Protoceratops

In 1900 Henry Fairfield Osborn suggested that Central Asia may have been the center of origin of most animal species, including humans, which caught the attention of explorer and zoologist Roy Chapman Andrews.

This idea later gave rise to the First (1916 to 1917), Second (1919) and Third (1921 to 1930) Central Asiatic Expeditions to China and Mongolia, organized by the American Museum of Natural History under the direction of Osborn and field leadership of Andrews.

Back in Beijing, the skull Shackelford had found was sent to the American Museum of Natural History for further study, after which Osborn reached out to Andrews and team via cable, notifying them about the importance of the specimen.

Since Protoceratops fossils are only found in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and this specimen was likely discovered during the Central Asiatic Expeditions, the team concluded that this skull was probably acquired by Delft University between 1940 and 1972 as part of a collection transfer.

[24] As part of the Third Central Asiatic Expedition of 1923, Andrews and team discovered the holotype specimen of Oviraptor in association with some of the first known fossilized dinosaur eggs (nest AMNH 6508), in the Djadokhta Formation.

[13] Gregory M. Erickson and team in 2017 reported an embryo-bearing egg clutch (MPC-D 100/1021) of Protoceratops from the also fossiliferous Ukhaa Tolgod locality, discovered during paleontological expeditions of the American Museum of Natural History and Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

Brown and Schlaikjer discarded the idea of possible skin impressions as this skin-like layer was likely a product of the decay and burial of the individual, making the sediments become highly attached to the skull.

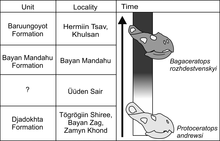

Below are the proposed relationships among Protoceratopsidae by Czepiński:[19] In 2019 Bitnara Kim and colleagues described a relatively well-preserved Bagaceratops skeleton from the Barun Goyot Formation, noting numerous similarities with Protoceratops.

Among scenarios, an anagenetic transition was best supported by Czepiński given the fact that no definitive B. rozhdestvenskyi fossils are found in Udyn Sayr, as expected from a hybridization event; MPC-D 100/551B lacks a well-developed accessory antorbital fenestra (hole behind the nostril openings), a trait expected to be present if B. rozhdestvenskyi had migrated to the area; and many specimens of P. andrewsi recovered at Udyn Sayr already feature a decrease in the presence of primitive premaxillary teeth, hence supporting a growing change in the populations.

Such scenario indicates a possible competition with the more predatory theropods over carcasses, however, as the animal tissue ingestion was occasional and not the bulk of their diet, the energy flow in ecosystems was relatively simple.

Ceratopsians (including protoceratopsids), along with Euoplocephalus, Hungarosaurus, parkosaurid, ornithopod and heterodontosaurine dinosaurs, were found to be in the former category, indicating that Protoceratops and relatives had strong bite forces and relied mostly on its jaws to process food.

They also observed that the maximum or latest stage of development of the neck frill and nasal horn occurred in the oldest Protoceratops individuals, indicating that such traits were ontogenically variable (meaning that they varied with age).

The sampled elements consisted of neck frill, femur, tibia, fibula, ribs, humerus and radius bones, and showed that the histology of Protoceratops remained rather uniform throughout ontogeny.

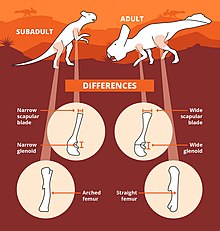

[39] In 2019 however, Słowiak and team described the limb elements of ZPAL Mg D-II/3, which represents a sub-adult individual, and noted a mix of characters typical of bipedal ceratopsians such as a narrow glenoid with scapular blade and an arched femur.

As this behavior would have been common in Protoceratops, it predisposed individuals to become entombed alive during the sudden collapse of their burrows and high energy sand-bearing events—such as sandstorms—and thus explaining the standing in-situ posture of some specimens.

[69] In 2011, during the description of Koreaceratops, Yuong-Nam Lee and colleagues found the above swimming hypotheses hard to prove based on the abundance of Protoceratops in eolian (wind-deposited) sediments that were deposited in prominent arid environments.

[14] Brown and Schlaikjer in 1940 upon their large analysis of Protoceratops noted the potential presence of sexual dimorphism among specimens in P. andrewsi, concluding that this condition could be entirely subjective or represent actual differences between sexes.

Obtained results indicated that other than the nasal horn—which remained as the only skull trait with potential sexual dimorphism—all previously suggested characters to differentiate hyphotetical males from females were more linked to ontogenic changes and intraspecific variation independent of sex, most notably the neck frill.

[78] In 2016, Hone and colleagues analyzed 37 skulls of P. andrewsi, finding that the neck frill of Protoceratops (in both length and width) underwent positive allometry during ontongeny, that is, a faster growth/development of this region than the rest of the animal.

[79] In 2020 nevertheless, Andrew C. Knapp and team conducted morphometric analyses of a large sample of P. andrewsi specimens, primarily confluding that the neck frill of Protoceratops has no indicators or evidence for being sexually dimorphic.

[84] In 2016, Barsbold re-examined the Fighting Dinosaurs specimen and found several anomalies within the Protoceratops individual: both coracoids have small bone fragments indicatives of a breaking of the pectoral girdle; the right forelimb and scapulocoracoid are torn off to the left and backward relative to its torso.

Schmitz and Motani separated ecological and phylogenetic factors and by examining 164 living species and noticed that eye measurements are quite accurate when inferring diurnality, cathemerality, or nocturnality in extinct tetrapods.

In this formation, P. hellenikorhinus is the representative species, and it shared its paleoenvironment with numerous dinosaurs such as dromaeosaurids Linheraptor and Velociraptor osmolskae;[88][89] oviraptorids Machairasaurus and Wulatelong;[56][90] and troodontids Linhevenator, Papiliovenator, and Philovenator.

[100] and its dinosaur paleofauna is composed of alvarezsaurids Kol and Shuvuuia;[105][106] ankylosaurid Minotaurasaurus;[107] birds Apsaravis and Gobipteryx;[108][109] dromaeosaurid Tsaagan;[110] oviraptorids Citipati and Khaan;[111] troodontids Almas and Byronosaurus;[112][113] and a new, unnamed protoceratopsid closely related to Protoceratops.

He also considered it unlikely that these Protoceratops individuals died after burying themselves in the sand given that these specimens are only found in structureless sandstones; an arched posture would pose hard breathing conditions; and burrowers are known to excavate headfirst and sub horizontally.

Fastovsky pointed out these two factors combined indicate that this site was host to high biotic activity, mainly composed of arthropod scavengers who were also involved in the recycling of Protoceratops carcasses.

[120] In 1998 during a conference abstract at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, James I. Kirkland and team reported multiple arthropod pupae casts and borings (tunnels) on a largely articulated Protoceratops specimen from Tugriken Shireh, found in 1997.

The last larvae to emerge would have feed on the dried tendons and cartilage in the joint areas—thereby explaining the notorious poor preservation of these areas in the specimen—and subsequently chewing on the bone itself, prior to pupating.

[14] In 2016 Meguru Takeuchi and team reported numerous fossilized feeding traces preserved on skeletons of Protoceratops from the Bayn Dzak, Tugriken Shireh, and Udyn Sayr localities, and also from other dinosaurs.

[125] The folklorist and historian of science Adrienne Mayor of Stanford University has suggested that the exquisitely preserved fossil skeletons of Protoceratops, Psittacosaurus and other beaked dinosaurs, found by ancient Scythian nomads who mined gold in the Tian Shan and Altai Mountains of Central Asia, may have played a role in the image of the mythical creature known as the griffin.