Prostration

Typically prostration is distinguished from the lesser acts of bowing or kneeling by involving a part of the body above the knee, especially the hands, touching the ground.

[1] In various cultures and traditions, prostrations are similarly used to show respect to rulers, civil authorities and social elders or superiors, as in the Chinese kowtow or Ancient Greek proskynesis.

Many religious institutions (listed alphabetically below) use prostrations to embody the lowering, submitting or relinquishing of the individual ego before a greater spiritual power or presence.

[5] Tibetan pilgrims often progress by prostrating themselves fully at each step, then moving forward as they get up, in such a way that they have lain on their face on each part of their route.

[10] Among Old Ritualists, a prayer rug known as the Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.

[11] The Catholic, Lutheran, and Anglican Churches use full prostrations, lying flat on the floor face down, during the imposition of Holy Orders,[12] Religious Profession and the Consecration of Virgins.

In Eastern Orthodox (Byzantine Rite) worship, prostrations are preceded by making the sign of the cross and consist of kneeling and touching the head to the floor.

In Judaism, the Tanakh and Talmudic texts as well as writings of Gaonim and Rishonim indicate that prostration was very common among Jewish communities until some point during the Middle Ages.

In Mishneh Torah, Maimonides states full prostration (with one's body pressed flat to the earth) should be practiced at the end of the Amidah, recited thrice daily.

Judaism forbids prostration directly on a stone surface in order to prevent conflation with similar practices of Canaanite polytheists.

Other prostrations practiced by Sikhs from an Indian culture are touching of the feet to show respect and great humility (generally done to grandparents and other family elders).

Outside of traditional religious institutions, prostrations are used to show deference to worldly power, in the pursuit general spiritual advancement and as part of a physical-health regimen.

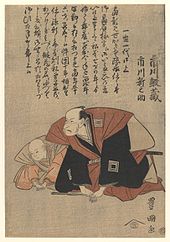

In Japan, a common form of prostration is called dogeza, which was used as a sign of deep respect and submission for the elders of a family, guests, samurai, daimyōs and the Emperor.

In traditional and contemporary Yoruba culture, younger male family and community members greet elders by assuming a position called "ìdọ̀bálẹ̀".

This traditional form is being replaced by a more informal bow and touching the fingertips to the floor in front of an elder with one hand, while bending slightly at the knee.