Sign language

Linguists consider both spoken and signed communication to be types of natural language, meaning that both emerged through an abstract, protracted aging process and evolved over time without meticulous planning.

[3] This is supported by the fact that there is substantial overlap between the neural substrates of sign and spoken language processing, despite the obvious differences in modality.

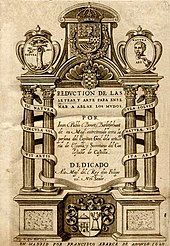

[10] Monastic sign languages were the basis for the first known manual alphabet used in deaf schools, developed by Pedro Ponce de León.

[13] It is considered the first modern treatise of sign language phonetics, setting out a method of oral education for deaf people and a manual alphabet.

[15] In 1648, John Bulwer described "Master Babington", a deaf man proficient in the use of a manual alphabet, "contryved on the joynts of his fingers", whose wife could converse with him easily, even in the dark through the use of tactile signing.

The earliest known printed pictures of consonants of the modern two-handed alphabet appeared in 1698 with Digiti Lingua (Latin for Language [or Tongue] of the Finger), a pamphlet by an anonymous author who was himself unable to speak.

[24] Descendants of this alphabet have been used by deaf communities, at least in education, in the former British colonies India, Australia, New Zealand, Uganda and South Africa, as well as the republics and provinces of the former Yugoslavia, Grand Cayman Island in the Caribbean, Indonesia, Norway, Germany and the United States.

During the Polygar Wars against the British, Veeran Sundaralingam communicated with Veerapandiya Kattabomman's mute younger brother, Oomaithurai, by using their own sign language.

[clarification needed] Frenchman Charles-Michel de l'Épée published his manual alphabet in the 18th century, which has survived largely unchanged in France and North America until the present time.

In 1755, Abbé de l'Épée founded the first school for deaf children in Paris; Laurent Clerc was arguably its most famous graduate.

As in spoken languages, these meaningless units are represented as (combinations of) features, although coarser descriptions are often also made in terms of five "parameters": handshape (or handform), orientation, location (or place of articulation), movement, and non-manual expression.

Now they are sometimes called phonemes when describing sign languages too, since the function is essentially the same, but more commonly discussed in terms of "features"[1] or "parameters".

[clarification needed] Common linguistic features of many sign languages are the occurrence of classifier constructions, a high degree of inflection by means of changes of movement, and a topic-comment syntax.

Hearing teachers in deaf schools, such as Charles-Michel de l'Épée or Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, are often incorrectly referred to as "inventors" of sign language.

It has only one sign language with two variants due to its history of having two major educational institutions for the deaf which have served different geographic areas of the country.

Postures or movements of the body, head, eyebrows, eyes, cheeks, and mouth are used in various combinations to show several categories of information, including lexical distinction, grammatical structure, adjectival or adverbial content, and discourse functions.

[55] Nancy Frishberg concluded that though originally present in many signs, iconicity is degraded over time through the application of natural grammatical processes.

[53] In 1978, psychologist Roger Brown was one of the first to suggest that the properties of ASL give it a clear advantage in terms of learning and memory.

In contrast to Brown, linguists Elissa Newport and Richard Meier found that iconicity "appears to have virtually no impact on the acquisition of American Sign Language".

[82] Linguistic typology (going back to Edward Sapir) is based on word structure and distinguishes morphological classes such as agglutinating/concatenating, inflectional, polysynthetic, incorporating, and isolating ones.

In this way, since subjects of intransitives are treated similarly to objects of transitives, incorporation in sign languages can be said to follow an ergative pattern.

They also found that there are differences in the grammatical morphology of ASL sentences between the two groups, all suggesting that there is a very important critical period in learning signed languages.

"[95] For example, in 2015 at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, João Paulo Ampessan wrote his linguistics master's dissertation in Brazilian Sign Language using Sutton SignWriting.

[100] Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites.

They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, and Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

Live sign interpretation of important televised events is increasingly common but still an informal industry [108] In traditional analogue broadcasting, some programmes are repeated outside main viewing hours with a signer present.

The three colors which make up the flag design are representative of Deafhood and humanity (dark blue), sign language (turquoise), and enlightenment and hope (yellow).

Still, this kind of system is inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and it comes nowhere near meeting the standards linguists use to describe a complete language.

[128] There have been several notable examples of scientists teaching signs to non-human primates in order to communicate with humans,[129] such as chimpanzees,[130][131][132][133][134][135][136] gorillas[137] and orangutans.

[139][140][141][142][143] Notable examples of animals who have learned signs include: One theory of the evolution of human language states that it developed first as a gestural system, which later shifted to speech.