Prussian Lithuanians

[3] Unlike most Lithuanians, who remained Roman Catholic after the Protestant Reformation, most Lietuvininkai became Lutheran-Protestants (Evangelical-Lutheran).

Almost all Prussian Lithuanians were murdered or expelled after World War II, when East Prussia was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union.

Local self-designating terms found in literature, such as Sziszionißkiai ("people from here"), Burai (German: Bauern), were neither politonyms nor ethnonyms.

The usage of Lietuvininkai is problematic as it is a synonym of the word Lietuviai ("Lithuanians"), and not the name of a separate ethnic sub-group.

For Prussian Lithuanians loyalty to the German state, strong religious beliefs, and the mother tongue were the three main criteria of self-identification.

For example, inhabitants of Lithuania did not trust Prussian Lithuanians in the Klaipėda Region and tended to eliminate them from posts in government institutions.

The area between the rivers Alle and Neman became almost uninhabited during the 13th-century Prussian Crusade and wars between the pagan Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Teutonic Order.

Local tribes were resettled, either voluntarily or by force, in the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Better living conditions in the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights attracted many Lithuanians and Samogitians to settle there.

After 1525, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Albert became duke of Prussia and converted to Protestantism.

Although Lithuanians who settled in Prussia were mainly farmers, in the 16th century there was an influx of educated Protestant immigrants from Lithuania, such as Martynas Mažvydas, Abraomas Kulvietis and Stanislovas Rapolionis, who became among the first professors at Königsberg University, founded in 1544.

[12] To compensate for the loss, King Frederick II of Prussia invited settlers from Salzburg, the Palatinate, and Nassau to repopulate the area.

From the mid-18th century, a majority of Prussian Lithuanians were literate; in comparison, the process was much slower in the Grand Duchy.

[13] The first Prussian Lithuanian elected to the Reichstag, Jonas Smalakys, was a fierce agitator for the integrity of the German Empire.

In 1879, Georg Sauerwein published the poem Lietuwininkais esame mes gime in the newspaper Lietuwißka Ceitunga.

Studying the German language provided the possibility for Prussian Lithuanians to become acquainted with Western European culture and values.

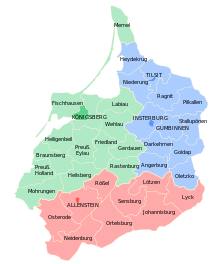

The northern part of East Prussia beyond the Neman River was detached from East Prussia at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, dividing the territories inhabited by Prussian Lithuanians between Weimar Germany and the Klaipėda Region (Memelland) under the administration of the Council of Ambassadors, which was formed to enforce the agreements reached in the Treaty of Versailles.

The organisation "Deutsch-Litauischer Heimatbund" (Lithuanian: Namynês Bundas) sought reunification with Germany or to create an independent state of Memelland and had a membership of 30,000 individuals.

The Prussian Lithuanian newspaper Naujaſis Tilźes Keleiwis was not closed down until 1940, during World War II.

Church services in Tilsit and Ragnit were held in the Lithuanian language until the evacuation of East Prussia in late 1944.

Many refugees perished due to Soviet low-flying strafing attacks on the civilians columns,[19] or the extreme cold.

[19] All who remained at the war's end were expelled from Soviet's Kaliningrad Oblast and from the former Klaipėda Region, which was transferred to the Lithuanian SSR in 1947.

[20] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, some Prussian Lithuanians and their descendants did not regain lost property in the Klaipėda region.

Together with 65,000 refugees from Lithuania proper, mostly Roman Catholic, who made their way to the western occupation zones of Germany, by 1948 they had founded 158 schools in the Lithuanian language.

Many other authors who wrote in Lithuanian were not Prussian Lithuanians, but local Prussian Germans: Michael Märlin, Jakob Quandt, Wilhelm Martinius, Gottfried Ostermeyer, Sigfried Ostermeyer, Daniel Klein, Andrew Krause, Philipp Ruhig, Matttheus Praetorius, Christian Mielcke, Adam Schimmelpfennig, for example.

Prior to World War I, the government and political parties financed the Prussian Lithuanian press.

Attempts to create a unified newspaper and common orthography for all Lithuanian speakers at the beginning of the 20th century were unsuccessful.

Books and newspapers that were published in Lithuania in Roman type were reprinted in Gothic script in Memel Territory in 1923–39.