Project HARP

Unlike conventional space launching methods that rely on rockets, HARP instead used very large guns to fire projectiles into the atmosphere at extremely high speeds.

By late 1960, CARDE and the Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) conducted several feasibility studies surrounding small gun-launched probes' structural integrity.

[7] Around the same time, BRL developed a smooth-bore, 5-inch gun system at Aberdeen Proving Ground that successfully launched a probe to altitudes exceeding 220,000 feet.

Working together with Donald Mordell, the university's Dean of Engineering, Bull moved forward with his space gun project and requested funding from various sources.

He was given a verbal promise for a $500,000 grant from the Canadian Department of Defence Production (CDDP), which was later reportedly denied due to bureaucratic opposition.

The U.S. Army provided Bull with substantial financial backing and two 16-inch naval gun barrels complete with a land mount and surplus powder charges, a heavy-duty crane, and a $750,000 radar tracking system.

[3][4][8] Bull and Mordell officially announced the HARP project as a program under McGill University's Space Research Institute at a press conference in March 1962.

In 1962, Bull and Mordell established a McGill University research station on Barbados (then still a British colony and part of the West Indies Federation) as HARP's main base of operations for its 16-inch super gun.

[1][3] As a result of McGill University's close connections with the island's Democratic Labour Party, Bull met with the Barbados Prime Minister Errol Barrow to arrange the construction of a firing site at Foul Bay, St.

[13][14] HARP reportedly received enthusiastic support from the Barbados government due to expectations that the island nation would become heavily involved in space exploration research.

[3][12][15] Hundreds of people from Barbados were employed to transport the two 140-ton gun tubes from the coast to the designated emplacement 21⁄2 miles from the beach using a temporary purpose-built railway.

[3] The projectiles fired by the 16-inch HARP gun on Barbados belonged to a family of cylindrical, finned missiles called Martlets, named after the martin bird that appeared on the McGill University crest.

The Martlets also carried payloads of metallic chaff, chemical smoke, or meteorological balloons to gather atmospheric data as well as telemetry antennas for tracking the missile's flight.

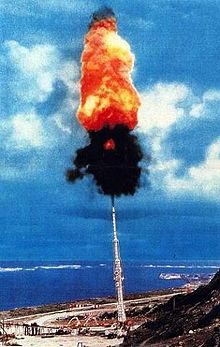

The firing of these Martlet missiles was always accompanied by a huge explosion that shook the houses within close proximity, leading to cracks in several areas.

[13][16] From late January to early February 1963, the 16-inch gun on Barbados conducted its first test series using the Martlet 1, the first of which flew for 145 seconds and reached an altitude of 26 km.

By March 1964, Canada's Department of Defence Production (DDP) agreed to provide joint funding for the HARP program for a total of $3 million per year.

[4][16] At this point, the project starting planning the launch of the Martlet 4, a projectile that used rocket jets that would ignite mid-flight to send the missile into orbit.

[3][20] On November 18, 1966, the HARP gun operated by BRL at Yuma Proving Ground launched an 84-kg Martlet 2 missile at 2,100 m/s, sending it briefly into space and setting a world altitude record of 179 km.

[4][16][23] Throughout 1966, the HARP program experienced a series of funding delays caused by immense opposition from critics in the Canadian government and growing bureaucratic pressures.

[24] On the American side, growing political and financial pressure caused by the Vietnam War and NASA's focus on large-scale traditional rockets strained funding for the project as well, exacerbating the program's problems even further.

[25] In addition to the High Altitude Research Laboratory at Barbados, a 16-inch HARP gun was constructed at the Highwater Range in Quebec and at Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona.

Smooth-bore 5-inch and 7-inch guns were set up at several different test sites, including Fort Greely, Alaska, Wallops Island, Virginia, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, and White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico.

They were designed to carry a 0.9 kg payload to an altitude of 65 km, which consisted of radar reflective chaff to collect wind data and small radiosondes that returned radio telemetry of information like temperature and humidity as they drifted back down under large parachutes.

[14] In 1962, a 10-ft extension was implemented for the 5-inch HARP gun by welding a second barrel section to the first, allowing it to launch projectiles at muzzle velocities of 1554 m/s (5,100 ft/sec) to altitudes of 73,100 m (240,000 ft).

During testing, a camera station set up on the islands of Barbados, Saint Vincent, and Grenada were used to photograph the trimethylaluminium trails released from the projectile during launch, which provided data on upper atmosphere wind velocities for different altitudes.

This limitation on size was extremely inconvenient when considering the future proposed payloads of Martlet rockets, including satellites and space probes.

They were built and tested for the HARP project but were ultimately not successful due to restrictions in funding and a severe lack of technical information regarding large rocket grains' behaviour under high acceleration loading.

Its basic concept revolved around packaging the rocket grain in a case with elastic properties to transmit the lateral strain to the gun tube.

A guidance and control system were developed for the orbital mission by Aviation Electric Limited of Montreal under the direction of McGill-BRL-Harry Diamond Laboratory group.

Information for on-board sensors was to be processed by the logic module, which provided commands to a cold gas thruster system which in turn adjusted the vehicle's orientation.