Proto-Indo-European society

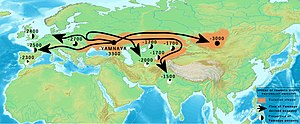

[3] Steppe economies underwent a revolutionary change between 4200 and 3300 BCE, in a shift from a partial reliance on herding, when domesticated animals were probably used principally as a ritual currency for public sacrifices, to a later regular dietary dependence on cattle, and either sheep or goat meat and dairy products.

[12] The Late Khvalynsk and Repin cultures (3900–3300), associated with the classic (post-Anatolian) Proto-Indo-European language, showed the first traces of cereal cultivation after 4000, in the context of a slow and partial diffusion of farming from the western parts of the steppes to the east.

[14] Yamnaya chiefdoms had institutionalized differences in prestige and power, and their society was organized along patron-client reciprocity, a mutual exchange of gifts and favors between their patrons, the gods, and human clients.

[36] The free part of society was composed of an elite class of priests, kings and warriors, along with the commoners,[36] with each tribe following a chief (*wiḱpots) sponsoring feasts and ceremonies, and immortalized in praise poetry.

His wife probably also played a complementary role: some evidence suggest that she would have kept her position as the mistress (*pot-n-ih₂) of the household in the event her husband dies, while the eldest son would have become the new master.

[43] The Proto-Indo-European expansionist kinship system was likely supported by both marital exogamy (the inclusion of foreign women through marriage) and the exchange of foster children with other families and clans, as suggested by genetic evidence and later attestations from Indo-European-speaking groups.

Public feasts sponsored by such patrons were a way for them to promote and secure a political hierarchy built on the unequal mobilization of labor and resources, by displaying their generosity towards the rest of the community.

[49] According to Anthony, the domestication of horses and the introduction of the wagon in the Pontic-Caspian steppe between 4500 and 3500 BCE led to an increase in mobility across the Yamnaya horizon, and eventually to the emergence of a guest-host political structure.

As various herding clans began to move across the steppes, especially during harsh seasons, it became necessary to regulate local migrations on the territories of tribes which had likely restricted these obligations to their kins or co-residents (*h₂erós) until then.

The obligation could even be heritable: Homer’s warriors, Glaukos and Diomedes, stopped fighting and presented gifts to each other when they learned that their grandfathers had shared a guest-host relationship.

[55][56] For instance, the word *serk- ('to make a circle, complete') designated a type of compensation where the father (or master) had to either pay for the damages caused by his son (or slave), or surrender the perpetrator to the offended party.

It is one of the most securely reconstructed Proto-Indo-European words, with cognates attested in most sub-families: Latin artus ('joint'); Middle High German art ('innate feature, nature, fashion'); Greek artús (ἀρτύς, 'arrangement'), possibly arete (ἀρετή, 'excellence');[60] Armenian ard (արդ, 'ornament, shape'); Avestan arəta- ('order') and ṛtá ('truth'); Sanskrit ṛtú- (ऋतु, 'right time, order, rule'); Hittite āra (𒀀𒀀𒊏, 'right, proper');[61] Tocharian A ārt- ('to praise, be pleased with').

[63][64] Dumézil initially contended that it derived from an actual division in Indo-European societies, but later toned down his approach by representing the system as fonctions or general organizing principles.

[77] Other deities, such as the weather-god *Perkʷunos and the guardian of roads and herds, *Péh₂usōn, are probably late innovations since they are attested in a restricted number of traditions, Western (European) and Graeco-Aryan, respectively.

[78] Since the earliest evidence for the burning of the plant was found in Romanian kurgans dated 3,500 BCE, some scholars suggest that cannabis was first used as a psychoactive drug by Proto-Indo-Europeans during ritual ceremonies, a custom they eventually spread throughout western Eurasia during their migrations.

[52][108] A number of scholars propose that Proto-Indo-European rituals included the requirement that young unmarried men initiate into manhood by joining a warrior-band named *kóryos.

[68] During their initiation period, the young males wore the skin and bore the names of wild animals, especially wolves (*wl̩kʷo) and dogs (*ḱwōn), in order to assume their nature and escape the rules and taboos of their host society.

In later Indo-European traditions, notably the (half-)naked warrior figures of Germanic and Celtic art, *kóryos raiders wore a belt that bound them to their leader and the gods, and little else.

[114][115] In a mostly patriarchal economy based on bride competition, the escalation of the bride-price in periods of climate change could have resulted in an increase in cattle raiding by unmarried men.

[117][22][110] The use of two-word compound words for personal names, typically but not always ascribing some noble or heroic feat to their bearer, is so common in Indo-European languages that it is certainly an inherited feature.

"good-fame", meaning "possessing good fame") derive the Liburnian Vescleves, the Greek Eukleḗs (Εὐκλεής), the Old Persian Huçavah, the Avestan Haosravah-, and the Sanskrit Suśráva.

[122] Proto-Indo-Europeans possessed a Neolithic mixed economy based on livestock and subsidiary agriculture, with a wide range of economic regimes and various degrees of mobility that could be expected across the large Pontic-Caspian steppe.

[123] Tribes were typically more influenced by farming in the western Dnieper-Donets region, where cereal cultivation was practised, while the eastern Don-Volga steppes were inhabited by semi-nomadic and pastoral populations mostly relying on herding.

Copper objects show an artistic influence from Old Europe, and the appearance of sacrificed animals suggest that a new set of rituals emerged following the introduction of herding from the west.

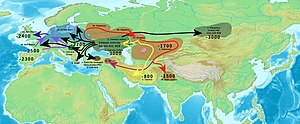

[125] Proto-Indo-European speakers also had indirect contacts with Uruk around 3700–3500 through the North Caucasian Maikop culture, a trade route that introduced the wheeled wagon into the Caspian-Pontic steppes.

Wheel-made pottery imported from Mesopotamia were found in the Northern Caucasus, and Maikop chieftain was buried wearing Mesopotamian symbols of power—the lion paired with the bull.

[129] Although wheels were most likely not invented by Proto-Indo-Europeans, the word *kʷekʷlóm is a native derivation of the root *kʷel- ("to turn") rather than a borrowing, suggesting short contacts with the people who introduced the concept to them.

[136][135] Proto-Indo-Europeans produced textile, as attested by the reconstructed roots for wool (*wĺh₂neh₂), flax (*linom), sewing (*syuh₁-), spinning (*(s)pen-), weaving (*h₂/₃webʰ-) and plaiting (*pleḱ-), as well as needle (*skʷēis) and thread (*pe/oth₂mo).

[127][74] The domestication of the horse (*h₁éḱwos), thought to be an extinct Tarpan species,[139] probably originated with these peoples, and scholars invoke this innovation as a factor contributing to their increased mobility and rapid expansion.

[146] Ritual and mythological concepts connected with wolves, in some cases similar with Native American beliefs, may represent a common Ancient North Eurasian heritage: mai-coh meant both "wolf" and "witch" among Navajos, and shunk manita tanka a "doglike powerful spirit" among Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, while the Proto-Indo-European root *ṷeid ("knowledge, clairvoyance") designated the wolf in both Hittite (ṷetna) and Old Norse (witnir), and a "werewolf" in Slavic languages (Serbian vjedogonja and vukodlak, Slovenian vedanec, Ukrainian viščun).