Projectile motion

In the particular case of projectile motion on Earth, most calculations assume the effects of air resistance are passive.

Galileo Galilei showed that the trajectory of a given projectile is parabolic, but the path may also be straight in the special case when the object is thrown directly upward or downward.

Taking other forces into account, such as aerodynamic drag or internal propulsion (such as in a rocket), requires additional analysis.

Ballistics (from Ancient Greek βάλλειν bállein 'to throw') is the science of dynamics that deals with the flight, behavior and effects of projectiles, especially bullets, unguided bombs, rockets, or the like; the science or art of designing and accelerating projectiles so as to achieve a desired performance.

The elementary equations of ballistics neglect nearly every factor except for initial velocity, the launch angle and a gravitational acceleration assumed constant.

Practical solutions of a ballistics problem often require considerations of air resistance, cross winds, target motion, acceleration due to gravity varying with height, and in such problems as launching a rocket from one point on the Earth to another, the horizon's distance vs curvature R of the Earth (its local speed of rotation

However, if an object was thrown and the Earth was suddenly replaced with a black hole of equal mass, it would become obvious that the ballistic trajectory is part of an elliptic orbit around that "black hole", and not a parabola that extends to infinity.

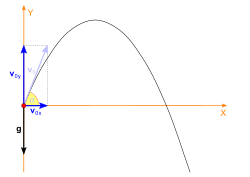

can be found if the initial launch angle θ is known: The horizontal component of the velocity of the object remains unchanged throughout the motion.

The vertical component of the velocity changes linearly,[note 2] because the acceleration due to gravity is constant.

If the projectile's position (x,y) and launch angle (θ or α) are known, the initial velocity can be found solving for v0 in the afore-mentioned parabolic equation: The parabolic trajectory of a projectile can also be expressed in polar coordinates instead of Cartesian coordinates.

Because of this, we can find the time to reach a target using the displacement formula for the horizontal velocity:

This equation will give the total time t the projectile must travel for to reach the target's horizontal displacement, neglecting air resistance.

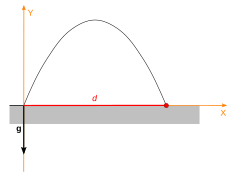

This distance is: According to the work-energy theorem the vertical component of velocity is: These formulae ignore aerodynamic drag and also assume that the landing area is at uniform height 0.

, To hit a target at range x and altitude y when fired from (0,0) and with initial speed v, the required angle(s) of launch θ are: The two roots of the equation correspond to the two possible launch angles, so long as they aren't imaginary, in which case the initial speed is not great enough to reach the point (x,y) selected.

The length of the parabolic arc traced by a projectile, L, given that the height of launch and landing is the same (there is no air resistance), is given by the formula: where

The expression can be obtained by evaluating the arc length integral for the height-distance parabola between the bounds initial and final displacement (i.e. between 0 and the horizontal range of the projectile) such that: If the time-of-flight is t, Air resistance creates a force that (for symmetric projectiles) is always directed against the direction of motion in the surrounding medium and has a magnitude that depends on the absolute speed:

[8] The transition between these behaviours is determined by the Reynolds number, which depends on object speed and size, density

around 0.15 cm2/s, this means that the drag force becomes quadratic in v when the product of object speed and diameter is more than about 0.015 m2/s, which is typically the case for projectiles.

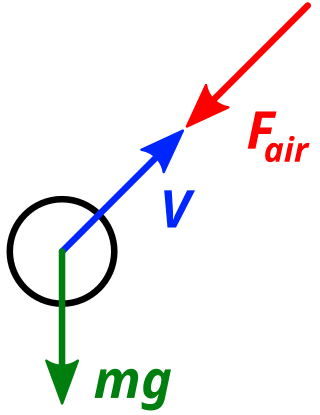

The free body diagram on the right is for a projectile that experiences air resistance and the effects of gravity.

causes a very simple differential equation of motion in which the 2 cartesian components become completely independent, and it is thus easier to solve.

(2) Solving (1) is an elementary differential equation, thus the steps leading to a unique solution for vx and, subsequently, x will not be enumerated.

(2a) This first order, linear, non-homogeneous differential equation may be solved a number of ways; however, in this instance, it will be quicker to approach the solution via an integrating factor

With a bit of algebra to simplify (3a): The total time of the journey in the presence of air resistance (more specifically, when

While in the case of zero air resistance this equation can be solved elementarily, here we shall need the Lambert W function.

Some algebra shows that the total time of flight, in closed form, is given as[10] The most typical case of air resistance, in case of Reynolds numbers above about 1000, is Newton drag with a drag force proportional to the speed squared,

In air, which has a kinematic viscosity around 0.15 cm2/s, this means that the product of object speed and diameter must be more than about 0.015 m2/s.

[1/m]) A projectile motion with drag can be computed generically by numerical integration of the ordinary differential equation, for instance by applying a reduction to a first-order system.

The equation to be solved is This approach also allows to add the effects of speed-dependent drag coefficient, altitude-dependent air density (in product

This may be done for various reasons such as increasing distance to the horizon to give greater viewing/communication range or for changing the angle with which a missile will impact on landing.

The trajectory then generalizes (without air resistance) from a parabola to a Kepler-ellipse with one focus at the center of the Earth (shown in fig.

without drag (a parabole)

with Stokes' drag

with Newtonian drag