Psilocybe semilanceata

Psilocybe semilanceata, commonly known as the liberty cap, is a species of fungus which produces the psychoactive compounds psilocybin, psilocin and baeocystin.

The earliest reliable history of P. semilanceata intoxication dates back to 1799 in London, and in the 1960s the mushroom was the first European species confirmed to contain psilocybin.

However, the generally accepted lectotype (a specimen later selected when the original author of a taxon name did not designate a type) of the genus as a whole was Psilocybe montana, which is a non-bluing, non-hallucinogenic species.

[23] On the underside of the mushroom's cap, there are between 15 and 27 individual narrow gills that are moderately crowded together, and they have a narrowly adnexed to almost free attachment to the stipe.

[2] The anamorphic form of P. semilanceata is an asexual stage in the fungus's life cycle involved in the development of mitotic diaspores (conidia).

In culture, grown in a petri dish, the fungus forms a white to pale orange cottony or felt-like mat of mycelia.

[24] Although little is known of the anamorphic stage of P. semilanceata beyond the confines of laboratory culture, in general, the morphology of the asexual structures may be used as classical characters in phylogenetic analyses to help understand the evolutionary relationships between related groups of fungi.

[25] Scottish mycologist Roy Watling described sequestrate (truffle-like) or secotioid versions of P. semilanceata he found growing in association with regular fruit bodies.

P. mexicana, commonly known as the "Mexican liberty cap", is also similar in appearance, but is found in manure-rich soil in subtropical grasslands in Mexico.

[31] Psilocybe semilanceata fruits solitarily or in groups on rich[22][32] and acidic soil,[33][34] typically in grasslands,[35] such as meadows, pastures,[36] or lawns.

[34] P. semilanceata, like all others species of the genus Psilocybe, is a saprobic fungus,[37][38] meaning it obtains nutrients by breaking down organic matter.

[35] Laboratory tests have shown P. semilanceata to suppress the growth of the soil-borne water mold Phytophthora cinnamomi, a virulent plant pathogen that causes the disease root rot.

[41] When grown in dual culture with other saprobic fungi isolated from the rhizosphere of grasses from its habitat, P. semilanceata significantly suppresses their growth.

This antifungal activity, which can be traced at least partly to two phenolic compounds it secretes, helps it compete successfully with other fungal species in the intense competition for nutrients provided by decaying plant matter.

[42] Using standard antimicrobial susceptibility tests, Psilocybe semilanceata was shown to strongly inhibit the growth of the human pathogen methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

[44] In Europe, P. semilanceata has a widespread distribution, and is found in Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Channel Islands, Czech republic, Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey,[45] the United Kingdom and Ukraine.

[46] It is generally agreed that the species is native to Europe; Watling has demonstrated that there exists little difference between specimens collected from Spain and Scotland, at both the morphological and genetic level.

In Canada it has been collected from British Columbia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Quebec.

[50] The first reliably documented report of Psilocybe semilanceata intoxication involved a British family in 1799, who prepared a meal with mushrooms they had picked in London's Green Park.

According to the chemist Augustus Everard Brande, the father and his four children experienced typical symptoms associated with ingestion, including pupil dilation, spontaneous laughter and delirium.

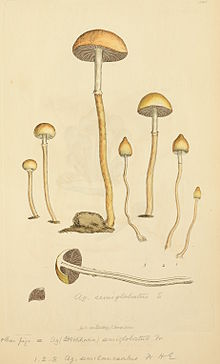

[51] The identification of the species responsible was made possible by James Sowerby's 1803 book Coloured Figures of English Fungi or Mushrooms,[52] which included a description of the fungus, then known as Agaricus glutinosus (originally described by Moses Ashley Curtis in 1780).

"[53] In the early 1960s, the Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann—known for the synthesis of the psychedelic drug LSD—chemically analyzed P. semilanceata fruit bodies collected in Switzerland and France by the botanist Roger Heim.

[67] Michael Beug and Jeremy Bigwood, analyzing specimens from the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, reported psilocybin concentrations ranging from 0.62% to 1.28%, averaging 1.0 ±0.2%.

[68] In a 1996 publication, Paul Stamets defined a "potency rating scale" based on the total content of psychoactive compounds (including psilocybin, psilocin, and baeocystin) in 12 species of Psilocybe mushrooms.

Although there are certain caveats with this technique—such as the erroneous assumption that these compounds contribute equally to psychoactive properties—it serves as a rough comparison of potency between species.

[70] Common side effects of mushroom ingestion include pupil dilation, increased heart rate, unpleasant mood, and overresponsive reflexes.

In one case reported in Poland in 1998, an 18-year-old man developed Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, arrhythmia, and suffered myocardial infarction after ingesting P. semilanceata frequently over the period of a month.

[74] In another instance, a young man developed cardiac abnormalities similar to those seen in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, characterized by a sudden temporary weakening of the myocardium.

Although many European countries remained open to the use and possession of hallucinogenic mushrooms after the US ban, starting in the 2000s (decade) there has been a tightening of laws and enforcements.