Homography

Historically, homographies (and projective spaces) have been introduced to study perspective and projections in Euclidean geometry, and the term homography, which, etymologically, roughly means "similar drawing", dates from this time.

A projective space may be constructed as the set of the lines of a vector space over a given field (the above definition is based on this version); this construction facilitates the definition of projective coordinates and allows using the tools of linear algebra for the study of homographies.

For sake of simplicity, unless otherwise stated, the projective spaces considered in this article are supposed to be defined over a (commutative) field.

A large part of the results remain true, or may be generalized to projective geometries for which these theorems do not hold.

Historically, the concept of homography had been introduced to understand, explain and study visual perspective, and, specifically, the difference in appearance of two plane objects viewed from different points of view.

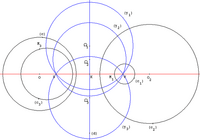

With these definitions, a perspectivity is only a partial function, but it becomes a bijection if extended to projective spaces.

This matrix is defined up to the multiplication by a nonzero element of K. The homogeneous coordinates [x0 : ... : xn] of a point and the coordinates [y0 : ... : yn] of its image by φ are related by When the projective spaces are defined by adding points at infinity to affine spaces (projective completion) the preceding formulas become, in affine coordinates, which generalizes the expression of the homographic function of the next section.

With this representation of the projective line, the homographies are the mappings which are called homographic functions or linear fractional transformations.

In the case of the complex projective line, which can be identified with the Riemann sphere, the homographies are called Möbius transformations.

These correspond precisely with those bijections of the Riemann sphere that preserve orientation and are conformal.

[3] In the study of collineations, the case of projective lines is special due to the small dimension.

This means that the fundamental theorem of projective geometry (see below) remains valid in the one-dimensional setting.

A homography of a projective line may also be properly defined by insisting that the mapping preserves cross-ratios.

This result is much more difficult in synthetic geometry (where projective spaces are defined through axioms).

It is not difficult to verify that changing the ei and v, without changing the frame nor p(v), results in multiplying the projective coordinates by the same nonzero element of K. The projective space Pn(K) = P(Kn+1) has a canonical frame consisting of the image by p of the canonical basis of Kn+1 (consisting of the elements having only one nonzero entry, which is equal to 1), and (1, 1, ..., 1).

In synthetic geometry, they are traditionally defined as the composition of one or several special homographies called central collineations.

The image B′ of a point B that does not belong to ℓ may be constructed in the following way: let S = AB ∩ M, then B′ = SA′ ∩ OB.

If projective spaces are defined by means of axioms (synthetic geometry), the third part is simply a definition.

On the other hand, if projective spaces are defined by means of linear algebra, the first part is an easy corollary of the definitions.

As all the projective spaces of the same dimension over the same field are isomorphic, the same is true for their homography groups.

For example, PGL(2, 7) acts on the eight points in the projective line over the finite field GF(7), while PGL(2, 4), which is isomorphic to the alternating group A5, is the homography group of the projective line with five points.

In other words, if d has homogeneous coordinates [k : 1] over the projective frame (a, b, c), then [a, b; c, d] = k.[13] Suppose A is a ring and U is its group of units.

The conformal group of spacetime can be represented with homographies where A is the composition algebra of biquaternions.

[15] In his review of a brute force approach to periodicity of homographies, H. S. M. Coxeter gave this analysis:

| 1. | The width of the side street, W is computed from the known widths of the adjacent shops. |

| 2. | As a vanishing point , V is visible, the width of only one shop is needed. |