Proto-orthodox Christianity

[2] Ehrman argues that when this group became prominent by the end of the third century, it "stifled its opposition, it claimed that its views had always been the majority position and that its rivals were, and always had been, 'heretics', who willfully 'chose' to reject the 'true belief'.

"[4]: 7:57 Ehrman expands on the thesis of German New Testament scholar Walter Bauer (1877–1960), laid out in his primary work Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity (1934).

Bauer hypothesised that the Church Fathers, most notably Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History, "had not given an objective account of the relationship of early Christian groups."

[note 1] In modern times, many non-orthodox early Christian writings were discovered by scholars, gradually challenging the traditional Eusebian narrative.

But because the church in the city of Rome was "proto-orthodox", in Ehrman's terms, Bauer contended they had strategic advantages over all other sects because of their proximity to the Roman Empire's centre of power.

[5]: 15:48 According to Ehrman, proto-orthodox Christianity bequeathed to subsequent generations "four Gospels to tell us virtually everything we know about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus" and "handed down to us the entire New Testament, twenty-seven books".

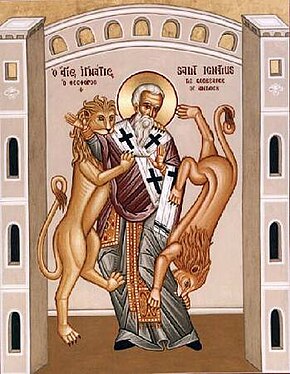

[7] Martyrdom played a major role in proto-orthodox Christianity, as exemplified by Ignatius of Antioch in the beginning of the second century.

[15] Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, in his Easter letter of 367,[16] listed the same twenty-seven New Testament books as found in the Canon of Trent.

[5]: 0:21 For Ehrman, in the canonical gospels, Jesus is characterized as a Jewish faith healer who ministered to the most despised people of the local culture.