921) Italy changed its head of the government 37 times.

Regarding this situation, the first goal of Benito Mussolini, appointed in 1922, was to abolish the Parliament's ability to put him to a vote of no confidence, basing his power on the will of the King and the National Fascist Party alone.

After destroying all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes,[12] Mussolini and his Fascist followers consolidated their power through a series of laws that transformed the nation into a one-party dictatorship.

Mussolini remained in power until he was deposed by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1943 following a vote of no confidence by the Grand Council of Fascism and replaced by General Pietro Badoglio.

Bonomi was briefly succeeded by Ferruccio Parri in 1945 and then by Alcide de Gasperi, leader of the newly formed Christian Democracy (Democrazia Cristiana, DC) political party.

[13][14][15] The Years of Lead culminated in the assassination of the Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro in 1978 and the Bologna railway station massacre in 1980, where 85 people died.

In the early 1990s, Italy faced significant challenges as voters—disenchanted with political paralysis, massive public debt and the extensive corruption system (known as Tangentopoli) uncovered by the "Clean Hands" (mani pulite) investigation—demanded radical reforms.

In April 2013, after the general election in February, the Vice Secretary of the Democratic Party (PD) Enrico Letta led a government composed by both center-left and the center-right.

[21][22] In October 2022, President Mattarella appointed Giorgia Meloni as Italy's first female prime minister, following the resignation of Mario Draghi amidst a government crisis and a general election.