Complex plane

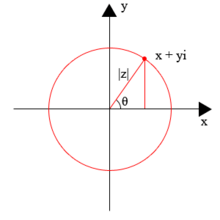

; then for a complex number z its absolute value |z| coincides with its Euclidean norm, and its argument arg(z) with the angle turning from 1 to z.

The theory of contour integration comprises a major part of complex analysis.

Here it is customary to speak of the domain of f(z) as lying in the z-plane, while referring to the range of f(z) as a set of points in the w-plane.

[3] Such plots are named after Jean-Robert Argand (1768–1822), although they were first described by Norwegian–Danish land surveyor and mathematician Caspar Wessel (1745–1818).

[note 3] Argand diagrams are frequently used to plot the positions of the zeros and poles of a function in the complex plane.

Given a point in the plane, draw a straight line connecting it with the north pole on the sphere.

Since the interior of the unit circle lies inside the sphere, that entire region (|z| < 1) will be mapped onto the southern hemisphere.

[5] Imagine for a moment what will happen to the lines of latitude and longitude when they are projected from the sphere onto the flat plane.

This is not the only possible yet plausible stereographic situation of the projection of a sphere onto a plane consisting of two or more values.

For instance, the north pole of the sphere might be placed on top of the origin z = −1 in a plane that is tangent to the circle.

On the real number line we could circumvent this problem by erecting a "barrier" at the single point x = 0.

A bigger barrier is needed in the complex plane, to prevent any closed contour from completely encircling the branch point z = 0.

By making a continuity argument we see that the (now single-valued) function w = z1/2 maps the first sheet into the upper half of the w-plane, where 0 ≤ arg(w) < π, while mapping the second sheet into the lower half of the w-plane (where π ≤ arg(w) < 2π).

We can "cut" the plane along the real axis, from −1 to 1, and obtain a sheet on which g(z) is a single-valued function.

where γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant, and has simple poles at 0, −1, −2, −3, ... because exactly one denominator in the infinite product vanishes when z = 0, or a negative integer.

[note 5] Since all its poles lie on the negative real axis, from z = 0 to the point at infinity, this function might be described as "holomorphic on the cut plane, the cut extending along the negative real axis, from 0 (inclusive) to the point at infinity."

Alternatively, Γ(z) might be described as "holomorphic in the cut plane with −π < arg(z) < π and excluding the point z = 0."

Cutting the complex plane ensures not only that Γ(z) is holomorphic in this restricted domain – but also that the contour integral of the gamma function over any closed curve lying in the cut plane is identically equal to zero.

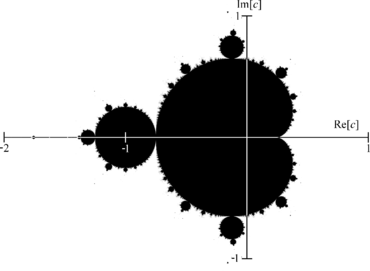

A fundamental consideration in the analysis of these infinitely long expressions is identifying the portion of the complex plane in which they converge to a finite value.

it makes sense to cut the plane along the entire imaginary axis and establish the convergence of this series where the real part of z is not zero before undertaking the more arduous task of examining f(z) when z is a pure imaginary number.

It is also possible to "glue" those two sheets back together to form a single Riemann surface on which f(z) = z1/2 can be defined as a holomorphic function whose image is the entire w-plane (except for the point w = 0).

[6] To understand why f is single-valued in this domain, imagine a circuit around the unit circle, starting with z = 1 on the first sheet.

Once again we begin with two copies of the z-plane, but this time each one is cut along the real line segment extending from z = −1 to z = 1 – these are the two branch points of g(z).

We flip one of these upside down, so the two imaginary axes point in opposite directions, and glue the corresponding edges of the two cut sheets together.

We can verify that g is a single-valued function on this surface by tracing a circuit around a circle of unit radius centered at z = 1.

The equation is normally expressed as a polynomial in the parameter s of the Laplace transform, hence the name s-plane.

Points in the s-plane take the form s = σ + jω, where 'j' is used instead of the usual 'i' to represent the imaginary component (the variable 'i' is often used to denote electrical current in engineering contexts).

This is a geometric principle which allows the stability of a closed-loop feedback system to be determined by inspecting a Nyquist plot of its open-loop magnitude and phase response as a function of frequency (or loop transfer function) in the complex plane.

For a point z = x + iy in the complex plane, the squaring function z2 and the norm-squared x2 + y2 are both quadratic forms.

These distinct faces of the complex plane as a quadratic space arise in the construction of algebras over a field with the Cayley–Dickson process.