Problem of Apollonius

Viète's approach, which uses simpler limiting cases to solve more complicated ones, is considered a plausible reconstruction of Apollonius' method.

The method of van Roomen was simplified by Isaac Newton, who showed that Apollonius' problem is equivalent to finding a position from the differences of its distances to three known points.

These developments provide a geometrical setting for algebraic methods (using Lie sphere geometry) and a classification of solutions according to 33 essentially different configurations of the given circles.

[3] The original approach of Apollonius of Perga has been lost, but reconstructions have been offered by François Viète and others, based on the clues in the description by Pappus of Alexandria.

A prized property in classical Euclidean geometry is the ability to solve problems using only a compass and a straightedge.

However, many such "impossible" problems can be solved by intersecting curves such as hyperbolas, ellipses and parabolas (conic sections).

[20] Prior to Viète's solution, Regiomontanus doubted whether Apollonius' problem could be solved by straightedge and compass.

[9] Practical algebraic methods were developed in the late 18th and 19th centuries by several mathematicians, including Leonhard Euler,[27] Nicolas Fuss,[9] Carl Friedrich Gauss,[28] Lazare Carnot,[29] and Augustin Louis Cauchy.

Isaac Newton (1687) refined van Roomen's solution, so that the solution-circle centers were located at the intersections of a line with a circle.

For any hyperbola, the ratio of distances from a point Z to a focus A and to the directrix is a fixed constant called the eccentricity.

The two directrices intersect at a point T, and from their two known distance ratios, Newton constructs a line passing through T on which Z must lie.

As described below, Apollonius' problem has ten special cases, depending on the nature of the three given objects, which may be a circle (C), line (L) or point (P).

Following Euclid a second time, Viète solved the LLL case (three lines) using the angle bisectors.

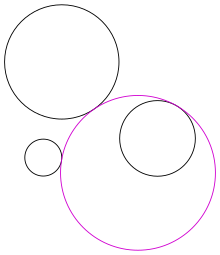

Viète used this approach to shrink one of the given circles to a point, thus reducing the problem to a simpler, already solved case.

This gives another way to calculate the maximum number of solutions and extend the theorem to higher-dimensional spaces.

In the first family (Figure 7), the solutions do not enclose the inner concentric circle, but rather revolve like ball bearings in the annulus.

Therefore, by the law of cosines, Here, a new constant C has been defined for brevity, with the subscript indicating whether the solution is externally or internally tangent.

The techniques of modern algebraic geometry, and in particular intersection theory, can be used to solve Apollonius's problem.

To see this, consider the incidence correspondence For a curve that is the vanishing locus of a single equation f = 0, the condition that the curve meets D at r with multiplicity m means that the Taylor series expansion of f|D vanishes to order m at r; it is therefore m linear conditions on the coefficients of f. This shows that, for each r, the fiber of Φ over r is a P1 cut out by two linear equations in the space of circles.

To prove that the intersection is generically finite, consider the incidence correspondence There is a morphism which projects Ψ onto its final factor of P3.

The two simplest cases are the problems of drawing a circle through three given points (PPP) or tangent to three lines (LLL), which were solved first by Euclid in his Elements.

The center of the solution circle is equally distant from all three points, and therefore must lie on the perpendicular bisector line of any two.

An exhaustive enumeration of the number of solutions for all possible configurations of three given circles, points or lines was first undertaken by Muirhead in 1896,[42] although earlier work had been done by Stoll[43] and Study.

[34][43] Alternative solutions based on the geometry of circles and spheres have been developed and used in higher dimensions.

[51] Soddy published his findings in the scientific journal Nature as a poem, The Kiss Precise, of which the first two stanzas are reproduced below.

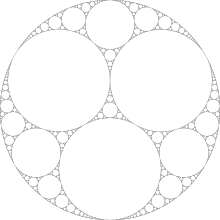

[55] This gasket is a fractal, being self-similar and having a dimension d that is not known exactly but is roughly 1.3,[56] which is higher than that of a regular (or rectifiable) curve (d = 1) but less than that of a plane (d = 2).

[57] The Apollonian gasket also has deep connections to other fields of mathematics; for example, it is the limit set of Kleinian groups.

[63] The principal application of Apollonius' problem, as formulated by Isaac Newton, is hyperbolic trilateration, which seeks to determine a position from the differences in distances to at least three points.

[7] Similarly, the location of an aircraft may be determined from the difference in arrival times of its transponder signal at four receiving stations.

[31] It is also used to determine the position of calling animals (such as birds and whales), although Apollonius' problem does not pertain if the speed of sound varies with direction (i.e., the transmission medium not isotropic).