Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, c. 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus (/ˌɛləˈɡæbələs/ EL-ə-GAB-ə-ləs) and Heliogabalus (/ˌhiːliə-, -lioʊ-/ HEE-lee-ə-, -lee-oh-[3]), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager.

A close relative to the Severan dynasty, he came from a prominent Syrian Arab family in Emesa (Homs), Syria, where he served as the head priest of the sun god Elagabal from a young age.

He brought the cult of Elagabal (including the large baetyl stone that represented the god) to Rome, making it a prominent part of religious life in the city.

According to the accounts of Cassius Dio and the Augusta, he married four women, including a Vestal Virgin, in addition to lavishing favours on male courtiers they suggested to have been his lovers,[7][8] and prostituted himself.

[12] Despite near-universal condemnation of his reign, some scholars write warmly about his religious innovations, including the 6th-century Byzantine chronicler John Malalas, as well as Warwick Ball, a modern historian who described him as "a tragic enigma lost behind centuries of prejudice".

[17][18] Other relatives included Elagabalus's aunt Julia Avita Mamaea and uncle Marcus Julius Gessius Marcianus and their son Severus Alexander.

[30] Herodian writes that when the emperor Macrinus came to power, he suppressed the threat to his reign from the family of his assassinated predecessor, Caracalla, by exiling them—Julia Maesa, her two daughters, and her eldest grandson Elagabalus—to their estate at Emesa in Syria.

[33] The soldiers of the Third Legion Gallica at Raphana, who had enjoyed greater privileges under Caracalla and resented Macrinus (and may have been impressed or bribed by Maesa's wealth), supported this claim.

[42] That month, Elagabalus wrote to the Senate, assuming the imperial titles without waiting for senatorial approval,[46] which violated tradition but was a common practice among third-century emperors.

[67] Under Elagabalus, the gradual devaluation of Roman aurei and denarii continued (with the silver purity of the denarius dropping from 58% to 46.5%),[68] though antoniniani had a higher metal content than under Caracalla.

[75] A lavish temple called the Elagabalium was built on the east face of the Palatine Hill to house Elagabal,[76] who was represented by a black conical meteorite from Emesa.

[77] Dio writes that in order to increase his piety as high priest of Elagabal atop a new Roman pantheon, Elagabalus had himself circumcised and swore to abstain from swine.

[80]The most sacred relics from the Roman religion were transferred from their respective shrines to the Elagabalium, including the emblem of the Great Mother, the fire of Vesta, the Shields of the Salii, and the Palladium, so that no other god could be worshipped except in association with Elagabal.

[88] The emperor reportedly wore makeup and wigs, preferred to be called a lady and not a lord, and supposedly offered vast sums to any physician who could provide him with a vagina by means of incision.

[88][91] Some historians, including the classicists Mary Beard, Zachary Herz, and Martijn Icks, treat these accounts with caution, as sources for Elagabalus' life were often antagonistic towards him and largely untrustworthy.

[92][93] In November 2023, the North Hertfordshire Museum in Hitchin, United Kingdom, announced that Elagabalus would be considered as transgender and hence referred to with female pronouns in its exhibits due to claims that the emperor had said "call me not Lord, for I am a Lady".

[102] In response, members of the Praetorian Guard attacked Elagabalus and his mother: He made an attempt to flee, and would have got away somewhere by being placed in a chest had he not been discovered and slain, at the age of eighteen.

[108] Furthermore, the political climate in the aftermath of Elagabalus's reign, as well as Dio's own position within the government of Severus Alexander, who held him in high esteem and made him consul again, likely influenced the truth of this part of his history for the worse.

[112] Historian Clare Rowan calls Dio's account a mixture of reliable information and "literary exaggeration", noting that Elagabalus's marriages and time as consul are confirmed by numismatic and epigraphic records.

[126] The author of the most scandalous stories in the Historia Augusta concedes that "both these matters and some others which pass belief were, I think, invented by people who wanted to depreciate Heliogabalus to win favour with Alexander".

[13] The Historia Augusta is widely regarded to have been written by a single author who used multiple pseudonyms throughout the work, and has been described as a "fantasist" who invented large parts of his historical accounts.

[127] Gibbon wrote: To confound the order of the season and climate, to sport with the passions and prejudices of his subjects, and to subvert every law of nature and decency, were in the number of his most delicious amusements.

A long train of concubines, and a rapid succession of wives, among whom was a vestal virgin, ravished by force from her sacred asylum, were insufficient to satisfy the impotence of his passions.

The master of the Roman world affected to copy the manners and dress of the female sex, preferring the distaff to the sceptre, and dishonored the principal dignities of the empire by distributing them among his numerous lovers; one of whom was publicly invested with the title and authority of the emperor's, or, as he more properly styled himself, the empress's husband.

Yet, confining ourselves to the public scenes displayed before the Roman people, and attested by grave and contemporary historians, their inexpressible infamy surpasses that of any other age or country.

[128]The 20th-century anthropologist James George Frazer (author of The Golden Bough) took seriously the monotheistic aspirations of the emperor, but also ridiculed him: "The dainty priest of the Sun [was] the most abandoned reprobate who ever sat upon a throne ...

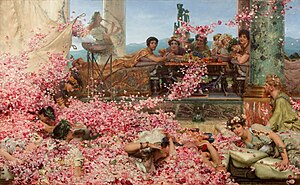

[129] The first book-length biography was The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus[130] (1911) by J. Stuart Hay, "a serious and systematic study"[131] more sympathetic than that of previous historians, which nonetheless stressed the exoticism of Elagabalus, calling his reign one of "enormous wealth and excessive prodigality, luxury and aestheticism, carried to their ultimate extreme, and sensuality in all the refinements of its Eastern habit".

Prado instead suggests Elagabalus was the loser in a power struggle within the imperial family, that the loyalty of the Praetorian Guards was up for sale, and that Julia Maesa had the resources to outmaneuver and outbribe her grandson.

In this version of events, once Elagabalus, his mother, and his immediate circle had been murdered, a campaign of character assassination began, resulting in a grotesque caricature that has persisted to the present day.

Ball describes the emperor's ritual processions as sound political and religious policy, arguing that syncretism of eastern and western deities deserves praise rather than ridicule.

fides exercitus (" the Faith of the Army ")