Protein structure

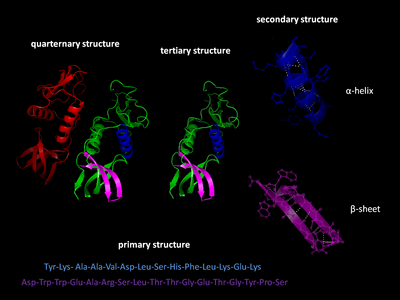

The primary structure of a protein refers to the sequence of amino acids in the polypeptide chain.

A specific sequence of nucleotides in DNA is transcribed into mRNA, which is read by the ribosome in a process called translation.

Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylations and glycosylations are usually also considered a part of the primary structure, and cannot be read from the gene.

Secondary structure refers to highly regular local sub-structures on the actual polypeptide backbone chain.

Two main types of secondary structure, the α-helix and the β-strand or β-sheets, were suggested in 1951 by Linus Pauling.

They have a regular geometry, being constrained to specific values of the dihedral angles ψ and φ on the Ramachandran plot.

Both the α-helix and the β-sheet represent a way of saturating all the hydrogen bond donors and acceptors in the peptide backbone.

They should not be confused with random coil, an unfolded polypeptide chain lacking any fixed three-dimensional structure.

The folding is driven by the non-specific hydrophobic interactions, the burial of hydrophobic residues from water, but the structure is stable only when the parts of a protein domain are locked into place by specific tertiary interactions, such as salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and the tight packing of side chains and disulfide bonds.

Bertolini et al. in 2021[8] presented evidence that homomer formation may be driven by interaction between nascent polypeptide chains as they are translated from mRNA by nearby adjacent ribosomes.

Transitions between these states typically occur on nanoscales, and have been linked to functionally relevant phenomena such as allosteric signaling[12] and enzyme catalysis.

[14] Examples include motor proteins, such as myosin, which is responsible for muscle contraction, kinesin, which moves cargo inside cells away from the nucleus along microtubules, and dynein, which moves cargo inside cells towards the nucleus and produces the axonemal beating of motile cilia and flagella.

Creating these files requires determining which of the various theoretically possible protein conformations actually exist.

One approach is to apply computational algorithms to the protein data in order to try to determine the most likely set of conformations for an ensemble file.

There are multiple methods for preparing data for the Protein Ensemble Database that fall into two general methodologies – pool and molecular dynamics (MD) approaches (diagrammed in the figure).

This pool is then subjected to more computational processing that creates a set of theoretical parameters for each conformation based on the structure.

Conformational subsets from this pool whose average theoretical parameters closely match known experimental data for this protein are selected.

The alternative molecular dynamics approach takes multiple random conformations at a time and subjects all of them to experimental data.

This approach often applies large amounts of experimental data to the conformations which is a very computationally demanding task.

[16] The conformational ensembles were generated for a number of highly dynamic and partially unfolded proteins, such as Sic1/Cdc4,[18] p15 PAF,[19] MKK7,[20] Beta-synuclein[21] and P27[22] As it is translated, polypeptides exit the ribosome mostly as a random coil and folds into its native state.

[23][24] The final structure of the protein chain is generally assumed to be determined by its amino acid sequence (Anfinsen's dogma).

[27] This method allows one to measure the three-dimensional (3-D) density distribution of electrons in the protein, in the crystallized state, and thereby infer the 3-D coordinates of all the atoms to be determined to a certain resolution.

Novel implementations of this approach, including fast parallel proteolysis (FASTpp), can probe the structured fraction and its stability without the need for purification.

Protein structure databases are critical for many efforts in computational biology such as structure based drug design, both in developing the computational methods used and in providing a large experimental dataset used by some methods to provide insights about the function of a protein.