Wallachia

[24] Beginning with the tenth century, Byzantine, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and later Western sources mention the existence of small polities, possibly peopled by, among others, Vlachs led by knyazes and voivodes.

[26] One of the first written pieces of evidence of local voivodes is in connection with Litovoi (1272), who ruled over the land on each side of the Carpathians (including Hațeg Country in Transylvania), and refused to pay tribute to Ladislaus IV of Hungary.

In a charter by Radu I, the Wallachian voivode requests that tsar Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria order his customs officers at Rucăr and the Dâmboviţa River bridge to collect tax following the law.

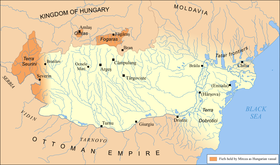

[31] As the entire Balkans became an integral part of the growing Ottoman Empire (a process that concluded with the fall of Constantinople to Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453), Wallachia became engaged in frequent confrontations in the final years of the reign of Mircea I (r. 1386–1418).

[33] He swung between alliances with Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, and Jagiellon Poland (taking part in the Battle of Nicopolis),[34] and accepted a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1417, after Mehmed I took control of Turnu Măgurele and Giurgiu.

[36] The peace signed in 1428 inaugurated a period of internal crisis, as Dan had to defend himself against Radu II, who led the first in a series of boyar coalitions against established princes.

[37] Victorious in 1431 (the year when the boyar-backed Alexander I Aldea took the throne), boyars were dealt successive blows by Vlad II Dracul (1436–1442; 1443–1447), who nevertheless attempted to compromise between the Ottoman Sultan and the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1462, Vlad III was defeated by Mehmed the Conqueror during his offensive at the Night Attack at Târgovişte before being forced to retreat to Târgoviște and accepting to pay an increased tribute.

[44] The late 15th century saw the ascension of the powerful Craiovești family, virtually independent rulers of the Oltenian banat, who sought Ottoman support in their rivalry with Mihnea cel Rău (1508–1510) and replaced him with Vlăduț.

His successor Mircea Ciobanul (1545–1554; 1558–1559), a prince without any claim to noble heritage, was imposed on the throne and consequently agreed to a decrease in autonomy (increasing taxes and carrying out an armed intervention in Transylvania – supporting the pro-Turkish John Zápolya).

[50] Initially profiting from Ottoman support, Michael the Brave ascended to the throne in 1593, and attacked the troops of Murad III north and south of the Danube in an alliance with Transylvania's Sigismund Báthory and Moldavia's Aron Vodă (see Battle of Călugăreni).

[citation needed] Following Michael's downfall, Wallachia was occupied by the Polish–Moldavian army of Simion Movilă (see Moldavian Magnate Wars), who held the region until 1602, and was subject to Nogai attacks in the same year.

[55] Furthermore, the growing importance of appointment to high office in front of land ownership brought about an influx of Greek and Levantine families, a process already resented by locals during the rules of Radu Mihnea in the early 17th century.

A close alliance between Gheorghe Ștefan and Matei's successor Constantin Șerban was maintained by Transylvania's George II Rákóczi, but their designs for independence from Ottoman rule were crushed by the troops of Mehmed IV in 1658–1659.

Wallachia became a target for Habsburg incursions during the last stages of the Great Turkish War around 1690, when the ruler Constantin Brâncoveanu secretly and unsuccessfully negotiated an anti-Ottoman coalition.

Brâncoveanu's reign (1688–1714), noted for its late Renaissance cultural achievements (see Brâncovenesc style), also coincided with the rise of Imperial Russia under Tsar Peter the Great—he was approached by the latter during the Russo-Turkish War of 1710–11, and lost his throne and life sometime after sultan Ahmed III caught news of the negotiations.

[60] Despite his denunciation of Brâncoveanu's policies, Ștefan Cantacuzino attached himself to Habsburg projects and opened the country to the armies of Prince Eugene of Savoy; he was himself deposed and executed in 1716.

Mavrocordatos himself was deposed by a boyar rebellion, and arrested by Habsburg troops during the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18, as the Ottomans had to concede Oltenia to Charles VI of Austria (the Treaty of Passarowitz).

[65] The region, organized as the Banat of Craiova and subject to an enlightened absolutist rule that soon disenchanted local boyars, was returned to Wallachia in 1739 (the Treaty of Belgrade, upon the close of the Austro-Russian–Turkish War (1735–39)).

[71] A period of crisis followed the Ottoman recovery: Oltenia was devastated by the expeditions of Osman Pazvantoğlu, a powerful rebellious pasha whose raids even caused Prince Constantine Hangerli to lose his life on suspicion of treason (1799), and Alexander Mourousis to renounce his throne (1801).

[74] During the period, Wallachia increased its strategic importance for most European states interested in supervising Russian expansion; consulates were opened in Bucharest, having an indirect but major impact on Wallachian economy through the protection they extended to Sudiți traders (who soon competed successfully against local guilds).

[75] The death of prince Alexander Soutzos in 1821, coinciding with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, established a boyar regency which attempted to block the arrival of Scarlat Callimachi to his throne in Bucharest.

[82] The 1829 Treaty of Adrianople placed Wallachia and Moldavia under Russian military rule, without overturning Ottoman suzerainty, awarding them the first common institutions and semblance of a constitution (see Regulamentul Organic).

[83] The treaty also allowed Moldavia and Wallachia to freely trade with countries other than the Ottoman Empire, which signalled substantial economic and urban growth, as well as improving the peasant situation.

[87] Opposition to Ghica's arbitrary and highly conservative rule, together with the rise of liberal and radical currents, was first felt with the protests voiced by Ion Câmpineanu (quickly repressed);[88] subsequently, it became increasingly conspiratorial, and centered on those secret societies created by young officers such as Nicolae Bălcescu and Mitică Filipescu.

Their pan-Wallachian coup d'état was initially successful only near Turnu Măgurele, where crowds cheered the Islaz Proclamation (9 June); among others, the document called for political freedoms, independence, land reform, and the creation of a national guard.

The emerging movement for a union of the Danubian Principalities (a demand first voiced in 1848, and a cause cemented by the return of revolutionary exiles) was advocated by the French and their Sardinian allies, supported by Russia and Prussia, but was rejected or suspicioned by all other overseers.

Internationally recognized only for the duration of his reign, the union was irreversible after the ascension of Carol I in 1866 (coinciding with the Austro-Prussian War, it came at a time when Austria, the main opponent of the decision, was not in a position to intervene).

[95] The very first document attesting the presence of Roma people in Wallachia dates back to 1385, and refers to the group as ațigani (from the Greek athinganoi, the origin of the Romanian term țigani, which is synonymous with "Gypsy").

[95] While it is possible that some Romani people were slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars, the bulk of them came from south of the Danube at the end of the 14th century, some time after the foundation of Wallachia.